The dark side of the hut, 50 years later

The unexpected is unexpected even when you least expect it

Welcome and précis

Sundman figures it out! is an ongoing autobiographical meditation. Incidents, themes, preoccupations and hobbyhorses arise, fade, reappear and ramify. So the more of these essays you read, the more enjoyment you’re likely to get out of subsequent ones.

I sometimes go back and make small edits to the first version of posts that go out to subscribers as emails. I do this to correct typos, add a clarification or links to other related essays. But I try to keep the original post mostly intact. For instance in this post I’ve deleted the introductory parargaph about new editions of my books that was in the email version.

This post tells the story of a short trip to the most remote place I’ve ever been, and the astounding thing I found there.

Unexplored Territory

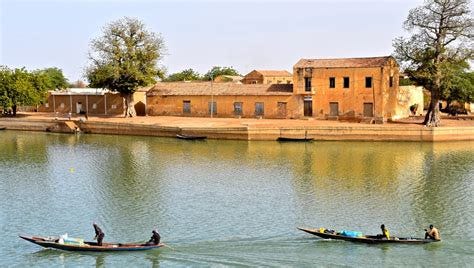

As a Peace Corps Volunteer assigned to a rural development program I was posted to Fanaye Diery (‘fah-nigh jeery’), a HalPulaar village of about 500 people in the Senegal River valley, arriving there in late spring, 1974. (The HalPulaar people take their name from their language: HalPulaar means ‘Pulaar speaker’.)

In Fanaye, most houses were made of adobe. Some had thatched roofs; the larger ones had roofs made of adobe held up by wooden timbers. In anticipation of my arrival, the people of Fanaye had prepared a thatched hut for my residence. It was about 10’ square, with two window openings and a wooden door. Somehow I acquired a small table and a chair. I later hired someone to make a little bookshelf for me. I slept on a mat on the floor. The only other amenity was a terra cotta jug that held about a gallon of water, which was replenished daily with water from a nearby well.

A little distance way, sheltered by the walls of a roofless abandoned building, was the concrete-lidded latrine I hired someone to dig for me as my first order of business.

There was no electricity in Fanaye, nor running water. The nearest post office was in Podor, which could take most of a day to get to, depending on the vagaries of travel. I had a post office box in Podor; letters took about two weeks to get there from the US. That post office was my link to my life back home in America.

Every once in a while — Fourth of July, Thanksgiving, random business — I’d get together with other Americans, either in St. Louis (also called N’Darr), a small city three hours distant from Fanaye by car, with a kind of New Orleans look, near the place where the Senegal River enters the Atlantic Ocean, or, more rarely, in Dakar, Senegal’s capital city (10 hours distant under optimal conditions). But for most of the time over more than a year and a half I resided in Fanaye. I liked it there. I liked it a lot.

The drought

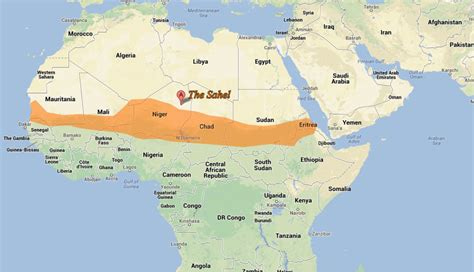

The key thing to keep in mind as you read this story is that it takes place in the context of the great drought, la grande secheresse, which had started about six years before I arrived in Senegal. That region of Africa is known as the Sahel, an Arabic word meaning ‘fringe;’ as it is the southern fringe of the Sahara Desert. So as you would expect, even in non-drought years it is very dry, something like the American Southwest. But during the great drought conditions became even more extreme.

The HalPulaar people were cattle herders, but no cattle remained in Fanaye by the time I arrived there; the only livestock were goats and chickens — and a few horses. Every once in a while people arrived from north by way of camels, so I guess that’s livestock too.

For six years their crops had mostly failed. Had it not been for the emergency food rations from the USA, the EU, France and Saudi Arabia there would have been very little for us to eat. My diet consisted mostly of field corn and sorghum from the US, wheat (made into bread) from the European countries, dates from Saudi — plus some small bony fish from the nearby river, and, once in a while, some goat’s milk. There was also corn-soya-milk, from UNICEF, for the children.

But the drought wasn’t just marked by an absence of rain. The entire ecosystem was simply out of whack. There were plagues of rats that ran in herds like bison on the Great Plains of America before the settlers with guns showed up. Fungi ruined whatever grain one might have managed to store, swarms of locusts came and blotted out the sun, wild boars rooted up any plants that manage to sprout, and mange-mil birds with needle-beaks sucked the juice out of individual grains of sorghum or millet.

