New here?

Welcome to Sundman figures it out! Here, themes emerge, fade, reappear and interleave; incidents ramify and their import sometimes changes upon being revisited. Wherefore you may find that reading earlier posts will enhance your experience of reading this and subsequent essays.

Recapitulation & prospectus

This is the second post in a 3-post series.

Part one started on as a riff on a recent substack essay by Lucian Truscott about a small adventure he had in lower Manhattan in 1969 when his search for a particular valve to fix a leak in some ancient plumbing turned in to a kind of Joseph Campbell Hero’s Quest on a miniature scale.

Truscott’s post set off a cascade of involuntary memories:

of my own meanderings in Truscott’s lower-Manhattan in 1969;

of hardware-related quests with heroic overtones;

of some encounters I’ve had with ancient plumbing;

of mistakes I’ve made.

Tuscott’s poetic reflections on the slabs of Pennsylvanian blue slate that was once used to construct sidewalks in the five boroughs of New York — and which are still visible here and there — for instance in sidewalks of the neighborhood of Park Slope, Brooklyn, in which I am sitting as I type these words — reminded me of how I was once involved in repurposing some blue-slate sidewalk slabs. I was 13 years old, a man-child on a construction crew, just starting to learn how to put my back into it. Yes, we dug up those slate slabs from the sidewalks of the Beattie mansions , my brother and my father and Uncle Harry and I, and we placed them in an elegant winding path from Grandview Avenue to the front door at number 93. (But don’t bother to look for that path now: the front yard at 93 was long ago replaced with a hideous driveway, so it goes.)

And so Truscott’s musings about slate-slab sidewalks in New York got me thinking about a 19th century carpet mill in New Jersey that faded out of relevance in the 20th century— the products of its massive looms no longer wanted, its stories disintegrating in aging brains, its essence becoming oblivion.

I included a few teasers in part one — about a plumbing incident a stately house my wife and I owned long ago; about a hardware quest undertaken by my father on his father’s instruction in 1965; about salvaging parts from a Queen Anne mansion marked for demolition in 1967; about an observation made by Frank Kermode in his treatise on literary theory, The Sense of an Ending.

Most notably, I included a teaser about my recollection of one particular plumbing adventure in that grand house of faded glory in Gardner, Massachusetts, that my wife and I once owned — Gardner, “Chair City,” a city with its own shuttered mills and forgotten stories — which reminded me of Robert Quackenbush’s wonderful book Henry’s Awful Mistake, about a duck and an ant and a shattered water pipe.

Henry’s Awful Mistake, in turn, got me thinking about other awful mistakes of my own.

And so here we are in Sundman’s Awful Mistake, part two. In this installment I’ll resolve some of those teasers from part one and introduce a few new teasers to be resolved in part three.

But mainly today I want to look a bit more seriously at the whole notion of ‘mistake’.

Mistake. You keep saying that word.

But wait, what about that hardware in Bloomfield?

As recounted, my grandfather, Pop, sent my father, Dad, to an address in Bloomfield to purchase hardware for the house they were building. “Tell him your name and say you want a good price.”

So a few days later my father drove down to Bloomfield. He came back a few hours later with a small truckload of hardware and plumbing supplies. When I asked the owner how much I owed him, my father told me, “he said, ‘Nothing. It’s free. Say hello to your father for me.’ There must be three thousand dollars worth of stuff in there,” my father said.

It so happened, I learned, that in the late 1920’s Pop, a refugee who’d been in the country only about ten years, had opened his own garage. One day a man came in with a car that needed a lot of work. Times were tough, it was hard to find work. “I don’t have any money,” the man said. “But I really need the car. Can you fix it for me on credit?” Pop said OK. Pay me when you can.

Times got worse. They called it the Great Depression. The man whose car Pop fixed couldn’t find a job. Pop lost the garage and started drinking too much. My father was sent to live with some of Nana’s relatives in Connecticut for a summer.

Eventually things started getting better. Pop stopped drinking. The man with the broken-down car opened a hardware and plumbing supply store in Bloomfield.

