A chronicler of biodigital technopotheosis

How I accidentally became a self-publishing cyber-bio-nanopunk novelist

If you read my earlier essay Accidental Samurai the post below will seem familiar to you. I revised and slightly expanded that essay, smoothing it a bit and adding in a bit more connective tissue, for

to share to readers of his Doom Fiction substack. He sent it out today, so what the heck I guess I’ll share it with you too. I think this version is considerably better than the earlier one, but it does cover the same territory. Apologies to paid subscribers who are seeing this for the third time, as I accidentally sent out an intermediate draft of this a couple of weeks ago.Précis

In this post I tell the story of how, nearly thirty years ago, I set out to write a simple murder mystery but ended up spending four years creating a whole new imaginary branch of ‘bio-digital’ science just to solve a plot problem.

I’ve now written four novel(la)s, in various styles and formats, and they all deal with two phenomena: (1) the convergence of biological and digital technologies, and (2) hacking. Also, all of my books also seem to make reference in one way or another to religious belief in general and to the Christian mythos in particular.

So ‘biodigital’ is self-explanatory, and ‘technopotheosis’ is just a word I made up by combining ‘technology’ with ‘apotheosis,’ which means to raise something to a God-like status: technology as an object of religious veneration, technology revered as God. Hence ‘biodigital technopotheosis.’

Just as I stumbled, tripped and fell into being a writer of novels that touch in one way or another on biodigital technopotheosis, I also stumbled into being a self-publisher. That story is too long and baroque to be included here, but if you’re interested in such things I recommend my posts The Saga of Acts of the Apostles and Traveling Self-Publishing Novelist Blues: The DEF CON Variations.

Hidden Titanic

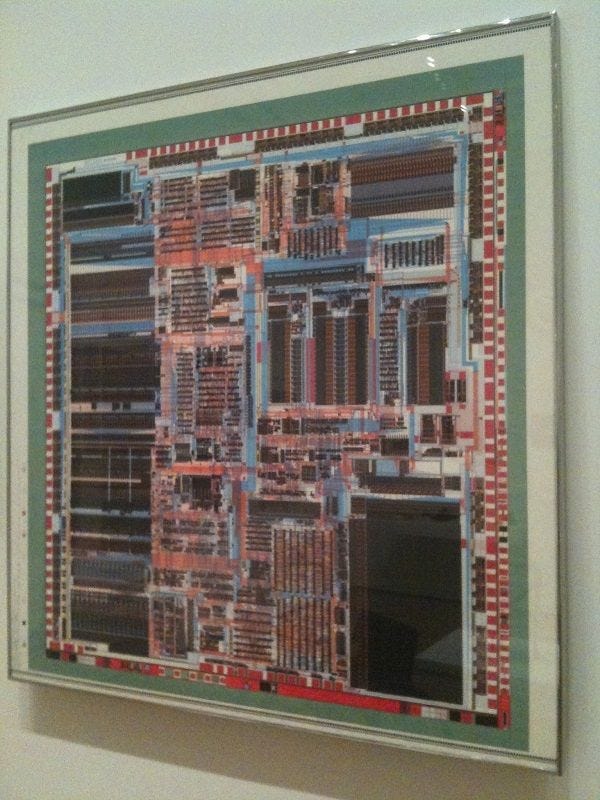

One day in 1988, while walking down a hallway of 2 Federal Street, Billerica, MA, home of the East Coast Division of computer maker Sun Microsystems, I came upon my friend Scott, who was staring intently at something affixed to the wall outside his office. It looked like a very large reproduction of a painting in a modernist, abstract, geometric style, like something you might find in the Metropolitan Museum of Modern Art.

Scott looked somewhat bedraggled and somewhat befuddled. Abstract art has that effect on a lot of people, but what Scott was looking at wasn’t modern art, it was an etch plot of the computer chip he was designing. I knew that he had been wrestling with a tricky bug; it had been driving him nuts for some time. His project was behind schedule and he was under enormous pressure to find and fix the problem. Scott was a very experienced and competent VLSI engineer and he was not used to being in this situation. He was stumped.

At the time I was toying with the idea of writing a murder mystery. I had been a professional writer for nearly ten years by then, but I wrote manuals that explained how computers and operating systems worked, not novels. I had never attempted fiction.

I asked Scott, “I know how to put a trojan horse in software. Could somebody design a trojan horse into that circuitry and you not know about it?”

Scott turned to me and said, “John, there’s two hundred and seventy-five thousand transistors on that chip. You could put the fucking Titanic in there without me knowing about it.”

