Jerrycans full of gasoline in the back seat (1)

The most intense three hours of my life so far, part one of two parts

Précis

Fifty years and and five days ago, on February 23, 1974, in a region of upstate New York encompassing the Village of Clinton and the City of New Hartford (virtually a part of Utica), over a period of about three hours, the universe collapsed upon me and my friend Anne.

It collapsed upon us with a force equivalent to that of two neutron stars colliding. Somewhere in the universe whole earth-masses of gold and platinum were created as a result.

Indeed, the events which I will attempt to describe in this Sundman figures it out! essay were so extreme that they not only set the trajectory of my life from that point forward, they warped spacetime itself — a claim, which, alas, this format does not allow me to substantiate, although I hope that the story on its own will convince you of the plausibility of my assertion.

A proper account of the spectacular events of that crowded hour requires some context. Therefore I provide some background on topics including: gasoline rationing in the mid 1970’s; communications technology in the USA at that time; S&H Green Stamps; my living arrangements in February 1974; and the nature of the relationship between Anne and myself before and after the cosmic event at the heart of this story. Pretty much everything I talk about in this essay takes place between October, 1973 and June 1974, although there are premonitions and aftershocks that appear on either side of those dates.

Jerry cans full of gasoline in the back seat is populated by absurd coincidences and crackpot New Age notions like astral communication and the transmigration of souls, things in which I do not believe but which seemed to keep happening in my vicinity at that time, when the universe was in flux. This story contains at least 6 separate components, any single one of which would be hard to believe, and which when taken together amount to cosmic farce.

Yet the heart of this story is the unambiguously true account of how Anne saved my life with an act of mind-boggling courage while her own life-death status was manifestly unclear.

This is a hard story to tell. I mean technically, not emotionally. The outline is simplicity itself: Boy & Girl meet, share an intense few months during which, due to a previously undiagnosed condition, Girl nearly dies, twice. Boy & Girl pledge each other eternal love. Girl gets better. Boy departs. The end.

That’s the outline; it’s not the essence, which is something terrifying, beautiful and cosmically funny.

I don’t know if I can convey that essence or if it’s even worth trying. In fact I have a feeling that this essay about one of the most significant events of my entire life is just going to sound to you like the plot of a few episodes a silly 1970’s soap opera — All My Children, perhaps — which Anne used to watch with her dormitory suite-mates, crowded around a tiny black and white television.

Oh what the hell. Sundman figures it out! is about figuring it out, whatever ‘it’ is, so I’m going to give it a shot. Like all my squirrel-brain stories it hops around a bit both topically and chronologically. I place things in the order that makes sense to me. Just look at the dates & you can sort out the linear order if you feel like it.

With this précis having been given, let us proceed.

Soundtrack

The Rolling Stones recorded this song at a studio in Germany in April and May of 1974, a period when the cosmic aftershocks of the jerrycans in Utica were still particularly pronounced throughout our part of the Milky Way; no doubt those aftershocks were felt by Mick Taylor, Keith Richards and Nicky Hopkins & pals as they wove this aural tapestry. I suggest listening to Time waits for no one at least once as you read this post, as it encapsulates a benefaction of significance. Tick, tock; tick tock.

Yes, star crossed in pleasure the stream flows on by As we're sated in leisure, we watch it fly And time waits for no one, and it won't wait for me Time waits for no one, and it won't wait for me

A package at a post office in Dakar

On the morning of April 16, 1974, after four days of preliminaries in Washington, D.C. I arrived in Dakar, the capital of the west African country Senegal, to begin two months of Peace Corps training before beginning my assignment as a rural/agricultural development agent based in the small village of Fanaye Dieri in the Senegal River valley, two day’s travel from Dakar.

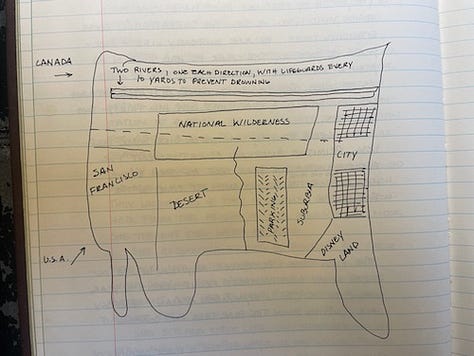

Peace Corps in Senegal had a policy of sending trainees like me (who would be living alone, far from running water, electricity, or any other Americans), within a week of our arrival in-country, for a four-day visit to the places where we would be living for the next for the next two years. This technique had the effect of flushing out those people who were not suited to the task at hand before Peace Corps had invested too much time and money in their training.

