I Saw a Tangerine Sun Suspended in Haze Over the Cemetery Tonight

Intimations of mortality between the 'tick' and the 'tock'

The Science of Storytelling

The introduction to Will Storr’s great book The Science of Storytelling begins with this paragraph:

We know how this ends. You’re going to die and so will everyone you love. And then there will be heat death. All the change in the universe will cease, the stars will die, and there’ll be nothing left of anything but infinite, dead, freezing void. Human life, in all its noise and hubris, will be rendered meaningless for eternity.

That’s jolly, innit?

Here’s a great photograph that I saw it in a friend’s timeline on Facebook a few weeks ago. It’s kinda jolly too, don’t you think — I mean by way of reminding us how it all ends?

The caption that Nancy gave her evocative photo has echoes of S.T. Coleridge's poem ‘Dejection: An Ode,’ which begins with a borrowed quatrain from the ‘Ballad of Sir Patrick Spence’:

Late, late yestreen I saw the new Moon, With the old Moon in her arms; And I fear, I fear, my Master dear! We shall have a deadly storm.

Coleridge’s Ode doesn’t do much for me but the ‘Ballad of Sir Patrick Spense’ is pretty cool. It tells the story of how the (unnamed) king asks who the best sailor in his (Scottish) realm is, and he’s told that Sir Patrick Spense is the man. So the king says, “Tell Spense to to to Norway and get my daughter” and so Spense goes, even though it’s the middle of winter and the weather is horrible and he knows he’ll probably die. So he goes and indeed he dies (variously on the way to or from Norway (depending on the version of the ballad). So no ‘final resting place’ in cemetery for him and his Scottish lairds. Just a common watery grave.

The Great Figure

Under Nancy’s photo on Facebook her life-partner Paul posted this picture, without comment:

Of course you recognize “The figure 5 in gold,” the 1928 painting by Charles Demuth, which you saw in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City, and you recall that that painting was given to the museum by the painter Georgia O’Keefe, who inherited it from Demuth, who died in 1935 at the young age of 51. In both Breaking Bad and its prequel/sequel Better Call Saul, Georgia O’Keefe and her paintings are a recurring trope hinting at stillness and death and the cosmic void, kind of like how a photograph of a tangerine sun suspended in haze over a cemetery hints at those things too.

But why did Paul post this reproduction of Demuth’s painting as a commentary on his good friend Nancy’s photo of a tangerine sun suspended in haze above the cemetery? This painting is quite alive! It’s the opposite of O’Keefe/Tangerine Sun! What was Paul’s point?

Oh, come on. You know why! Think!

Still stumped? Fine, I’ll explain. “I saw the figure 5 in gold” is Demuth’s visualization of ‘The Great Figure,’ the 1920 poem by William Carlos Williams:

The Great Figure

Among the rain

and lights

I saw the figure 5

in gold

on a red

firetruck

moving

tense

unheeded

to gong clangs

siren howls

and wheels rumbling

through the dark city.So, in posting the image of Demuth’s painting, Paul is using the allusion to the phrase “I saw the figure 5 in gold” to echo the cadence of Nancy’s “I saw a tangerine sun in haze.” It’s a comment on the caption to the photo, not on the photograph itself.

I saw a tangerine sun suspended in haze

I saw the figure 5 in gold(Note: Any poem that begins with the words "I saw" immediately induces autonomic recitation of the first line of Allen Ginsberg's 'HOWL': "I saw the best minds of my generation destroyed by madness, starving hysterical naked, etc” but that’s not the kind of thing we’re talking about here. I don’t know where Ginsberg is buried.)

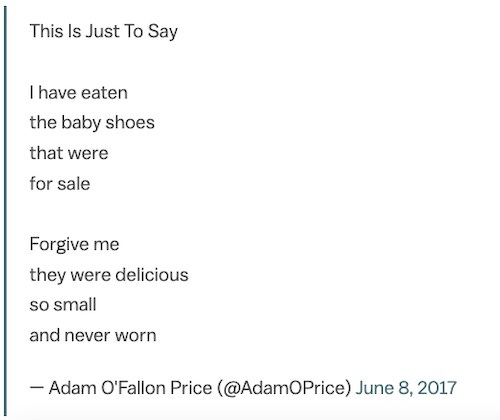

If you weren’t acquainted with Demuth’s painting or William Carlos Williams’ poem ‘The Great Figure’ before reading this edition of Sundman figures it out!, perhaps you’re more familiar with Williams’ oft-parodied poem ‘This is just to say’:

This is just to say

I have eaten

the plums

that were in

the icebox

and which

you were probably

saving

for breakfast

Forgive me

they were delicious

so sweet

and so coldBecause you live on the internet you’ve seen parodies of that poem all over the place, in particular when combined with the meme of The Six-Word Story, apocryphally attributed to Ernest Hemingway,

For sale: Baby shoes Never worn

as in this legendary tweet attributed to Adam O’Fallon Price:

But did you know that the original ‘This is just to say’ parodist was the New York poet Kenneth Koch? His ‘Variations on theme by William Carlos Williams’ was printed in his Thank You and Other Poems, published in 1962. It also appears on page 135 of The Collected Poems of Kenneth Koch. Consult your own copy and see if I’m lying! (By the way, if you’re curious about what my late friend Albert Joseph Compton Jr, looked like, he looked very much like this picture of Koch.)

Now, I confess that when I first heard that William Carlos Williams had written a poem called ‘The Great Figure’ I immediately assumed it was about that molecular biologist I met at that party in Lafayette, Indiana, in 1978. You want to talk about a great figure?!? Boy oh man. I’m not joking. What a vision she was, that first time I ever saw her, in that flowing Indian-print dress, dancing with her friend Tricia! I repeat: A vision. And honest-to-God vision. Great figure? Boy howdy. Great figure? I’m getting a bit overheated here just thinking about it. Somebody get me a glass of water!

But then I thought, No, wait! Willams wrote his poem in 1920, and the molecular biologist with the great figure wasn’t even born until 1949, so she couldn’t have been what Williams was writing about. Unless he had a time machine, of course, but that’s just silly.

Later in his introduction to The Science of Storytelling Storrs writes, citing the psychologist Jonathan Haidt,

Story is what the brain does. It is a ‘story processor,’ not a ‘logic processor’. Story emerges from human minds as naturally as breath emerges from human lips. You don’t have to be a genius to master it. You’re already doing it. Becoming better at telling stories is simply a matter of peering inwards, at the mind itself, and asking how it does it.

The sense of The Sense of an Ending

Did you ever watch a movie that gets the book it’s based on so wrong that you feel like punching a wall? I have.

Alfred Hitchcock’s Rebecca gets me a bit riled up a bit because of the tacked-on sappy ending. Daphne DuMaurier’s novel Rebecca is a love story in the way E. Allan Poe’s ‘The Fall of the House of Usher’ is a love story. Which is to say it isn’t a love story. At all. It’s a sublimely creepy tale of gothic horror. But I can forgive Hitchcock; he was working under the constraints of Hollywood. Except for the ending the rest of the movie is OK.

Stephen King evidently hated Stanley Kubrick’s movie The Shining which was based on a novel by King, but I don’t care what King thinks because I think that movie is great. It’s kind of inspirational, actually. I try to bring my Sundman figures it out! stories to you in the way Jack Torrance brings his story to his wife Wendy. Here’s Johnny!

I’m sure you can come up with a half-dozen other examples yourself of awful movies made from great books.

But whatever movies you may come up with, none them are as awful as the movie version of Julian Barnes’ novel The Sense of an Ending. That movie is so bad that it actually made me angry. It was as if the moviemakers were doing violent things to a defenseless dear friend of mine.

For what it is, Barnes’ The Sense of an Ending is a virtually perfect novel. It’s not almost perfect in the way that say, Moby Dick is almost perfect, because it’s not as ambitious as Moby Dick. It’s more of a miniature. But every word in The Sense of an Ending is there for a reason, and Barnes tantalizes the reader until the last word in the book.

The basic story, told in the first person, is of an unprepossessing man (“Tony Webster”), who, in his twilight years, receives a communication from a long ago girlfriend that has to do with a long ago friend of theirs, “Adrian,” who killed himself at a young age. As the story progresses we see Tony Webster making all kinds of incorrect assumptions both about what is going on “now” and about what went on in the past. At the end of it all he is forced to reckon with the knowledge that the story he has been telling himself about who he essentially is, is all wrong. He’s left to wonder if he’s been lying to himself his entire life.

What most torments torments Tony is the unknowability of certain things that he now desperately wants to know. Most particularly he wants to know what was in his friend Adrian’s diary. He needs to know. But the diary has been burned. It’s gone. He’ll never know what was in it. And neither will the reader of The Sense of an Ending know what was in that diary, as much as we may want to. It’s a beautifully told, compelling tale.

