When the heavens opened over Fanaye. A rain song meditation.

Moments lost in time, like tears in rain.

Précis

For most of 1974 - 76 I resided in a 10-foot square mud hut with a thatched roof in a small village in the valley of the Senegal River on the edge of the Sahara, where it had not rained for six years. The cattle had all died, the crops had all failed, and we subsisted on emergency food rations from elsewhere in the world. I had been living in Fanaye for nearly two years when the rains finally came back. A three-day rainstorm on Martha’s Vineyard, where I have resided for thirty years, unleashed a cascade of memories of the night the drought broke.1

Summer ends

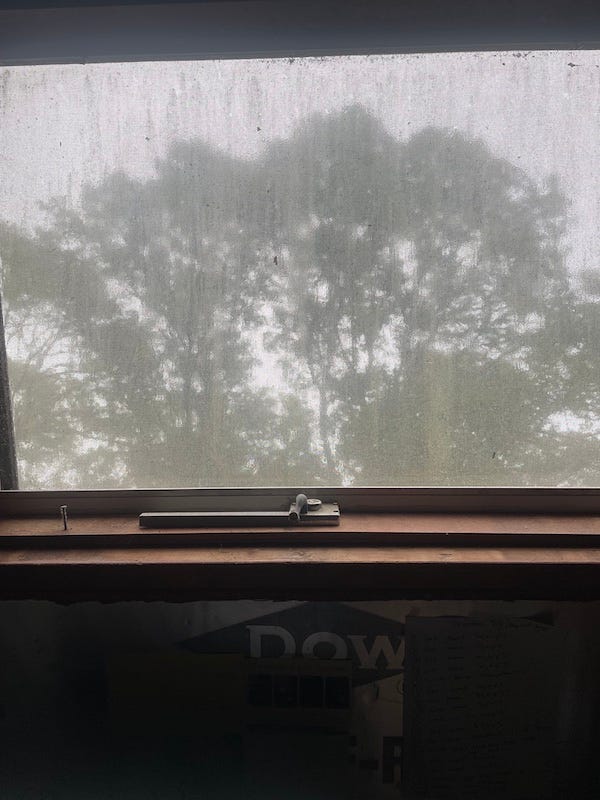

Three mornings ago I took this photo & wrote this caption.

Remnants of a tropical storm in 3rd day here on Martha's Vineyard. I love the sound of rain on the skylight above the desk in my attic office. I haven't turned the lights on; still kind of dark at 8:35 AM on the penultimate day of summer. Wind comes in gusts. Tops of 60' oak trees stop then sway.

I found myself remembering a rainy day long, long ago, when the rains came to Fanaye.

Fanaye Dieri, département de Podor dans la vallée du fleuve Sénégal

For a more in depth description of my time in Fanaye Dieri,2 see the dark side of the hut essay, below — which is the most popular, by far, of the 70 or so posts I’ve so far published on Sundman figures it out!

The dark side of the hut, 50 years later

A little story for you, below, dating from nearly fifty years ago, when I was living in a little mud hut in the village of Fanaye Dieri, Senegal, on the edge of the Sahara desert. But first a little housekeeping.

Here are the paragraphs from that essay that are most relevant to this rain song meditation:

The key thing to keep in mind as you read this story is that it takes place in the context of the great drought, la grande secheresse, which had started about six years before I arrived in Senegal. That region of Africa is known as the Sahel, an Arabic word meaning ‘fringe;’ as it is the southern fringe of the Sahara Desert. So as you would expect, even in non-drought years it is very dry, something like the American Southwest. But during the great drought conditions became even more extreme.

The HalPulaar people were cattle herders, but no cattle remained in Fanaye by the time I arrived there; the only livestock were goats and chickens — and a few horses. Every once in a while people arrived from north by way of camels, so I guess that’s livestock too.

For six years their crops had mostly failed. Had it not been for the emergency food rations from the USA, the EU, France and Saudi Arabia there would have been very little for us to eat. My diet consisted mostly of field corn and sorghum from the US, wheat (made into bread) from the European countries, dates from Saudi — plus some small bony fish from the nearby river, and, once in a while, some goat’s milk. There was also corn-soya-milk, from UNICEF, for the children.

But the drought wasn’t just marked by an absence of rain. The entire ecosystem was simply out of whack. There were plagues of rats that ran in herds like bison on the Great Plains of America before the settlers with guns showed up. Fungi ruined whatever grain one might have managed to store, swarms of locusts came and blotted out the sun, wild boars rooted up any plants that manage to sprout, and mange-mil birds with needle-beaks sucked the juice out of individual grains of sorghum or millet.

Days, weeks, months went by with nothing but clear, hot, blue skies. Then, when what should have been the rainy season came, the clouds appeared. Every day the clouds got a bit thicker. Every day it looked more like a downpour was immanent. At night the winds would pick up. Dust would swirl. There would be thunder and lightning. Oh, it’s going to rain, it’s finally going to rain, at last!