Days, weeks, months went by with nothing but clear, hot, blue skies. Then, when what should have been the rainy season came, the clouds appeared. Every day the clouds got a bit thicker. Every day it looked more like a downpour was immanent. At night the winds would pick up. Dust would swirl. There would be thunder and lightning. Oh, it’s going to rain, it’s finally going to rain, at last!

But then, nothing. Not one drop. From time to time I would find myself humming a song I had been taught in second grade:

Oh, It ain't gonna rain no more, no more It ain't gonna rain no more How in the heck can I wash my neck If it ain't gonna rain no more, no more?

I remember that that song had deeply scared me until my mother reassured me that it was just a song, and that indeed there would always be rain. Even if it wasn’t raining today, she said, someday soon it would rain again, and we would have water to drink and to take baths and water the gardens. But in Fanaye it wasn’t so easy to believe that the rain would ever come back.

Rural animation

I was part of a program of the government of Senegal called ‘Animation Rurale,’ which was intended to connect people in the remoter areas with available government services. In this way we were kind of like county agricultural extension agents in the USA. (If you didn’t grow up on a farm or study agriculture at a land-bank university like I did, you can be forgiven for not knowing that ‘county agents’ are still very much a thing.)

In Senegal, the U.S. embassy had a so-called ‘self-help’ fund that we Peace Corps animateurs could use. If the local people provided labor, the U.S. would provide money for locally-initiated improvements.

After the 2 months or so of language, cultural awareness, and similar training in Dakar, my assignment was basically this: Go to Fanaye, get to know the people there, become fluent in the language, help improve the connection between the local people and the regional government services, and ask the people what kind of project they would like help to undertake with money from the self-help fund.

(Of the 110 or so Peace Corps Volunteers in Senegal at that time, about 80 were teachers in high schools which were located in cities or larger towns; many PCVs taught English. Only about 30 of us were animateurs, living in smaller, remoter villages.)

In Fanaye, there was an elementary school teacher paid and managed by the national government, teaching the national elementary school curriculum. But there was no school building; the children sat on the sand for their lessons under a thatch roof. The project the people wanted me to help them with, they told me after I had been living among them for a few months and was no longer a stranger, was a school. If the United States would provide money for cement and roofing materials and tabes and chairs and some blackboards, they would build the building. So, over the next year and a half, that’s what I helped them do. But that’s another story.

Languages and dreams and living without a mirror

In Senegal, French is the official language of government and Wolof is the lingua franca of the people. During in-country training in Dakar before being sent to our posts, most PCVs were taught Wolof and French. But since I was deemed fluent in French I was taught Wolof and Pulaar.

In Fanaye, many of the older men spoke a bit of French, which they had picked up either while serving in the French army, or while working in France as busboys, street cleaners, construction laborers or the like. (This was a great asset to me in learning Pulaar.) All of the men, and a smaller portion of the women, were fluent in Wolof, or nearly so. Government employees — such as the school teacher, nurse at a local clinic, worker at a local agricultural experiment station — all knew French. There was even a veterinarian there for a while, although he had absolutely nothing to do. These civil servants were from different parts of the country, from various ethnic groups, and when they got together they spoke Wolof with each other. Except when I was there, in which case they switched French as a courtesy to me. But the villagers, among each other spoke Pulaar.

I learned to get by in Wolof, but over time I became much stronger in Pulaar. At some point I even began dreaming in Pulaar. I remember waking up one morning and realizing that my mother and my sister Maureen had been in my dream. Only, in my dream they were Black and spoke Pulaar. I didn’t have a mirror in Fanaye, and on those occasions when I got out of the village and visited friends in places like Dakar or St. Louis and saw myself in a mirror it was always kind of a shock to be reminded how white I was.

Dieri and Oualo

The words dieri and oualo (‘jeery’ and ‘wallo’) refer to two kinds of soil and the two kinds of agriculture that go with them. Dieri soils are sandy and rely on rain (or irrigation) to grow crops. Oualo soils are clayey; they form the flood plain of the Senegal River. After the annual flood recedes, oualo soil forms a hard crust that prevents water from evaporating. This soil can support crops that grow for months without being watered.