So, just like that, I had found the premise for my murder mystery: A chip designer — call him ‘Todd’ — discovers that his co-worker has secretly designed a trojan horse into the logic of a chip that they’re working on together. Todd reports this discovery to his boss, and that very night Todd gets a bullet in the head. So, who shot Todd, and why? What was the purpose of that trojan horse?

I filed that idea in the back of my mind and went about my business of writing computer manuals. In 1995 I finally decided to write that murder mystery. The early chapters came very easily, but soon enough I had to deal with a nagging question that had been there from the very start: Why would anybody go to all the trouble of putting a trojan horse into the silicon circuitry of a computer chip when it is so much simpler to do it in software?

It was as if the bad guys, whoever they were, had devised an ingenious plan to break into somebody’s house by going down the chimney like Santa Claus when they already had the key to the front door. Why would they do that? It just didn’t make sense. I reached a point where I had to either figure out why someone had hidden a virtual CPU inside another CPU, or I had to give up on the book. I had written myself into a corner.

By the time I emerged from that corner, after four solid years of work, my book was no longer the simple murder mystery I had naively set out to write.

It was a thriller about hardware hacking and genetic engineering and mind control and brain-re-arranging nanobots and techno-paranoid cyber-militias and Gulf War Syndrome and what-all else. It was about a man who dreamt of becoming God, and the cult of followers who tried to make his dream a reality. It was about the convergence of biological and digital technologies, and hubris, and the postulate of Ted Kaczinsky, the so-called Unabomber, that freedom and technology cannot be reconciled.

I gave my book a title to suggest the religious fervor of Silicon Valley’s belief in technology, with also a hint of apocalypse: Acts of the Apostles.

That book came out twenty-three years ago. It turned out to be pretty prescient in a lot of ways, and has since become a minor cult classic among hackers and geeks of both cyber and bio flavors. I’m preparing a new edition to be released this spring, with a retrospective introduction by Cory Doctorow.

The existential meaning of hacking

My own background is more on the digital side of things than the biological, but I married molecular geneticist and I was, and am, amazed by everything she did in her various laboratories. Starting within days after I met this woman I made a hobby of studying molecular biology from the point of view of a fascinated ignoramus. Because you can damn well believe I was fascinated.

With my sterling background of one undergraduate survey course in biology — taken six years before I met the molecular geneticist in question — I began attending advanced lectures on topics like shifted reading frames and overlapping gene products in single-stranded DNA bacteriophage (viruses that prey on bacteria). I was in way over my head and only understood half of what I heard or read, but yet I did over time manage to learn a lot. And the more I learned, the more I came to think of biology in terms of systems — cells as systems, microbes as systems, organelles as systems, complex organisms like people as systems. . . The more I learned about biological systems, the more I saw similarities between them and the digital systems I was more used to working with. Which made me think of hackers.

Hackers look at complex systems as challenges; they are things to be broken into and manipulated for personal gain, or for political reasons, or to fix things that are broken, or for bragging rights, or, perhaps mainly, for fun; which is to say, hackers hack in order to learn how systems work and to manipulate those systems — just as any healthy 10 month old child delights in manipulating a simple toy. By playing, the child learns — about the toy, about their bodies, about their world, and about the pure joy of control. Many hackers hack for the same simple reason: it’s fun.

The Soul of a New Machine, a nonfiction book by Tracy Kidder, conveyed to general readers some of the joy of designing computer systems. In books like Snow Crash and Neuromancer, Neal Stephenson and William Gibson, among others, created a new genre of science fiction that came to be called ‘cyberpunk,’ that was about the joy of hacking those systems. Breaking into them. Taking control of them.

About the same time as Snowcrash and Neuromancer, although at first not quite as noticed, another new subgenre of science fiction was emerging: biopunk.

If ‘cyberpunk’ is the genre that looks at digital systems from a hacker's point of view, then ‘biopunk’ looks at biological systems from a hacker's point of view.

Most non-biohacker/biopunk people make a distinction between, for example, living, carbon-based biological systems on one hand and silicon-based digital systems on the other. Biopunks don't make that distinction. A system is just a system, and the only question is, how do you hack it?

Now if the system is, for example, you — your brain, your mind, your essence, your soul — you may like it just fine the way it is, thank you very much, and you may not want somebody else (where "somebody" might be “the government” or some squicky corporation) to hack it. So your challenge becomes, How do I define who I am? How do I maintain the integrity of my system?