The ‘drop-’em-off-and-see-how-they-like-it’ policy worked. Immediately upon completing their first overnight stay in the outback, a few people in my training cohort quit the Peace Corps and went back to the States. But I loved my first four days living in a small remote African village and I couldn’t wait to finish my training & get sworn in as a PCV. Since I already knew French, the official language of Senegal, I spent the two months upon my return to Dakar learning to speak Wolof and Pulaar.

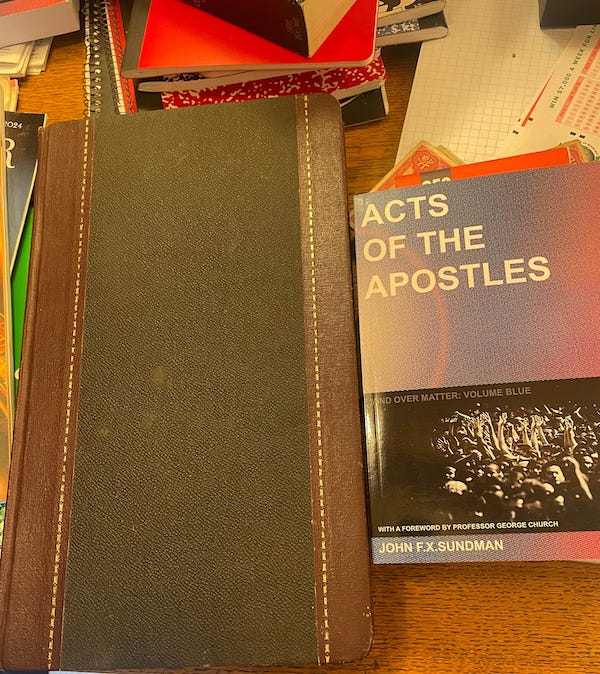

While still in Dakar, about six weeks into my training, I got a notice that a package awaited me at a nearby post office. I made my way there, and, after paying a small customs fee and ignoring hints that I pay a bribe, I got the mysterious item. Back at training, I opened it.

On the inside cover of the book, written in Anne’s distinctive hand, are these words, which have been attributed to the 16th century English poet Ben Johnson:

To the Reader: Pray thee, take care, that tak'st my book in hand To read it well: that is, to understand

My Bloody Valentine

On February 14, 1974, Anne, who had complained of stomach pain for months to the doctor at the campus health center but had not received a diagnosis, vomited a significant amount of blood in a women’s room in the Hamilton College gym. She collapsed but managed to crawl to a hallway, covered in blood, where she passed out. She was discovered by a teacher and taken by ambulance to St. Luke’s hospital, just outside of Utica, ten miles away. I did not learn that this had happened until a day later.

There is no evidence that this incident had anything to do with the the naming of the Irish post-punk-goth shoegaze band My Bloody Valentine whose album loveless is among the greatest in all of rock.

A brief primer on certain 1974 realities, with particular regard to life on the Hamilton/Kirkland College campus in upstate Clinton, NY

In those days people corresponded by letter, a lot, with people who didn’t live nearby. Much more than they did by telephone, when ‘long distance’ calling was quite expensive.

On the campus of Hamilton & Kirkland Colleges there were no telephones in individual rooms; there were, however, two varieties of shared phones in dormitory hallways, usually sharing a small alcove:

1 pay phone for calling off-campus — our connection to the world outside;

1 ‘centrex,’ free, phone for on-campus calls — that is, calls within our isolated hilltop Shangri-La.

Typically 20 or more students would share any two of these phones. For example, I talked with my parents a few times each month. If my father wanted to talk with me he would call the pay phone nearest my dorm room. He relied on the goodwill of anybody who happened to hear the phone ringing to answer it and then come knock on my door. When I called home I called ‘collect’ from a pay phone. To do this I dialed “O” for operator — the only call I could make that didn’t require me to deposit a dime. I told the (human) operator (virtually always a woman) my home phone number, and she placed the call. If anybody answered the phone at my house the operator would ask them if they were willing to have the cost of the call billed to their account. If they agreed the call went through — and my parents paid for it.