Reconsidering Henry Duck

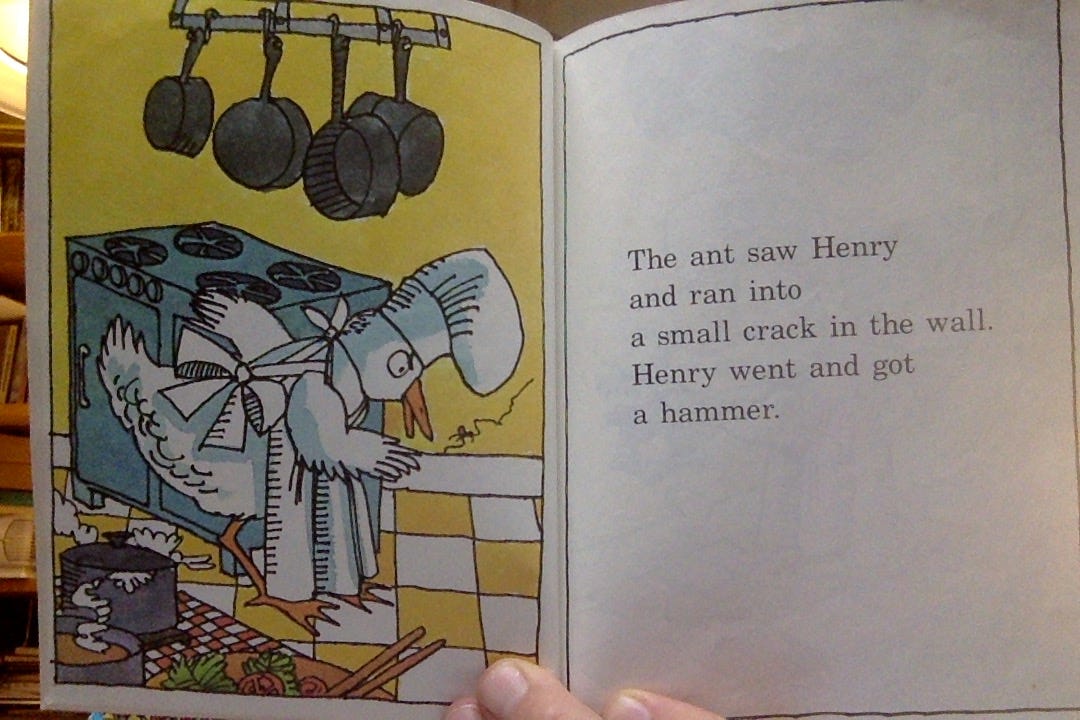

In part one I was perhaps a bit glib about Henry. We’re tempted to take his story as a funny one, to read it for laughs. But I bet it wasn’t too funny for Henry! I think we should give him a little more consideration. Let’s take a closer look at the inciting incident. Here are few key scenes:

It looks like a lovely kitchen, quaint and unpretentious. Henry certainly doesn’t look like a violent fellow.

We’ll skip over the parts where Henry decides against using insecticide, moves the stove away from the wall (after turning off the flame) and makes his first attempt at ant-smashing with a frying pan.

In part one, we saw that Henry’s intemperate drive to kill the ant with the hammer led to his smashing a pipe and creating a massively gushing leak. We didn’t see the conclusion, so I’ll tell it here: Henry’s various attempts to stanch the torrent all prove unsuccessful. By the time Clara arrives the house has been destroyed and the debris from it, as well as all of Henry’s worldly goods, are being carried away by the waters.

Misunderstanding as a subcategory of mistake

Reach up on that bookshelf behind you and take down your copy of The Collected Poems of Kenneth Koch. Turn to page 143 and read the opening lines of “Taking a Walk with You.”

Taking a Walk With You

My misunderstandings: for years I thought "muso bello" meant "Bell

Muse," I thought it was kind of

Extra reward on the slotmachine of my shyness in the snow when

February was only a bouncing ball before the Hospital of the Two Sisters

of the Last

Hamburger Before I Go To Sleep. I thought Axel's Castle was a garage;

And I had beautiful dreams about it, too — sensual, mysterious

mechanisms; horns honking, wheels turning. . .You can be forgiven for not knowing that Axel’s Castle: A Study in the Imaginative Literature of 1870–1930 is (according to Wikipedia) “a 1931 book of literary criticism by Edmund Wilson on the symbolist movement in literature.” I didn’t know that either, until I looked it up five minutes ago.

About Edmund Wilson, well, what is there to say? His history of socialism and prehistory of communism, To the Finland Station is OK if Reds with Warren Beaty and Diane Keaton wasn’t long and boring enough for you. I know Wilson couldn’t manage to get along with Vladimir Nabokov, but then, who could get along with Nabokov, really? More to the point, Wilso was a beast to his sexy wife Mary McCarthy, and, well, Mary McCarthy was a hot ticket who finally had just about enough of Edmund fancy-pants Wilson, as she made clear in her legendary New Yorker magazine story “The Weeds”, just say’n.

I actually don’t know anything about Wilson’s literary criticism, and besides, we’re already getting more than enough literary criticism here in Sundman figures it out! from Frank Kermode, don’t you think? So I hereby promise you that Axel’s Castle will never again be mentioned in Sundman figures it out!, ever. And I’m not even going to mention Kermodes’s The Sense of an Ending again until part three. If you really want to know what I think, it was a mistake to even bring up the subject of Edmund Wilson in the first place.

I was planning to intersperse more snippets from Kenneth Koch’s long and wonderful poem “Taking a Walk with You” in this essay, but I did not bring the book of Koch’s poems with me on my current trip to Brooklyn, and I can’t find that poem online. So I guess that’s it for now, Taking-a-walk-with-you-wise.

