New here? Howdy!

Welcome, new subscriber, to Sundman figures it out!, an episodic autobiographical meditation. Here, themes emerge, fade, reappear and interleave; incidents ramify and their import sometimes changes upon being revisited. Wherefore you may find that reading some of the earlier posts, according to your fancy, will enhance your experience of reading this and subsequent essays.

Précis

Over three posts a reminiscence of Olde (~1969) New York by a fellow substacker occasions discussions of the repair of ancient plumbing and the recycling of some appurtenances of a 19th century carpet mill in New Jersey; I consider the human propensity to discount our own errors and misunderstanding while taking note of the foibles of others; we tell the tale of a very clever plumbing-related Easter egg at a magnificent white-elephant of a house in Gardner, MA; I comment on the Paul Anka/Frank Sinatra song “My Way;” I allow as how I may have made one or two mistakes in my life, and bravely discuss one of them, from my boyhood, which resonates still today; and, despite my best efforts to de-snootify this sometimes high-falutin’ Sundman figures it out! chronicle, I feel compelled to investigate just one more brain-scrambling passage of Kermode’s The Sense of An Ending1 (or maybe two).

Also, of course, we digress, as is our wont.

Part one of three parts.

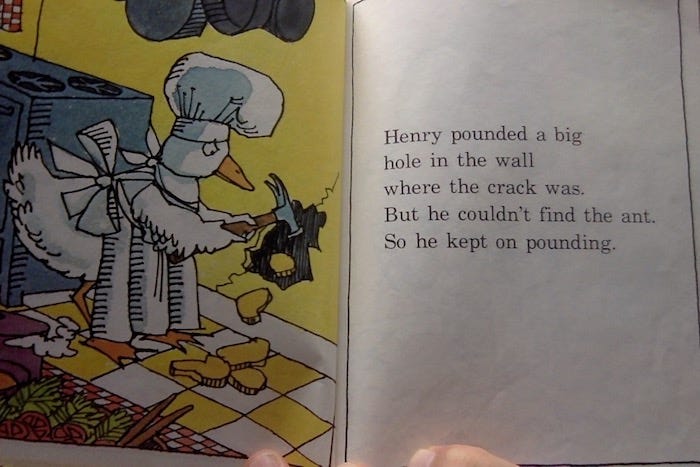

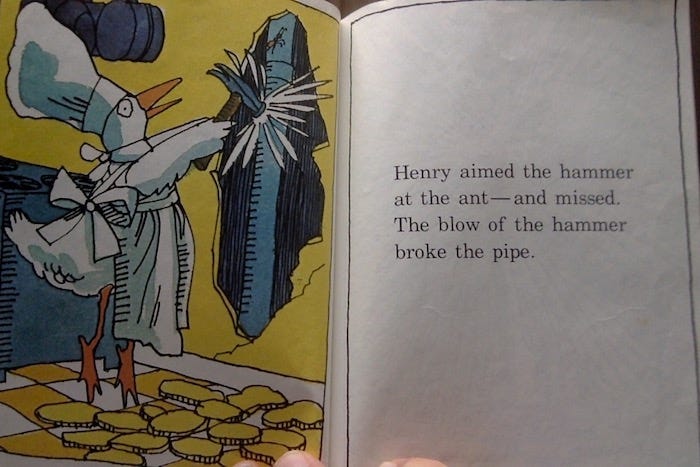

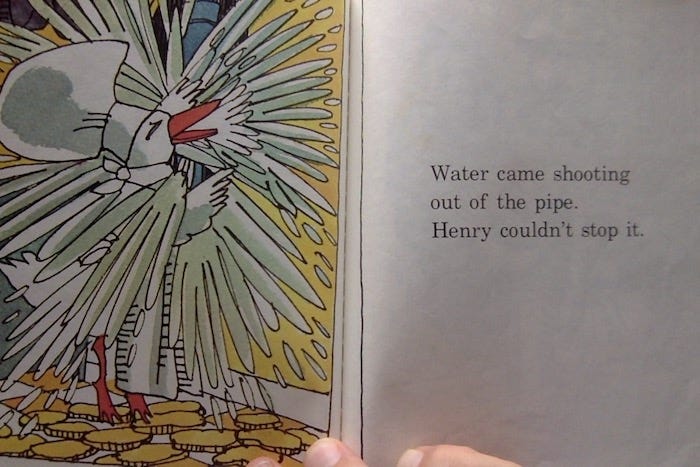

But first, Henry Duck: Isn’t it time we forgave him and moved on?