But then, nothing. Not one drop. From time to time I would find myself humming a song I had been taught in second grade:

Oh, It ain't gonna rain no more, no more It ain't gonna rain no more How in the heck can I wash my neck If it ain't gonna rain no more, no more?I remember that that song had deeply scared me until my mother reassured me that it was just a song, and that indeed there would always be rain. Even if it wasn’t raining today, she said, someday soon it would rain again, and we would have water to drink and to take baths and water the gardens. But in Fanaye it wasn’t so easy to believe that the rain would ever come back.

Rain Song, so beautiful, my dear

Any number of songs come into my head when I sit alone and contemplate a heavy rain. Rain, by the Beatles, of course: “when the rain comes, they run and hide their heads. . .” The spiritual Didn’t it rain, “didn’t it rain, rain, didn’t it rain; tell me Noah, didn’t it rain. . .” Led Zeppelin’s cover of When the levee breaks “if it keeps on raining, the levee’s gonna break. . .”

But the song that speaks to me most is the song titled “8” by Sunny Day Real Estate, an ‘emo’ rock band from Seattle. Its intense, surreal lyrics and jarring changes from sweet to overwhelming are the best match for my conflicting emotions:

Rain song So beautiful, my dear Overcome Rain song So beautiful, my dear Overcome Drives me crazy Who can decide? Will I decide? Set in stone to split the night That I bring pain

Among the machubé

From Dark side of the hut:

In Fanaye, most houses were made of adobe. Some had thatched roofs; the larger ones had roofs made of adobe held up by wooden timbers. In anticipation of my arrival, the people of Fanaye had prepared a thatched hut for my residence. It was about 10’ square, with two window openings and a wooden door. Somehow I acquired a small table and a chair. I later hired someone to make a little bookshelf for me. I slept on a mat on the floor. The only other amenity was a terra cotta jug that held a few gallons of water, which was replenished daily with water from a nearby well.

Nobody in Fanaye was wealthy by American standards. Nobody owned a car or had running water or electricity in their homes. Yet many of the older men had worked in France and sent their wages home, they could afford extensively embroidered robes and battery-powered boom boxes; many women wore large earrings of 20-karat gold; one man had even made the hajj, the pilgrimage to Mecca. Before the drought, of course, they had measured their wealth in cattle.

But my hut was among the poorest of the poor of Fanaye, the one family of machubé, which means ‘slaves’. They were not literally enslaved, of course, but they were people who owned only one change of clothes, one pot to cook in, one communal bowl from which to eat. A husband and his pregnant wife.

Although this couple was desperately poor they did own a goat. It was tethered to a stake outside my hut, and like every goat in Fanaye it bleated and farted without stopping, seemingly twenty-four hours every day.

When I lay myself down on my sleeping pad at night I could see stars through the holes in the thatch above my head. I thought of Anne, the woman back in the US that I so desperately missed, and wondered what the hell I was doing there, in my little hut so far away from her. I wondered what would happen to these people — the people of the entire Sahel, spanning nearly four thousand miles from Senegal on the Atlantic coast to Eritrea on the Red Sea; millions of people, “Cowboys” and “Indians,” machubé and millionaires — if the rains never came back, if the Sahara just ate it all, turned everything to desert. I fell asleep worrying about such things to a serenade of goat farts.

Rain melting snow in Somerville

I was introduced to the music of Sunny Day Real Estate sometime around 2002, when I was managing an engineering group at the Kendall Square startup Curl, one of the fifteen or so startups I’ve worked at in my so-called high-tech career. It was spinoff of an MIT project designed to re-engineer the languages used to program distributed applications on the internet, and it was, as I’ve written elsewhere, one of the more fucked companies I’ve had the dubious pleasure to have known.

For two years a rented a room in a house in Somerville that I shared with some guys half my age who were grad students at MIT and Harvard. Every day I rode my bicycle down the hill by way of Prospect Park and Union Square to my office in Technology Square, and up the hill in the evening, stopping by Cambridge Brewing Company en route for a growler of porter, which fit nicely into my backpack. On weekends I went home to Martha’s Vineyard, where my wife and Younger Daughter were. I was lonely in that house. In the evenings I drank porter and hung out on Kuro5hin.

The window of my second floor room looked down on the parking lot of Somerville High. I remember looking out the window one rainy, rainy late-winter morning. There were big piles of slowly melting dirty snow on either side of School Street. I thought about when the rains came to Fanaye. The song 8 was playing in my head.

Put a word to these Put a word to these This thin line greased, I can't see Fingers stain my gold Sweet clover! Sweet clover! Sweet clover! Sweet!