But there’s much more to the book than that. Because The Sense of and Ending is a work of metafiction as much as it is one of fiction. Take the title of the book, for example. What the heck does it mean? It seems so arbitrary. And yet nothing in the book is arbitrary; every little detail dropped in the opening chapters is revealed to have a deeper significance in the later chapters. It is the opposite of arbitrary. So let’s start at the very beginning. What’s going on with that title?

A Cemetery on West Chop

The cemetery under the tangerine sun in Nancy’s photo is known as Oak Grove; it’s the biggest one in Vineyard Haven, covering about five acres on a gentle slope. One entrance is opposite the playground of Tisbury Elementary School, another entrance is opposite the Tisbury Senior Center.

A mile or so away is the smaller, quainter cemetery on West Chop. Some relatively famous people are buried there, like Mike Wallace of “60 Minutes” fame and William Styron, the novelist.

Also my friend Tom Hale, a shipbuilder and storyteller who was present at the liberation of the Bergen-Belsen Concentration Camp; and Tom Gothals, a Melville scholar who — as I learned while seated next to him at a Martha’s Vineyard dinner party — no, not that party — was in the room at Bastogne where General McAuliffe pronounced “nuts!”. Gothals actually heard him say it. After the war Tom wrote a novel that grew out of his experiences in the Battle of the Bulge. He told me it wasn’t very good but I found a copy on Ebay and read it. He was right; it’s not very good. But the guy was a Melville scholar and he was in the room when McAuliffe said ‘nuts.’ That’s like having been in the boat with Washington when he crossed the Delaware. Who cares if his stinkin’ thirty-five-cent novel was any good or not.

So many stories associated with that little cemetery on West Chop. Maybe I’ll tell some of them at some point.

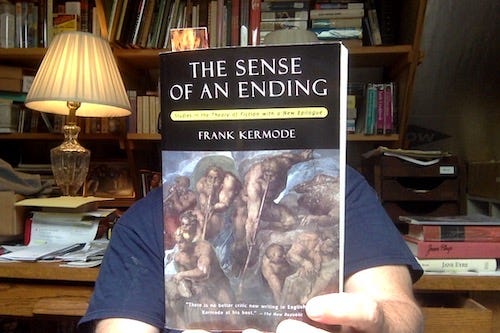

Two Senses of an Ending

We were talking about why Julian Barnes might have chosen The Sense of An Ending as the title for his little novel about memory and regret. So it’s perhaps worth noting that The Sense of an Ending is also the title of a 1966 book of literary criticism by Frank Kermode. The subtitle of Kermode’s book is Studies in the Theory of Fiction. So OK then. It appears that Mr. Barnes has just dropped a pretty big clue in our lap. Could it be that his novel is also a ‘study in the theory of fiction?’

The short answer is YES, WINNER WINNER CHICKEN DINNER!!

If you read Barnes’ book closely again you’ll find all the ways that he has manipulated you, the reader. He’s led you down the proverbial garden path. Fictions within fictions about fiction.

The overall effect, then, when you see it, is like the climax of the movie The Usual Suspects, when it’s revealed that story we’ve been watching as fact has all been improvised in real time.

[So of course in the movie version of The Sense of an Ending all ambiguity is removed, things that are unknowable by Tony Webster (or readers of Barnes’ book) are spelled out in the movie. All your nagging questions are answered. It’s like if they made a movie of Waiting For Godot, and Godot showed up in the first act.]

I went to Thriftbooks and I got myself a copy of Kermode’s book. And it’s fascinating, but I gotta tell you it ain’t exactly easy reading. His main thesis, as far as I’ve been able to make it out so far, is that all fictions, including those that we tell ourselves about who we are, have beginnings, middles, and ends.

This is something that Will Storrs says too, in his Science of Storytelling — and with scientific evidence to back him up: we all make up stories that we tell ourselves about who we are. We take the events of our past and order them into cause-and-effect sequences. In order to understand who we are and how we have become who we are, we need some conception of time, and that implies a conception of beginning-middle-end. We try to figure out what it’s all about in ways that allow us to feel good about ourselves.

That’s obviously what I’m doing in these episodic autobiographical Sundman figures it out! essays.

But it’s not just writers and and philosophers and storytellers who do this. You do it too. Everybody does it. Everybody has their own sense of their own life’s story, which implies a sense of an ending, whether explicit or not.

This is from the first page of Barnes’s Sense of an Ending:

We live in time—it holds and moulds us—but I’ve never felt I understood it very well. And I’m not referring to theories of about how it bends and doubles back, or may exist elsewhere in parallel versions. No, I mean ordinary, everyday time, which clocks and watches assure us passes regularly: tick-tock, click-clock.