About that leather washer

In part one I included a teaser about a leather washer I needed to find in Gardner, MA, in 1986 to fix a leak in a Victorian faucet. Well it turns out that finding the leather washer I needed was no problem; an old-timer recognized my worn-out washer right away and found a new one in a back room. It cost me about seventy-five cents. So that teaser is now resolved.

I don’t have anything else to say about the Beattie mill or mansions, or about other things we salvaged from them, besides the slate slabs, for the new house at 93 Grandview. I think there were a few other teasers left hanging from part one but I’m not going to worry about them now. Maybe some other time.

A mistake at third base

I wasn’t a really obese kid in grade school, but I was what they used to call ‘husky’ or ‘chubby’. I wasn’t terrible at sports, but I wasn’t great at them either — I was somewhere in the bottom third of kids my age.

I started playing in a softball league when I was about eight and baseball when I was about ten. If there were 15 kids on the team, I was about the 12th best player. I got a hit once in a while, or managed to work a walk, but striking out was a much more common occurrence.

One day when I was about 11 years old I was in a Little League game at Gould Avenue School. I came to the plate in a late inning; our team was down by a run and there were two kids on base. It was the exact kind of situation where I and everybody else would expect me to strike out.

I stood in the batter’s box, the pitcher pitched, I swung hard and I saw the ball go sailing high over the right fielder’s head. If there had been an outfield fence the ball would have carried over it for a home run. But there was no outfield fence at the Gould Avenue School field.

Every body began yelling “Run! Run!” and so I took off for first. When I got there the first base coach was yelling “Run! Run! and I took off for second, and then for third. Where I stopped. The third base coach said “Run home! Run home!” But I hesitated. I looked to the outfield. The right fielder was picking up the ball. “Run! Run!” everybody was yelling. But I just stood on third. Until, at last, the coach said, “Too late now. Stay here.”

I had just suffered a case of early-onset impostor syndrome. At some level I didn’t think of myself as the kind of kid who was allowed to hit home run. So I settled for a triple.

Hitting a triple was nice, of course; driving in the winning runs was nice. Having everybody cheer for me was nice. But I finished my Little League career a few years later having never hit a home run.

Between the ages of 16 and 18 I grew from 5’8 to 6’3. I became an OK basketball player and an OK surfer. In college I became an almost-OK hockey player. I wasn’t a chubby kid any more. And besides, I always tested in the 95th percentile on things like SAT tests, so that was always a kind of consolation.

Over the past sixty years I’ve thought about my mistake, the hesitation that cost me a home run, more times than you can imagine. And that kid standing on third believing that he’s not worthy of hitting a home run is still a part of who I am today, sixty years later.

Of course I’ve made much worse mistakes than not running from third to home in my life. Incalculably worse mistakes. Haven’t you? But those are the kind of things I only share with Jesus and my wife Betty, and Jesus is imaginary.

But what was Henry’s mistake, actually?

If you asked a casual reader what Henry’s awful mistake was, they would probably say, “hitting the pipe with the hammer.” I don’t find that very satisfactory. Because why did he hit the pipe with the hammer?

Was it because he was overly concerned with what Clara might think of him? Was it because he didn’t trust Clara to not freak out over an ant? Was his mistake not taking into account that maybe the ant had friends and family who loved them? That maybe the ant had a right to live? That maybe he should just leave it the fuck alone?

Was his mistake his decision to go for a hammer once the ant had found that crack? Was it surrendering to rage and losing all sense of proportion? What was it? What! What was Henry’s awful mistake, God damn it? You tell me!

It certainly seems that we have a lot to talk about in part three! Including the story of that busted pipe in Gardner, and the wonderful easter egg I discovered because of it.

A friend wrote me privately and gave me permission to post this here:

"A few years ago I was getting a haircut in Rochester. I told the hairdresser I wanted to get it cut before leaving the country. She asked where I was going. I said - perhaps not very clearly - "Moscow." Which led her to ask, "Do you speak Spanish?"

When I tell this anecdote to German or Russian friends, they put it down to legendary American ignorance. That's also what I took it to be for a while. Somehow, though, that didn't feel like a sufficient explanation.

I thought back to the continuation of the conversation in the barber shop. It turned out that the hairdresser's boyfriend was from Mexico. In retrospect, I think that's a key fact.

It had likely never happened to her before that that a customer had said he was going to Moscow, but people she knew went to Mexico - as she was perhaps also thinking of doing.

We all have horizons of expectation – and if we experience something that does not fit into the horizon, we tend to interpret it so that it does fit. When I mumbled "Moscow," that was literally unbelievable to her ears, so she figured I must have said "Mexico." She took what was nonsense from her POV and turned it into sense.

Probably relatively few errors are caused by simple ignorance. More are caused by the incorrect interpretation of possible meanings."