In addition to first class mail there was ‘special delivery,’ whereby (per wikipedia), “the letter would be dispatched immediately and directly from the receiving post office to the recipient rather than being put in mail for distribution on the regular delivery route.” A ‘special delivery’ letter was a rare & noteworthy thing. You’re sitting there in your living room, reading the newspaper. The doorbell rings. Who could it be? You open the door and there is a postman, in postman’s garb with a postman’s cap. “Special Delivery!” he says, and hands you a letter.

Due to an embargo of oil exports to the USA, gasoline was rationed across the USA. Rationing was usually done using a simple algorithm based on license plate numbers: If the last number on your plate was even, you could buy gas on the even-numbered days of the month; otherwise on odd days. There were long lines at gas stations.

There were about 1,800 students at Hamilton & Kirkland Colleges. The joint campus covered a few hundred acres. You could walk from one edge to the other in ten minutes. In those pre-cell phone days we basically sync’d up with each other through Brownian motion. Of course you could use the Centrex phones to call from dorm to dorm, but everybody was always moving from here to there. You were equally likely to run into whoever you were looking for by just walking around campus.

Some students had cars. Most didn’t. I didn’t. Why would I need a car? Where would I go?

Very slowly then all at once

Anne and I had known each other well enough to say hello for well more than a year before we actually became friends. She and her friend Jane had been two of only 5 students in a linguistics class that I took in junior year, but even so, once we connected neither of us recalled our ever having had a conversation. Our paths had crossed in other contexts too, but we had barely ever said more than ‘hello’ to each other. We’re the kind of people who, when we have nothing to say, say nothing.

But then, right around Thanksgiving, 1973, I encountered Anne when I was on my way to watch a movie in the Chemistry Hall and on a whim I asked her if she felt like going with me. She said OK. The movie got cancelled so we took a short walk, with her beloved cat Nemo tagging along. There was only one tiny place on our walk where there were cars but one came out of nowhere and ran over Nemo and killed him. Anne carried his bloody body until she was able to locate somebody from campus security to help her bury him. That was our ‘meet cute’.

Within ten days I was insanely in love with Anne, absolutely thunderstruck. Evidently she felt something too.

A conversation at the Rok

At the bottom of College Hill Road in the village of Clinton, NY, a half-mile away from the Hamilton campus is a bar called the Rok. Long ago it was the Shamrock. In the 1970’s the legal drinking age was 18 and the Rok was our place. The college operated a free shuttle between the village and the campus. It was like Disneyworld.

One night in the fall of 1973, when I was a Hamilton College senior, I was at the Rok with my friend Jeff. Now, I had accrued some credits by taking classes at Cornell one summer, so after January I would have completed my graduation requirements and would no longer be an enrolled student. I was anxious to finish college, get off “The Hill” and on to whatever came next, out in the so-called Real World.

I was talking to Jeff about applying to Peace Corps. My major was anthropology — the study of culture. My senior thesis was on the work of Claude Lévi-Strauss, the French structural anthropologist who found deep universal meaning in myths and traditions. I had a fascination with how people in traditional societies organized social relations, how they viewed the world. Ever since I was 10 years old I had daydreamed about going to live in a small village somewhere remote from 20th century America just to see what it was like.

That night at the Rok I told Jeff that I had always thought I would join the Peace Corps but now I was getting cold feet. I was concerned that 2 years was such a long time. Jeff said "two years?" and then snapped his fingers. "It's like that."

Later that night, back in my dorm room, half drunk, mindful of Jeff's remark, I filled out the application. I remember clearly that it said "If you have any agricultural experience, even if you think it's not significant, please include it" and I yet still almost didn't include mention of my own agricultural experience because I thought that growing up on a farm with 2 cows & 8 sheep & 60 chickens and an orchard and a 250 square foot vegetable garden wasn't really anything worth mentioning. But because Peace Corps explicitly asked for it I included it. Which is why I ended up in Fanaye doing famine relief and rural/agricultural development instead of being a teacher in a Senegalese high school in a town or a city like nine out of ten of the other PCVs.

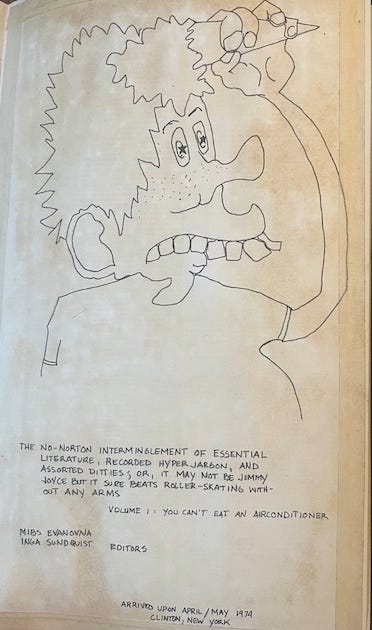

To read it well: that is, to understand

Over the last 50 years fewer than five people have seen the inside of the book that I retrieved from that post office in Dakar six weeks after my arrival in Africa — The No-Norton Interminglement that I share with you here.