Yasine and Amadou

This is the dedication I gave to my novella Cheap Complex Devices, about which I’ll say more below:

For Yasine Diallo, who drew water from the well for me, and for her son Amadou, who hungered, And for Mamadou Ousmane Tall, who took me in, And for Aïsetta Toomba, the cutest little girl in Fanaye

Yasine was my next door neighbor in Fanaye. On the morning after my first night in my new home — the little mud hut with a thatched roof in need of repair — I went to the well to get water to fill the little terra cotta jug in my room. The women all laughed. I only knew a little Pulaar then, but it was easy to get their message: “Men don’t draw water, silly! That’s a woman’s job.” I laughed and said I didn’t care about that, I would do it anyway, but Yasine insisted that fetching water would be her job for as long as I was her neighbor. And so she filled that little jug, every day.

Yasine was a sweet-tempered woman, kind and gentle with an easy laugh. She had a clubfoot, and walked with a limp. She laughed about that.

A week after Yasine’s son was born, his father butchered the goat, a feast was prepared, the name Amadou was ceremonially bestowed, and the village celebrated.

That night I slept well, not at all missing the goat fart serenade. I was happy for Yasine and her small family.

But it was soon apparent that Amadou was a sickly child. He didn’t nurse well. When I visited my neighbors — all of fifteen feet away — I often sat on a woven mat and held tiny Amadou as his mother pounded sorghum or millet and prepared the family’s meager meals.

I don’t remember the father being there very often. I don’t even remember his name. If he wasn’t working in a field during farming times he was probably off looking for work.

Complex memories in Cambridgeport

After my employment at Curl ended in the spring of 2002 I kept the room on School Street while doing some freelance work, and that summer I finished writing Cheap Complex Devices.

CCD, which presents itself as the report on the inaugural Hofstadter Prize for Machine-Written Narrative, is a actually a metafictiony tale of an entity coming to self-awareness. It’s left for the reader to decide if this entity is a comatose chip-designer with wires coming out of the hole where a bullet entered his brain3, or an APL program running on a malfunctioning floating-point processor, or a brain in a laboratory vat, or a swarm of clover-feasting bees, or a Brigadoon-like Shaker village — or a technical writer with a name very similar to my own who writes documentation for computer hardware and software systems and struggles to reconcile his current high tech life with promises he made to himself decades earlier when he was living in a mud hut in a small African village in the Sahel.

It was hot that summer. My sweltering room in the Somerville house reminded me of the heat of Fanaye.

I knew exactly how I wanted the pages of my book to look, but I didn’t have the ability to create them. My friend Gary, with whom I’d worked at Curl, had skills with the InDesign typesetting tool that I did not have. He offered to help me, just for the fun of it. I rode my bike down Prospect Hill and through Union, Kendall and Central Squares to his place. There, in Gary’s Sahel-hot living room, we sat side by side and together brought Cheap Complex Devices into existence.

Whose side you on? Which side you on? Silence near the battle cry Hollow victory Which lie do you own? Which lie do you own? When lines divide, I walk away Blazing sun sets on my back Sweet clover! Sweet clover! Sweet clover! Sweet!

In the heat of Gary’s room I decided that this little book, into which I had poured my soul, would be dedicated to people I had known nearly thirty years earlier when I lived in a little mud hut on the edge of the Sahara, starting with Yasine and Amadou.

A spiritual experience

Sister Rosetta Tharpe’s proto-rock version of Didn’t it Rain!:

It rained 40 days, 40 nights without stopping

Noah was glad when the rain stopped dropping

Knock at the window, a knock at the door

Crying, ‘Brother Noah can't you take one more?’

Noah cried ‘No, you're full of sin

God got the key and you can't get in’

Just listen how it's rainin'

Will you listen how it's rainin'

Just listen, how it's rainin'

All day, all night

All night, all day

Just listen how it's rainin'

Just listen how it's rainin'

Just listen how it's rainin'

Didn't it rain till dawn?

Rain on. My Lord!

Toxoplasmosis and a tin of powdered skim milk

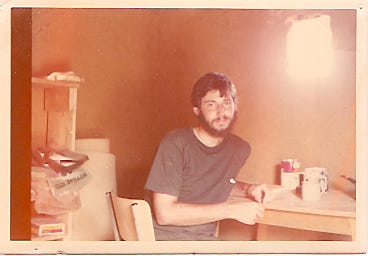

Here’s a photo of a tin that once contained dried skim milk. It sits on my desk under the skylight in my attic office; I keep pens and a pair of scissors in it. I brought it with me when I came home from Africa the first time, a physical and emotional wreck. (If you look in the photo of me in my hut you can see another can that somewhat resembles it.)

When I got my first job as a technical writer at Data General in 1980 I took that tin with me, and it was on my desk when I was working at Mascomp in 1985.