Henry made a mistake. But haven’t we all? So shouldn’t we just let it be? For as Jesus said, Let {whoever be among you who has not smashed a fragile water pipe with a hammer while trying to clobber an ant} cast the first stone.

About my own smashing of ancient and fragile water pipes, the less said the better. Honi soit qui mal y pense2, that’s what I say.

Truscott

I’m a paid subscriber to New Yorker writer Lucian Truscott’s cleverly-named substack, Lucian Truscott Newsletter, which mostly concerns our current socio-political predicament: the war in Ukraine, Trump, and fascism. To lighten things up, Truscott sometimes mixes in a cat-centric post or a vignette from his days as a West-Point-educated bohemian in New York City in the 1960’s and 70’s.

Recently he wrote about a long-ago expedition through the byways of pre-gentrified lower Manhattan to find a particular kind valve to repair a gushing leak in some antediluvian plumbing under a 19th century sink in the corner of dusty of the industrial loft he then called home:

Up the stairs [from Truscott’s quasi-legal squat] was a toy factory where they made children’s toys from steel sheets, painted and folded and held together by little tabs that fit into slots. You could hear them up there, hammering the stuff when something didn’t fit, and boxing it up, and occasionally I’d run across one of the workers carrying a cardboard box containing either the sheet steel the things were made of on his way upstairs, or the completed toys, like fire engines and dump trucks in new cardboard boxes on his way downstairs.

[. . .]

So, I turned off the water supply pipes under the sink and used a crescent wrench to take the faucet apart. When I got the hot water valve out, I could see why it was leaking so badly.

The rubber washer was completely missing. The only thing holding back the water when you turned it off was a little brass cup with the brass screw that held the missing washer in place. I took the valve and walked down the block to a hardware store that stood for years at the corner of Houston Street and LaGuardia Place and went up to the service desk and asked them if they had a replacement.

“Nope, you’re going to have to see Benny Thompson on Lafayette for that one. Number 173, almost to Grand. Can’t miss it.”

So Truscott (the 1969 model Truscott, remember), heads to Lafayette Street, making fruitless stops at hardware stores along the way in search of a suitable replacement for the busted valve from under his kitchen sink, but everyone tells him the same thing: “You’ve got to see Benny for that one.” Eventually Truscott gets to the address he’s been given for Benny’s place:

It was a huge loft, nearly a half-block long, and from an area I couldn’t see, I could hear machines whirring and grinding and the banging of some kind of stamping machine.

A guy appeared and I asked if this was Benny Thompson’s place. He said, “I’m Benny. Whatcha need?” I held out the little brass valve. He barely glanced at it before pointing to a wheeled canvas basket. “Over there. Take whatever you need.” I looked in the basket, that had to be three feet on a side and three feet deep. It was filled with the exact brass valves I was looking for, which were being manufactured right there in the big loft. I grabbed a couple of them and asked him how much. “Seventy-five cents okay with you?” he asked. “For one?” I asked, holding the valve in my hand. “Gimme a dollar and take three,” he answered.

I felt a couple of connections to this essay. Firstly, in 1969, while Truscott, a few years older than me (and a few years out of West Point and a year or two out of the Army), was exploring the starving writer’s lifestyle in lower Manhattan, I was a student at (Jesuit/ROTC) Xavier High School about a one-mile walk away from Truscott’s loft. As a West Point cadet, Truscott had marched in military uniform to classes on the lovely campus of the United States Military Academy. I, on my way to class, had ridden the subways of New York City similarly attired.