During the drought the floods still came to Fanaye because the headwaters were a thousand miles to the south, in hills and jungles where the rains had not stopped. In normal times, when there was rain, the farmers of Fanaye would grow millet and squash and melons in the dieri soil. But during the drought none of that grew. In the oualo they grew sorghum and beans. When I was there, most of those crops that grew in the oualo were destroyed by the pests I mentioned earlier — locusts, fungi, birds, rats. Even wild boars.

In a satellite view you can tell oualo from dieri which at a glance. The dieri, on the bottom half of the picture, looks like a sandbox — which it basically is. In the green oualo, you can see the winding Senegal River and a few of its smaller offshoots.

Cowboys and Indians

Fanaye was an established place with a long history. The people were muslims; they prayed five times each day, and every evening the older men went to the mosque, which was a hundred years old, and sat in a circle and chanted la ilaha illa Allah for nearly an hour.

In that region of the country there were also people usually known as Peuhls (a Wolof name for the Fula people). HalPulaar people (as I understand this, I’m no expert) are closely related to the Fula — indeed Pulaar is a dialect of the Fula language, which known as Fulani — but they are distinct peoples.

When I was living in Senegal, every Peuhl person I met was a nomad. Sometimes several of them would pass through Fanaye with their flock of goats — arriving from one direction, leaving in another. They had a reputation among local people in Fanaye for being taciturn and desert-hardened. They lived by their own rules and didn’t want anything to do with officialdom, it was said. I did have a few conversations with Peuhl people passing through, but they weren’t especially friendly, as I recall. And clearly the languages we spoke were different, even if mutually intelligible. Perhaps something like Swedish and Norwegian?

And I have a funny story (for another time) about how one Peuhl fellow expressed to me what he thought about religious piety. Short version: not much. My point is that even as Fanaye came to me to feel more and more like home, the life led by the Peuhl people seemed a bit mysterious and exotic to me.

So one day I asked my friend the school teacher about the relationship between these two groups — the sedentary HalPulaar farmers and the nomadic Peulh shepherds. He replied using English words — the only time I ever heard him do so — “Nous sommes les cowboys,” he said. “lls sont les Indians.” We’re the cowboys. They’re the Indians.

Well well well

As the drought wore on, people in the government and in relief agencies began to worry that a humanitarian crisis was looming. To date they had been able to prevent famine with the help of food donated from abroad. But what about water? Even in the interior, far away from the river, there were wells. But the here and there wells were going dry as the water table sank. With no water in the wells, people would be forced to leave. But where would they go? The specter of refugee camps was starting to take shape, and it was frightening.

In Dakar, the US and Senegal came up with a plan: The United States would put up the money, and the government of Senegal, with the help of Peace Corps Volunteers, would identify places that needed wells to be deepened or new wells dug. (I have a funny story about how we put together the budget for this project, but this post is already much too long, so that story can wait.)

So the next problem was: where should we put these wells?

It was easy enough to identify well targets in established places like Fanaye, but how would we find the right places to put wells that would help the Peulhs? They were largely disconnected from the government. They kept to themselves. There were no roads in the deep parts of the dieri where they grazed their goats (and their cows, presumably, before la secheresse killed most of them). The maps we had were all provisional. If a map indicated that a village was at place X, that only meant that it was there when the map had been made. These people moved around. Who knew if that village was still there today.

This unmapped, roadless interior was called by some of my Senegalese colleagues, le bled.

By donkey cart into the void

And so it came to pass that I found myself on a donkey cart with a Senegalese official — I’ll never remember what his title was; he was just a worker bee like me — and a map, and a compass, and a lot of water, and a guide who swore he knew where he was going. I sure hoped he knew where he was going, because if we got lost, heaven help us. And thus we set off to find this rumored village, somewhere out there in that vast emptiness south of Fanaye, that might need a well. I felt as I suppose Col. Percy Harrison Fawcett might have felt as he set off into the Amazon jungle in search of the Lost City of Z.

But indeed, after about 3 hours we arrived at the village we had been looking for. Children ran out to see us crying toubab! toubab! (I was probably the first white person any of them had seen). It was a small encampment, the buildings there were all made of branches from local scrub brush, covered, I seem to recall, with goat hides. I want to say there were about 30 people, but I really don’t remember. There were goats and even some emaciated cattle. And a single, forlorn, unlined well.

When the reason for our visit was made clear — that we wanted to give them a new, deep, cement-lined well, and we just wanted to know where they were and if that was OK with them — there was much rejoicing, and I, in particular, was treated as royalty.