Although you can’t see it in the photo, there’s a dent in the bottom of the tin on the other side. That dent is from when I threw the can full of pens against the wall of my Masscomp cubicle after Betty called to tell me that blood tests indicated that toxoplasmosis, which had been in remission, was now again active in our young son Jakob.4

Hearing my cursing followed by the crash of my pen-can against the wall of the cube, my friend Bob M. came over from the cubicle next to mine and put his arm around my shoulder saying, “John, let’s take a walk.”

Like Amadou, Jakob was a ‘failure to thrive’ baby. That tin I keep on my desk is a reminder of both of them, two tiny, sick, infant boys separated by time, distance, culture, color, so many many things — and yet so very much alike.

My son Jakob is still in a rehabilitation hospital ‘over in America,’ as we Vineyarders sometimes say, getting physical therapy. Lately I’ve been cleaning up Jake’s apartment in anticipation of his return next week. Buried under a pile of dirty clothes I found a little decorative block of wood bearing the words

You can't write the next chapter of your life If you're busy reading the last one

That set me to wondering: is that what I’m doing here in Sundman figures it out! — obsessively rereading the last chapters of my life instead of writing the next? Maybe I should look forward! Maybe I should throw away that Gloria écrémé can!

But somehow I think I won’t.

Didn’t it rain

The rain came before the thunder and lightning did, pouring through the holes in my thatched roof through which I had often gazed up a the stars. But it wasn’t the water that woke me that two AM, it was the choking dust — seven years or more of Saharan dust pounded out of my roof and into my little home. It took me a few seconds to figure out what was happening. At first I had no idea where all the sand and dust came from. All I knew was that I couldn’t breathe.

I got up and ran out the door, and oh, my heavens, you cannot believe how hard it was raining. It could almost knock you over.

I ran back into my hut to see if I could light my kerosene lantern, find some way to cover my books, letters, diary from the rain. But there was no need. The thatch had swelled as it absorbed water, and in a few minute’s time it was as waterproof as the roof under which I now sit in my attic office on Martha’s Vineyard typing these words.

And then the sounds! The thunder, the rain splashing, even the sounds of a mud wall or two collapsing here under torrents onrushing down the narrow pathways of Fanaye, pathways that I now knew so well.

It rained for three solid days, as it did last week here on Martha’s Vineyard. And then it took a break, and then it rained again. Within days the surrounding sandy soil of the dieri, which had looked like a sandbox for the entire time I had lived in Fanaye, was a green sea of thorn-grass.

I remember the sounds of the rain pouring down on my leak-less roof, the muffled sounds of the women pounding the sorghum as they did every day, but now inside rather than out. But the sound I most remember from the day the rains came to Fanaye isn’t the thunder, or the rushing water or collapsing walls. What I remember is the laughter, the laughter and singing of the Fanaye-nabé, of whom I was now one, all of us shouting and dancing and singing in the rain, illuminated only now and then by flashes of lightning.

Epilogue

If you look at the walls behind me in the photo above you’ll see that they are nicely plastered. When I first moved in you could see the individual bricks in the walls, but one day I returned to my place to find Yasine inside, plastering my home, with her bare hands, using the finest red clay that she had carried in a bucket on her head, limping on her deformed foot, from the bank of the little river half a mile away.

“When a person loves your child as you loved mine,” she said, “you want to do something nice for them.”

I was away when Amadou passed away. Omo é Allah, Yasine told me when I arrived home. He is with Allah.

But Jakob is still here, and so am I. Trying to write the next chapter.

Rain song So beautiful, my dear Overcome Rain song So beautiful, my dear Overcome Drives me crazy Who can decide? Will I decide? Set in stone to split the night That I bring pain Rain song So beautiful, my dear Overcome

If you liked this essay you might also like Jerrycans full of gasoline in the back seat, which tells the impossibly melodramatic story of how I first arrived in Senegal, or What's the frequency, Tom?, which describes my disorienting return to the States from Fanaye and my equally disorienting first trip, of an eventual one hundred and twenty, to Silicon Valley, or Entanglement, which describes, among other things, my return to the Senegal River Valley to do research for a master's thesis in agricultural economics two years after I had said goodbye to Fanaye.

"Tears in rain" is a 42-word monologue, consisting of the last words of character Roy Batty in the 1982 Ridley Scott film Blade Runner. Written by David Peoples and altered by Hauer, the monologue is frequently quoted. Wikipedia

Loosely translated from Pulaar: “Sandy-side cowtown”

The chip designer Todd Griffith, who gets shot in the head in the third chapter of my novel Acts of the Apostles.

F-ing excellent.

Just finding this now John. So wonderful. Brings back so many memories. The death of Amadou brought tears to my eyes as I remembered my maid Mariama. She was with me all through her pregnancy. Then one week I had to go to Dakar, and when I got back, I found out that her child had been stillborn. I started to cry and all the women told me to hush and said she would have another.