My greatest problem, part two

Yes, that is some kind of bust

Précis

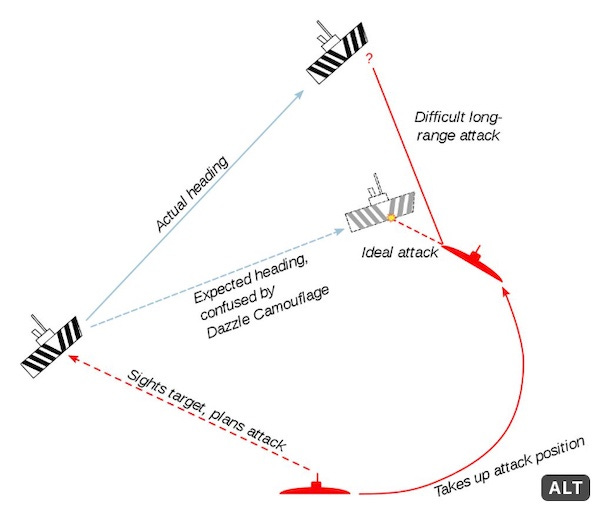

This post is a continuation of my immediately prior post, My greatest problem, part one, in which I discussed, among other things: an aborted attempt at writing a screenplay based on Sunset Boulevard about the Trump White House; Homeric epithets and fate, “dazzle camouflage” painted on pre-radar ships; brainworms and dementia.

This post, like the one before it, is about my greatest problem. In part one I did not say what that ‘greatest problem’ was, but let me stop being coy:

It is Causation that is my greatest problem

Actually that’s only half of it, but we can start there.

Aeschylus to Aristotle to Feynman to Bell

So let’s talk now about the meaning of “causation.” (You may be wondering, as I was, what the difference is between “causation” and “causality.” Long story short although in certain specific (legal) contexts these words have different meanings, for our purposes they are the same. Causation, causality — as old Mr. Ristucci, proprietor of Ristucci’s Bakery in Singac, New Jersey, explained to me one Saturday evening in 1969 when I asked what the difference was between French bread and Italian bread (as the lettering on his delivery trucks advertised both), “It’s-a no diff. Only da bag.”)

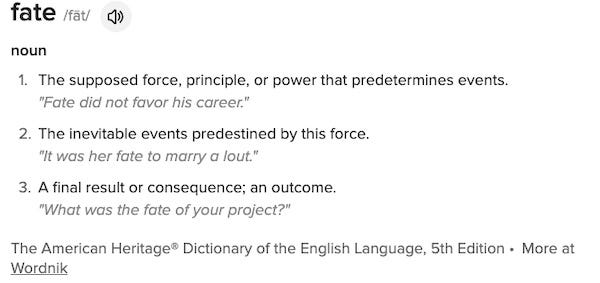

The ancient Greeks believed deeply in fate, meaning that one thing leads inexorably to another and there ain’t nothing nobody can do about it.

The theme of fate pervades ancient Greek dramaturgy. Consider, for example, the opening scene of Agamemnon, the first play of Aeschylus’s Oresteia:

Wikipedia: The Oresteia (Ancient Greek: Ὀρέστεια) is a trilogy of Greek tragedies written by Aeschylus in the 5th century BCE, concerning the murder of Agamemnon by Clytemnestra, the murder of Clytemnestra by Orestes, the trial of Orestes, the end of the curse on the House of Atreus and the pacification of the Furies (also called Erinyes or Eumenides).

The Oresteia trilogy consists of three plays: Agamemnon, The Libation Bearers, and The Eumenides. It shows how the Greek gods interacted with the characters and influenced their decisions pertaining to events and disputes.

In the very first scene of Agamemnon, a watchman sees a beacon fire in the distance and knows that King Agamemnon has returned to Greece after ten years away at Troy. How does the watchman know this? Because very many miles away away another watchman had lit a fire as soon as he had seen Agamemnon’s ship on the horizon, and, upon seeing that first fire a second watchman had ignited the bonfire that he had prepared in anticipation of that first one, which (new) bonfire was seen in turn by the next watchman in the chain, and so on, cha-la-lal1. And thus, by a series of fires, news from of the king’s return is inexorably communicated to his waiting wife — fire, fire, fire, boom, boom, boom, one thing leads to another: Causation.

Then a couple hundred years later along comes Aristotle with his slightly more sophisticated take on causality/causation (as was discussed in part one). In the Aristotelian sense, a “cause” is an explanation, an answer to the question “why?”

Then a couple thousand years after Aristotle along comes the physicist Richard Feynman with his take on the question of “why.”

This video is seven and a half minutes long but you really owe it to yourself to watch it. If not now then some other time, preferably soon.

Feynman received a Nobel prize in physics for his work on quantum mechanics. He was an extremely smart man. Some say he was the second smartest man ever, as smart as Norma Desmond, almost as smart as Donald Trump. In fact the very excellent biography of Feynman by James Gleick is called Genius, that’s how smart Richard Feynman was.