I was familiar with the old manufacturing neighborhood (on the boundary between Greenwich Village and the East Village) about which Truscott waxes nostalgic; I used to walk through it on Friday nights on my way to see Jethro Tull or Taj Mahall playing at the Filmore East.

The house at 93 Grandview

Sometime around 1965, when the town took the old farmhouse at 31 Grandview Avenue3 by eminent domain so they could build West Essex Regional High School on the land behind where our pasture used to be so that Meadow Soprano could go to classes there thirty years later, my father, ‘Dad,’ and his father, ‘Pop,’ decided to build a house a quarter mile up the road on a two-acre parcel of land — an open field which they purchased from Miss Sanderson, a dignified septuagenarian who lived alone in a stately Queen Anne at the corner of Grandview and Squire Hill Road.

The new house was to be a side-by-side duplex: one side for my parents and my six brothers and sisters and me, the other side for Nana and Pop. To get from our apartment to Nana and Pop’s, you would go via the back porch, or through the garage in the basement, or you could go all the way around the outside of the house and through Nana and Pop’s front door on the far side.

I was 11 years old when ground was broken for the new house. In those days my father worked in finance in Manhattan, 20 miles to the east. Pop still worked at the garage in Newark, twenty miles in a slightly different direction. Although my father had no background in construction, he took it upon himself to be (in his alleged ‘spare time’) the general contractor on the job.

Dad hired the architect, the carpenters, the masons and plumbers. He managed the budget and purchased the materials. Pop (in his spare time) did the wiring and made all the cabinets for the kitchens and bathrooms. My brother Mike and I were conscripted as laborers on weekends and every day of summer vacation. We dug ditches, mixed cement, swept floors, moved building materials and construction debris from here to there.

Meanwhile down the hill at the farmhouse at 31 Grandview, Mom took care of the house, the farm animals, and seven children. Nana helped.

Henry’s awful mistake started innocently enough

OK it wasn’t all that innocent. I mean, he was, after all, chasing an ant with a hammer. But like I was saying, Who among us hasn’t done something like that?

The Beattie Mill and its grand houses

In what is now Little Falls, New Jersey, in 1840, Robert Beattie, who was, like Nana, an immigrant from Ireland, founded a carpet-making company and constructed a mill near a waterfall on the Passaic River.

By 1850 or so, things were really hopping here in the U.S. of A. People arrived on these shores from all over! Mothers with their babies! They built houses to live in, and they purchased carpets to put on the floors of those houses! The Beattie Carpet Company became very successful! The mill grew and grew! Robert Beattie became very rich! Private enterprise in America!

The Beattie family retained ownership of the company. They became ever more wealthy and they built grand Queen Anne houses for themselves on main street, on the opposite side and a little ways down the road from their colossal carpet mill. From the porches of their beautiful homes they were afforded lovely views of the ceaseless falls, upon which their forbear Robert had gazed and had a vision of a mill. Leading up to those porches were grand walkways made of thick blue slate.

In the twentieth century the carpet business slowly faded. One by one the giant looms of the Beattie mill were turned off; the grand halls were shuttered. People who had worked at the mill for decades were laid off.

The stately old Beattie mansions fell into disrepair. The Beatties moved away. Nobody wanted to live in those old-fashioned houses anymore. They were slated for demolition.

Uncle Harry (who had lived in the farmhouse with us until he went into the Marines), knew someone who had the contract to dismantle the Beattie mansions. “Aha!” my father said.

A good price in Bloomfield

My name is John Sundman; my father’s name was John Sundman; Pop’s name (after it was changed from Reinhold on Ellis Island) was John Sundman.

When it came time to purchase hardware for the new house — things like hinges, handles for doors and cabinets, and maybe an under-sink valve or two — Pop gave Dad an address in Bloomfield. “You go to this place to buy hardware. You tell them John Sundman wants a good price.”

(I told another story about me and Pop and Bloomfield. You can read it here.)