All my novels deal with themes like these. In Acts of the Apostles1, among other things, I imagined nanomachines analogous to bacteriophage that manipulate DNA and rearrange brains (and by rearranging brains, thus minds, and selves). In a lot of ways in Acts of the Apostles I anticipated CRISPR, the powerful new way of programming DNA that emerged about a decade ago. The plot of my novel revolves around how such a mechanism might work on the molecular level, and invites readers to ponder the ethical considerations that come with it.

Anticipating ChatGPT

In 2002 I published a novella, Cheap Complex Devices, that purports to be about a storytelling contest between two artificial intelligence constructs. Twenty-plus years later, with programs like ChatGPT able to create stories from simple prompts — and even to essentially function as co-authors of novel-length books — I’m amazed to look back at how well I imagined this kind of thing might play out.

Cheap Complex Devices anticipated many of the the questions that human-like storytelling machines would raise and the feelings they would provoke. I find it kind of kind of eerie, actually. Plus, I think Cheap Complex Devices is both one of the funniest and one of the most profound books anybody has ever written. But that’s probably just me.

In Cheap Complex Devices, it's never clear who the storyteller is — it might be Todd, the guy who got a bullet in the head in Acts of the Apostles, or perhaps it’s another person (one who resembles me, maybe?). It might be a computer program that’s telling this story about storytelling computer programs, or it might be a brain in a vat or even a swarm of bees. Read it yourself and form your own conclusions.

A prophetic illustrated dystopian phantasmagoria

If I’m a little freaked out by how well Acts of the Apostles and Cheap Complex Devices predicted certain things ten or twenty years before they happened, my next book, The Pains, which I wrote and published in 2008, gives me the screaming heebie-jeebies.

The Pains is about an imaginary place, which I called ‘Freemerica,’ in which neo-fascist thugs join forces with pan-surveillant transnational corporations, transhumanist tech-bros, and fundamentalist theocrats in an all-out assault on science, freedom of speech, freedom of thought, and basic human decency. If this doesn’t remind you of anything going on in 2024 then I can state with great confidence that you and I don’t perceive current events in the same way. At all.

At the center of The Pains — an illustrated dystopian phantasmagoria that melds two “1984”s: George Orwell’s and Ronald Reagan’s — there is a mysterious laboratory of frozen heads which are probed and manipulated with interesting and unexpected results. In this book you will find biodigital technopotheosis on steroids. If this book doesn’t give you nightmares I’ll give you a refund.

Coda

All meaningful literature examines the human condition with some seriousness of purpose, and I aspire to write meaningful literature. Therefore, I hope, my books reward attentive reading. (But of course it’s not for me to say whether my books do or don’t meet the lofty goals I’ve set for them. You get to decide that for yourself.)

As one of the epigraphs to both Acts of the Apostles and Cheap Complex Devices, I chose these words from Ted Kaczynski’s notorious document “Industrial Society and Its Future,” otherwise known as the Unibomber Manifesto:

Thus it is clear that the human race has at best a very limited capacity for solving even straightforward social problems. How then is it going to solve the far more difficult and subtle problem of reconciling freedom with technology? Technology presents clear-cut material advantages, whereas freedom is an abstraction that means different things to different people, and its loss is easily obscured by propaganda and fancy talk.

The second epigraph to both books comes from the legendary, unbelievably prescient essay by Vannevar Bush called “As we may think”:

We have reached an age of cheap complex devices of great reliability; and something is bound to come of it.

I don't find it possible to write about the human condition without at least some acknowledgment that we are, in some ways, systems. We're chemical systems, we're biological systems, we're logical systems, we’re social systems. And these systems — by which I mean, us — are (as Kaczynski foretold) are increasingly susceptible to manipulation, control, and —who knows? — annihilation — by the very technology that we humans have created, and, in so many cases, revere.

Please join me. My substack is

My novel Biodigital is kind of Acts of the Apostles, reimagined. To keep this essay to a somewhat reasonable length, I don’t discuss it further here.

Did real life Scott ever find the bug? Did he enjoy the book?

“I think she’s trying to save it,” I heard outside my door, waking from a dream of touring a laboratory where giant paper mache heads in a tank teetered between sinking and floating. ... That was the first moment I felt the “How do I define who I am? How do I maintain the integrity of my system?” described here. Then, I was passed out on the floor in front of a giant canvas while in an artist residence. Now, I find myself feeling a different variation of the time, looking into a fortress of tolerance for what I’ve preserved.