As discussed in my brilliant if a bit discursive essay Entanglement, quantum mechanics asserts that quantum entanglement is a feature of reality — and experiments based on the theories of the physicist John Stewart Bell prove that that’s true — and that fact — the fact that quantum entanglement is a feature of reality — calls into question the very notion of causation — indeed, of reality itself — for reasons that, borrowing the words of Feyman at the end of the above video, I cannot explain in terms you’re more familiar with because I do not understand it in terms you’re more familiar with.

Where is Daniel Dennett?

Daniel Dennett, the noted philosopher2 is, alas, deceased. So I do not ask where he is in that sense. Rather, I’m alluding to an essay he wrote called “Where am I?” in which he raised several intriguing questions about brains, minds, selves, and so forth. Here is a summary of that essay by Lance Mann:

In his paper, “Where Am I?” Daniel Dennett presents a philosophical theory of personal identity. He illustrates a thought experiment in which his brain disconnected from his body and placed in a vat in Houston, Texas while his body is sent on a mission to recover a warhead beneath the surface of the earth in Tulsa, Oklahoma. His brain is still connected to his body and able to control his tasks through radio links. Dennett then proposes the question of, “where am I?” If his brain is in a whole different location than his body, then where is his personal identity? For the following thought experiment, he names his brain, “Yorick,” his body “Hamlet,” and he, his identity, is Dennett. He presents three possible answers to the question, “where am I?”

Dennett’s story has several intriguing turns and raises issues too deep to be more than mention here. Other writers3, especially writers of science fiction, have raised similar questions before Dennett, but his essay brings into sharper focus several of the philosophical issues raised by those kinds of stories. You can find several analysis of “Where Am I” online. Lance Mann’s essay is a good a place as any to start.

The Problem of Tuvix, to which I have alluded a few times in this essay but not yet addressed, raises related philosophical issues.

Poetry

In part one of this essay I told you that one day last week4 I woke up at 4 AM with my head so full of ideas about Elon Musk’s ‘Neuralink’ brain implant and Bob Kennedy’s dead brainworm that I got out of bed to write them down, but that, once I had sat at the desk under the skylight in my attic office my attention had shifted from those thoughts of Musk, Kennedy, brains and so forth, to thoughts of a line in a poem that I first read in 1972, when I was a student at Hamilton College.

I will tell you what that line is, but first, since it is from a poem by a poet whose work I have already mentioned on Sundman figures it out! at least three times, I would like to assure you that I like the poetry of lots of poets, not just the one whose line I will type here shortly.

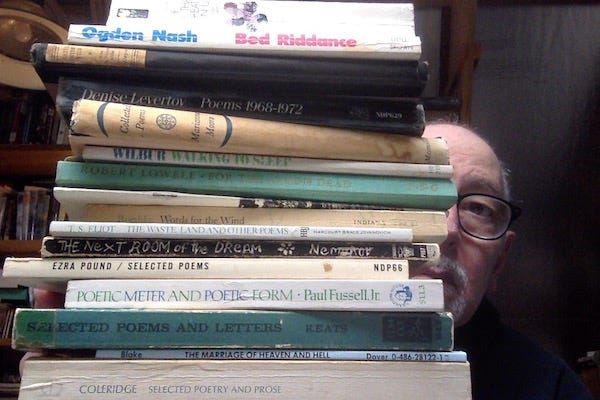

As evidence, here are is a photo of books of poetry I own and read. The type is hard to read on some of these covers so let me list some of the poets: Robert Burns, Richard Wilbur, Ezra Pound, John Keats, Mariane Moore, Howard Nemerov, Theodor Roethke, Robert Lowell, Edna St. Vincent Millay, T.S. Eliot, William Blake, Samuel Coleridge, W.B. Yeats, Denise Levertov, Emily Dickinson.

The line that displaced my Musk/Kennedy thoughts is from the poem “Taking a Walk with You” (a poem which scholars of Sundman figures it out! will recall was first mentioned in the essay Sundman’s Awful Mistake, part two, under the heading “Misunderstanding as a subcategory of mistake”. That line is

It is Causation that is my greatest problem And after that the really attentive study of millions of details.

So now we see that the really attentive study of millions of details is the other half of my greatest problem, or, if not exactly part of my greatest problem, close enough. So we need to talk about that too.

If, by some calamity, you have misplaced your copy of The Collected Poems of Kenneth Koch, here is a link to Poetryfoundation.org where you can read Taking a Walk With You.

Dazzle schematically

As discussed in part one, my Blue Sky friend c0nc0rdance recently posted a fascinating thread about ‘dazzle camouflage,’ which, before radar made it obsolete, was painted on merchant ships to confuse targeters on hostile warships. Here is an image from that thread.

There is a connection I wish to make between Sunset Boulevard and dazzle camouflage, and fate and that fortune cookie fortune to which I earlier alluded to, but we are not quite there yet.