Here is Kermode’s Sense of an Ending, page 44:

Let us take a very simple example, the ticking of a clock. We ask what it says: and we agree that it says tick-tock. By this fiction we humanize it, make it talk our language.

Kermode then goes on to spend about 3 pages expounding this point. After 17 more pages on other points of philosophy he comes back to tick-tock, on page 64:

Our ways of filling the interval between the tick and tock must grow more difficult and more self-critical, as well as more various; the need we continue to feel is a need of concord, and we supply it by increasingly varied fictions. They change as the reality from which we, in the middest, seek a show of satisfaction, changes; because ‘times change.’ The fictions by which we seek to find ‘what will suffice’ change also. They change because we no longer live in a world with an historical tick which will certainly be consummated by a definitive tock. And among all the other fictions, literary fictions take their place.

And thus we see, as we read the account ostensibly penned by ‘Tony Webster,’ that the stories he tells himself grow more difficult and more self-critical and various.

Thus Julian Barnes’ The Sense of An Ending is both a fictional autobiographical meditation and a deep exploration of the literary theories of Frank Kermode. It’s great fiction and it’s great metafiction. And the coolest thing about it is that it’s so deft. You can totally enjoy Barnes’ book without knowing the first thing about Kermode’s book. That kind of stuff might not give you a kick in the pants, but I love it.

Anyway, whether you like that kind of fancy-pants literary stuff or not, don’t waste your time on the movie. It will only make you stupid.

A Dream

In my dream a couple of weeks ago I was back in the corporate world, working for some Silicon Valley startup. I was in a meeting with six or eight others seated around a conference table, and I realized with a start that all of the men and women there with me were in their twenties or thirties. “Holy cow!” I thought to myself in my dream. “You’re getting old, John. You’re twenty years older than half the people in this room! You’re fifty years old, and you have no savings! In only fifteen years, if you manage to last that long in this youth-obsessed industry, you’ll be retired. You’d better get your act together. You don’t have much time. You’d better get busy!”

Then I woke up and found out I was seventy. I still don’t have any savings. Yikes. (Won’t you consider upgrading to ‘paid’? Won’t you please help me spread the word?)

You get to be my age and you start to look at cemeteries differently than you did when you were younger. When you were twenty-six, say, just back from Africa (again), and watching a woman in a print dress dancing with her friend at a party in Lafayette, Indiana. I think it’s fair to say that in those days you didn’t think about cemeteries at all.

An outstanding post, Brother Sundman! Some good poetry, some good philosiphizin'., something familiar, something peculiar, something for everyone: A comedy tonight!

Vaguely apropos, allow me to quote what may well be my favorite poem ever:

This Be The Verse

BY PHILIP LARKIN

They fuck you up, your mum and dad.

They may not mean to, but they do.

They fill you with the faults they had

And add some extra, just for you.

But they were fucked up in their turn

By fools in old-style hats and coats,

Who half the time were soppy-stern

And half at one another’s throats.

Man hands on misery to man.

It deepens like a coastal shelf.

Get out as early as you can,

And don’t have any kids yourself.

I’ll give a Just So story version. Reality isn’t Platonic or Newtonian. It’s not possible to just look around and size up a resolution of forces. Reality isn’t a collection of instantiated deterministic models. It’s a collection of signal and noise. Signals have direct salience to our present wellbeing or even existence. Noise doesn’t, except to the extent that it masks the signal. Noise can be divided into two types--interference and random variation. Interference occurs when trying tease out incoming perception that is relevant to two or more aspects of life to be able to act on the right signal. Random variation is just sound and fury signifying nothing. The task in both case depends on pattern recognition. Is that signal “take cover” or “all clear.” The a background pattern signal or noise? Because randomness is not the absence of patterns. Randomness is absolutely chock full of patterns

In our quotidian lives we are good at things such as knowing the difference between a truck backup alarm and a microwave finishing. Simple signals disambiguate into simple patterns. But other times we are surrounded by supposed signal that isn’t. The poor market technical analyst finds a market break’s explanation in a long series of daily price changes with “triple tops,” “spinning Batons” and other spurious artifacts of random walks. Randomness is full of patterns.

So, we bumble through our lives with imperfect information and heuristics. Our analogue minds wrestle with intractable digital problems. Our digital minds wrestle with intractable analogue problems. All things considered, it no wonder we fool ourselves so often.