A washer in Gardner

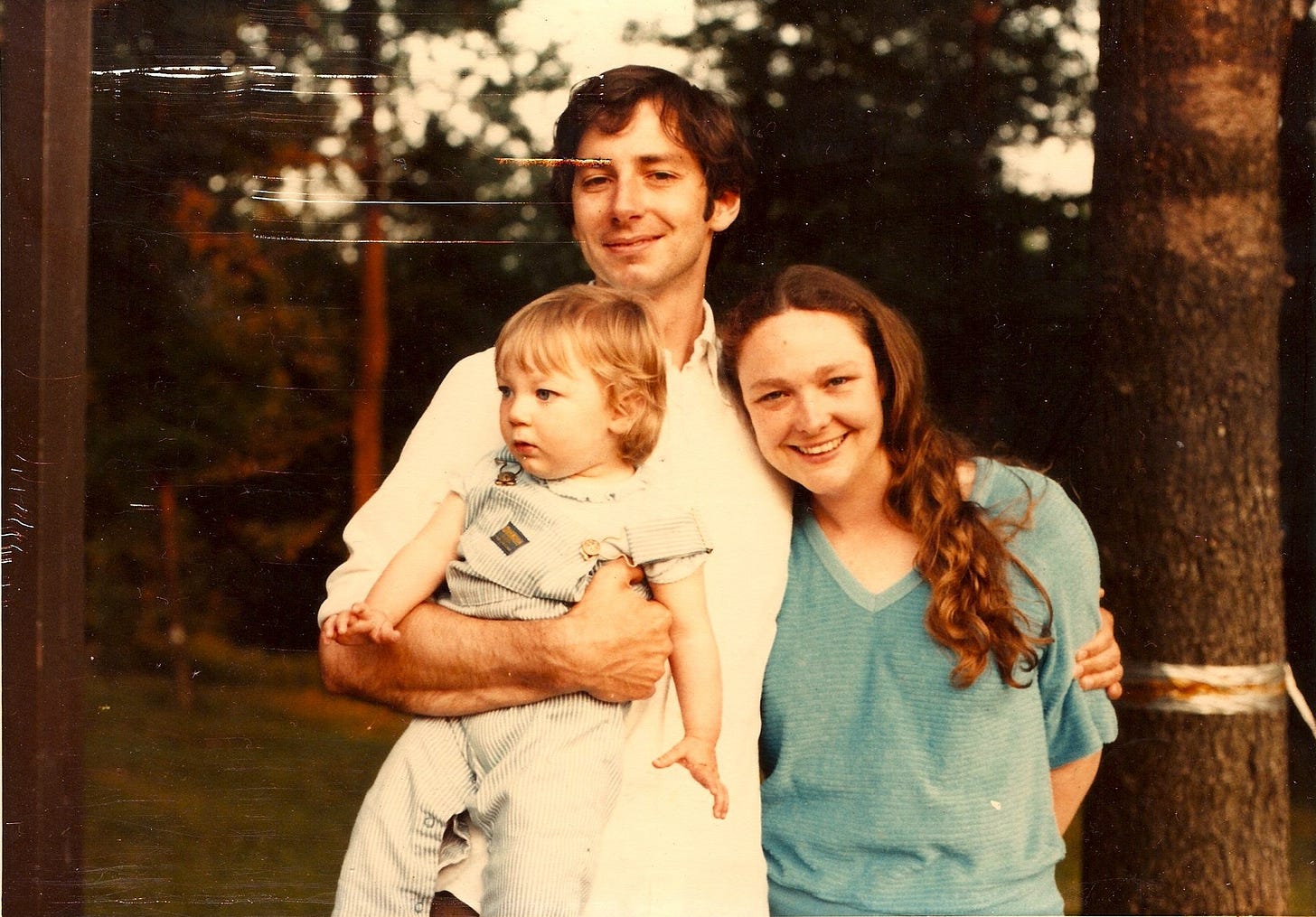

So anyway in 1980 I married that molecular geneticist with the great figure that I met at that vegetarian Thanksgiving potluck at the lesbian/feminist artists’ collective and we bought & fixed up a charming but extremely decrepit Dutch colonial house across the street from Westboro State Hospital4, and then Jainaba — named for a little girl I had known in Fanaye — joined us, but when Jainaba was three years old the noise of the motorcycles roaring down Lyman Street scared her so we decided to move to Gardner.