Tuvix and “telepathy”

I have prepared this summary by editing the Wikipedia entry for “Tuvix”:

"Tuvix" is the 40th episode of the science fiction television program Star Trek: Voyager. The episode originally aired on May 6, 1996, and tells the story of Tuvok and Neelix being merged into a unique third character named Tuvix:

On stardate 49655.2, Lieutenants Tuvok and Neelix are sent to collect botanical samples from a class-M planet. When beamed back aboard Voyager, the two men and the Orchidaceae they collected are merged at the molecular level to become a single lifeform which names himself Tuvix. The crew discovers that when demolecularized, the genetic material of the alien orchids acted as a symbiogenetic catalyst and is the culprit for the combination of the two crewmembers. Unfortunately, the process cannot be reversed, and Tuvix is accepted as a member of the crew with the rank of lieutenant, functioning as chief tactical officer in Tuvok's stead.

Kes reacts poorly to Tuvix, as his existence deprives her of both Tuvok and Neelix, her mentor and boyfriend respectively. Her displeasure lessens over the course of the episode, but never completely goes away. Captain Janeway accepts Tuvix in his role as an excellent chief tactical officer and "an able advisor, who skillfully uses humor to make his points". Tuvix himself, having the combined memories and personalities of his constituents, melds the previously intractable qualities of both and improves upon them: "Chief of security or head chef, take your pick!"

Two weeks after the accident, the Doctor develops way to use the transporter to disentangle the two men. However, Tuvix denounces the procedure; he argues that he has rights and to restore the two lost crewmen would require his execution. After discussing the situation with Commander Chakotay, Kes, and Tuvix himself, Janeway ultimately decides to proceed with the separation, acting in absentia to protect the rights of the two constituent men.

After the Doctor refuses to take Tuvix's life in compliance with the medical precept of doing no harm, Janeway performs the procedure herself and succeeds in restoring both Tuvok and Neelix.

In part one I included a stylized representation of Elon Musk’s Nuralink device embedded in a human brain. Now imagine two such brains connect by some kind of bilateral protocol. Are we in Tuvix territory yet? How does or doesn’t Dennett’s philosophy of the location of the self apply to this question?

Extra credit question!

To what extent were issues like these anticipated in Sundman’s Mind over Matter trilogy — especially in Cheap Complex Devices and the ‘Todd-in-a-coma’ subplot of Acts of the Apostles?

Causation Boulevard

Before the events of January 6 made clear to my friend Bijan and me that there was no point in continuing with our attempted screenplay (Sunset Boulevard/Pennsylvania Avenue), I purchased and studied a copy of Sunset Boulevard.

I also took an online course — I think it was from Wondrium? — about screenwriting. It was pretty great. I think I might take it again if I can figure out where it was. That’s where I learned about fate in the classical era Greek plays, including the explanation of how the message passed from one bonfire to the next in the opening scene presages what’s going to happen in the play.

Some kind of bust

Well, will you look at that. I ran out of space again! And once again I’ve left lots of loose ends, and I haven’t even talked about the really attentive study of millions of details. I guess I’ll need one more essay to wrap up this ‘greatest problem’ essay. I hope you don’t think that that makes this whole thing some kind of bust! Indeed I very much hope that you’ll join me Real Soon Now for My greatest problem: part 3, the stunning conclusion.

You should watch this 11 second video. It’s very important.

Cheerio!

[Edit June 24/2024: This essay conclude with My greatest problem — the dramatic conclusion.]

Or, more correctly spelled, ćalalal, the word for ‘chain’ in the Pulaar language as spoken in Futa Toro, northern Senegal. At sunset in the village of Fanaye Dieri in 1975 you hear the children laughing and singing as they play the ćalalal game — a chain of children. Where are those children now?

With whom I once dined in the company of Douglas Hofstadter and a few other brilliant people (including Geoff Arnold, founding a subscriber of SFIO), as mentioned in part one and discussed at length in my essay A scared firefighter up in the bucket.

Including me. See Cheap Complex Devices.

It actually might have been as long as ten days ago.

Coincidentally, I only relatively recently watched that video where Feynman goes to task with the foundational notion of the question asked of him. It's entertaining and insightful. It reminds me in a way of Mindy and her nested "Why?" questions (https://youtu.be/TR-qdjtyYyc).

The Star Trek episode you mention is one that stayed with me since I first watched it as a young lad. It was prime sci-fi. Interestingly, through my work in studying the brain as an adult, I was exposed to the notion of there possibly already being two personalities (after a fashion) inside our skull. I worked briefly with a child who was born without her corpus callosum and went down a rabbit hole of reading. As it turns out, in extreme cases of epilepsy, adults (at least used to) sometimes undergo surgery which severed the corpus callosum. I often think about it as going from broadband to dial-up in terms of hemispheric communication (the cerebellum picking up the slack). The weird outcome of this was what appeared to be independent and often competing consciousness coexisting inside the same head. One dominant (can freely communicate via speech etc.) and the other present but only able to act out via, say, undoing the shirt that was just buttoned, or drawing something that the dominant consciousness couldn't visually perceive when presented to the eye that corresponded to the non-dominant hemisphere; the whole contralateral set-up making for confusing and darkly humorous outcomes. It brings into question the very notion of the self.

Anyway, as always, your writing is stimulating and a joy.

You had me at Feynman. HUGE Feynman fan! Huge! His two memoirs are MUST HAVES and the Gleick book is wonderful too. And then you go and throw Daniel Dennett into things, and well, you had me at hello!