After a bit of back and forth I gave into their strong request that I accept the honor of sitting in the finest hut the village had to offer. Now, this was the last thing I wanted to do — to go sit, by myself, in a hot hut, while the people, the discussion, the sights and sounds were just outside. But it became clear that it would be rude of me to refuse. And then they brought in something unspeakable precious for me to drink: fresh cow’s milk, sweetened with a bit of rock sugar.

You have to understand that I had scrupulously avoided drinking any raw milk for a year and a half because there was tuberculosis in Senegal and you could catch it, we were instructed in our training, from drinking raw milk. But I said to myself, “oh well,” and I drank it, as some of my new friends peered at me through the door, waiting to see my reaction. And indeed was indeed refreshing, and I was able to tell them so in their language, which delighted them.

And then, and then and then. You’re not going to believe this, but I swear on all things holy, that this is what happened next.

Surely some great revelation is at hand

And then a young man appeared, and he set before me, on the sandy floor of that hut, a battery powered record player. And he produced a cardboard sleeve that contained a vinyl record, which he proceeded to withdraw from the sleeve. And not just any sleeve. It was a black sleeve on which there was the image of a prism splitting a narrow beam of light into its constituent colors.

And then, in my honor, he turned on the record player and played that record, a record which I had never heard played before that moment, a recored which celebrates its 50th anniversary this year.

I have nothing more to add to this story, other than I hope that you have experienced, or someday will experience, something as glorious as I experienced that day.

Postscript

This post generated a comment or two about how hearing the music of Dark Side of the Moon must have affected me. I tried to clarify:

Yes, that was the first time I heard that album, and no, I don't remember a thing about the experience of the music. What I do remember is being so completely astounded at what I was experiencing — the extraordinary generosity in the welcome I was being given by some of the, literally, materially poorest people on Earth; the disconnect between my prior assumptions about what I would find and what I actually did find; and the astounding fact that the music of an avant-guarde British rock group would be the seal on the connection between me and the people of that obscure village of African nomads. That's what I was trying to convey. The music itself, for all its indisputable grandeur, is almost incidental to the story.

If you liked this story you may enjoy a few of my other essays that relate to it in one way or another.

In When the heavens opened over Fanaye: A rain song meditation, I share stores of other experiences I had during my two years in Fanaye Dieri, and after — things that were, in many ways, even more profound than what I wrote about here.

Jerrycans full of gasoline in the back seat (parts 1 & 2) tells about some things I experienced in the months just before I went to Africa for the first time; things that were, in their own way, just as astonishing as what happened on that trip south from Fanaye. In What’s the frequency, Tom? I try to describe the shock I experienced upon returning to the US after 2 years in Senegal, bone-weary and emaciated, and finding it so full of well-fed white people — and the disorientation I felt a decade later, when my long, complicated love/hate affair with Silicon Valley began. And the essay Entanglement describes, among other things, my return to the Senegal River Valley to do research for a master's thesis in agricultural economics two years after I had said goodbye to Fanaye.

The most memorable scene in the middle Indiana Jones movie is when Kate Capshaw is repulsed by the villagers' food offering, and Indy tells her "some of these people haven't eaten in days. You are insulting them and embarrassing me. Eat."

I thought those 10 seconds were some of the clearest, simplest moral instruction ever put on film.

Truly enjoyed Dark Side of the Hut, and great closer!

Had a similar epiphany (epiphony?) in 1976. After a late afternoon of tossing frisbees on Red Square to an curious crowd, and sometimes slowing/stopping traffic, several of my buds and I were invited to ‘our place for drinks and getting to know you’ by a similarly student-aged group who had become friendly in the course of the frisbee diplomacy repartee.

We said ‘yeah’ or something equivalent - it was thirsty work.

They had or found a ride, I think, but may well have been public transport.

And during the ensuing evening numbers of their friends squeezed in and out of a cozy dorm like space until the wee hours, sharing beer and vodka and schnapps and cigarettes while we worked on our primitive Russian, and they their English, German, French or whatever lingua was common currency in the moment. Belts were exchanged, hats, shirts, blue jeans, paper money, spare passport photos, all to the tune of their one English record, played over and over: it was MY baptism in Led Zeppelin IV & Stairway to Heaven...!

We finally realized people were trying to sleep all around us, so we stumbled out of the army barracks into the quiet dark of wee hours Moscow and made our way (these were the days of Cyrillic maps on paper!) back to our hotel.

Still listening, 47 years later. Loved the recent tribute by Heart: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uUB8kBKAFcg