It is a 168 page journal into which Anne copied stories by Dorothy Parker, James Thurber, Joel Chandler Harris, The Brothers Grimm and several others, including the complete poem The Hunting of the Snark by Lewis Carroll; entries from my diary, which I had left with her; pages from an S&H Green Stamps catalog and the catalog of Hamilton College; mawkish poems written to her by a former boyfriend; original drawings & hand-drawn copies of others and all manner of sublime things meticulously transcribed and extensively annotated — with only 4 tiny crossed-out errors in the whole book. Creating it had to have consumed virtually Anne’s every waking minute from when I last saw her on April 10, 1974 until she put it in the mail.

Living in a closet

At Hamilton/Kirkland the month of January was devoted to singular topics, called Winter Studies. For my Winter Study in January, 1974 I wrote and produced a one-act play. Anne was off-campus for that month. She was doing an independent study at the Monterey Language School, in California, where her friend Jane was now a graduate student studying Russian. Save for one brilliant post card that Anne sent me, we didn’t communicate for that entire month. I had to fear, of course, that our affair, which had lasted about one month, was already over. Nemo’s death still haunted Anne. I thought she might drop out of college altogether.

Because I had planned to have finished college on January 31 I had made no living arrangements for after that date. But now because of the whole Anne thing I wanted to stay on campus. In fact my room & board contract with Hamilton had ended at the end of Winter Study sometime around January 27th. After that I was living in a windowless storeroom — a closet, basically — in one of the dormitories occupied by one of Hamilton’s fraternities. I got a job in Hamilton’s registrar’s office, processing add/drop slips.

Then Anne came back. Hamilton found out about my illegal living arrangement & put an end to it. At some point I moved into Anne’s dorm room. I don’t remember if that was before or after she was found in a bloody puddle in a gym-building hallway.

Men, they build towers to their passing years to their fame everlasting Here he comes chopping and reaping hear him laugh at their cheating Time waits for no one, no favors has he Time waits for no one, and he won't wait for me

Shifted reading frames

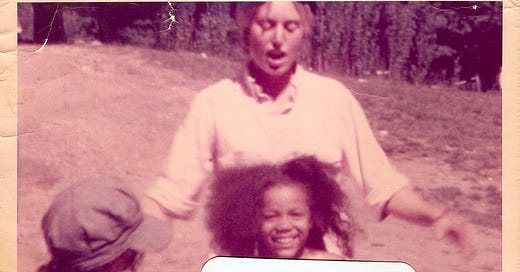

Here is a photo of my wife Betty, taken just before she and I met as graduate students at Purdue University in 1978. I was working on a degree in agricultural economics — studying smallholder farming systems in the Senegal River valley. She was working on a PhD in molecular genetics. In particular she was studying overlapping gene products and shifted reading frames in single-stranded DNA bacteriophage. We got married in 1980. Her name seems to come up regularly in this ongoing autobiographical meditation.

Breathless

Anne had been in St. Luke’s Hospital near Utica for nine days. I remember very little about that period. I spent my days working in the registrar’s office, separating and filing the three sheets of the triplicate add/drop form: one sheet went into the folder of the class being dropped; one for the class being added, one into the folder that kept that student’s academic record. I visited Anne in the hospital a few times but I don’t remember much about doing that other than that on one visit I donated a pint of my O+ blood, and that once Jane, who had come all the way back from California to visit her gravely ill friend, gave me a ride from the college campus in Clinton to the hospital in Utica.

On the cold clear day of February 23, 1974, I was walking somewhere near Dunham Dormitory when a person — I’ll never remember who — came sprinting up to me, breathless.

“John! John!” They said, gasping. “Everyone on the whole campus is looking for you! A doctor called from Utica. You have to get to the hospital absolutely as soon as you can.”

To be continued. . .

Addendum: the story continues in Jerrycans full of gasoline in the back seat (2)

Another vote for writing as quickly as the “Dickens”

Thank you. I read that thing a dozen times before posting it and as soon as I posted it I found three typos. Sigh.