We bought a big old house in Gardner, as grand as a Beattie mansion. It had a slate roof and stretched-canvas ceilings and a grand formal front staircase and a narrow back staircase for use by the servants. It had a fireplace in the living room, a fireplace in the library and a fireplace in Betty’s office, where she could study the molecular biology of bacteriophage tail fibers to her heart’s content.

Now, it’s true that it was a white elephant of a house, impossible to maintain, and that it cost $3,491 per minute to heat in the winter. But it was eminently grand and substantial, and besides, the neighborhood was full of polite children and their parents. Why, it was as if we had become grandees of Upper Mountain Avenue in Montclair. I’ll have to find some photos to show you sometime.

Also, alas, that house’s plumbing was old and quite fragile.

One day the museum-piece of a faucet in the master bathroom developed a leak. I turned off its water supply, disassembled the handle and discovered that the washer was worn to nothing. That washer was made of leather. I had never seen such a thing. Where would one find a leather washer in Gardner, Massachusetts, in 1986? A washer made of leather!

I wouldn’t hit that pipe with a hammer if I were you, Henry!

The walls in Henry Duck’s kitchen are the same color as were the walls in the little breakfast room of our house in Gardner. At the back of that room there was the cutest little closet, just about big enough to hold a broom and a mop. And in that closet were the pipes that brought water to the bathrooms on the second and third floor of our substantial house.

Our world has point and structure

As discussed, I’ve been reading Frank Kermode’s book The Sense of an Ending: Studies in the Theory of Fiction, which is full of gems like this:

Even if it were true that the forms which interest us are merely the architecture of our own cells [. . .] we should still have to make allowances for the fact that they do, after all, please us, even perhaps bless us. [. . .] Even if we prefer to find out about ourselves less by [dealing with the messy reality of our lives] than by brooding over the darkening recesses of a Piranesi prison, we feel we have found our subject and ourselves, and that for us, as for everybody else, our world has point and structure.

I promise there’s a reason I include this.

Truscott on bluestone

Back in 1969, Lucian Truscutt is still hunting for that valve to repair the leak under his sink.

On I trudged, down sidewalks made of huge slabs of Pennsylvania bluestone [. . . ] Sidewalks all over the city, in Brooklyn Heights and Prospect Park and SoHo and Greenwich Village, were made with slabs of bluestone the size of dining room tables. The bluestone, which started its life a shade of blue-black after decades of being walked on by leather-soled shoes and boots and backed over by truck tires and dropped on by all manner of wood and steel and cardboard containers, was now a dark charcoal color, almost black. The single-stepped entrances to lofts were made of bluestone, so were the loading docks . . .

The grand walkways to the Beattie mansions were made of the same blue bluestone. That stuff was quite heavy, I’ll have you know.

Oh, Henry!

To be continued. . .

To paraphrase Holland-Dozier-Holland’s Motown classic “Heat Wave” (as gloriously sung by Martha Reeves, of Martha and the Vanellas), has high blood pressure got a hold on me, or is this the way reading esoteric, denser-than-a-neutron-star literary theory’s supposed to be?

From the Olde French: “If they don’t like it, fuck ‘em.”

I’ve included the same picture of that old farmhouse in about a half-dozen of these essays so far. I’ll surely include it in future ones too. If you don’t have a clear image of it in your head and don’t feel like following the link back to an earlier post, just imagine a nice old farmhouse, just barely large enough to house five adults and seven children.

If you’re wondering if Westborough State Hospital is the inspiration for ‘Eastboro State Hospital,’ which appears in both Cheap Complex Devices and The Pains, the answer is yes.

Wonderful story and writing. Keep it up.

A bust-a-gut, for sure. My only similar experience was scouring LA for a left threaded metric mandrel armed only with the accompanying nut to prove that I wasn’t gaslighting.