All-star break

Watching baseball with my grandmother and her sister in 1961

Précis

During the 2024 ‘All-Star break,’ when Major League Baseball teams have no regular games scheduled for four whole days and play just one ‘All-Star’ game on Tuesday, July 16, I’m taking a break from the overwhelming news of the day to reminisce about the All-Star games of my childhood, when my brother Mike and I would travel all the way from North Caldwell, N.J. to West Orange, a distance of seven miles, to watch the game on a black and white TV with my Scottish grandmother, Grandma, who understood nothing about the game, and her sister my Aunt Mary, who was a passionate fan. I vector from there into all kinds of spaces, including observations on grandparenthood as viewed from both directions, and a New Year’s Eve party in Greenwich Village 1976-77 when a fight nearly broke out between the gay disco-loving faction and the straights who preferred rockaroll.

A Grandma meet-cute

I met Grandma for the first time in 1957, when I was four years old, as she disembarked from the Queen Mary onto a Manhattan quay. The last time my mother had seen her own mother before then was in 1948 when she left Scotland for America by way of a steamer out of Liverpool. My brother Mike, one year older than me, was with us. I don’t remember if my sisters Maureen, who would have been 3, or Barbara, 1, were with us. Maybe they were home, with Nana — my other grandmother, the Irish one. My father was at work. There was great crowd of people there on the quay by the gangplank, like in one of those movies about when people were much more likely to cross the Atlantic Ocean on a ship than in an aeroplane — “An Affair to Remember,” say, staring Carry Grant and Debora Kerr. I can’t say for certain what the first words were that I ever heard Grandma say, but I expect they were something like ‘Och, the wee bairns!1”

The American League and the National League in 1961

In those days there were only two occasions on which players from the American League faced players from the National League: The World Series at the end of the season, and the All Star Game, in July. There was no inter-league play. Except for the All-Star game and the World Series, the American League and the National League might just as well have played on different planets.

There was no such thing as a ‘designated hitter’ in 1961. Pitchers — who were typically very poor hitters — took their turns at the plate like everybody else. This provided for dramas of various kinds. Such as when one pitcher threw a fastball directly at the opposing pitcher, intending to hit him, resulting in a big melee involving all the players of both teams — the sort of brawl more appropriate to NHL hockey as it was played in the 1960’s (“I went to a fight last night and a hockey game broke out”) than to the dignified sport of baseball.

There were no playoffs, either. It was a simple race. The team with the best win/loss record in each league went to the World Series.

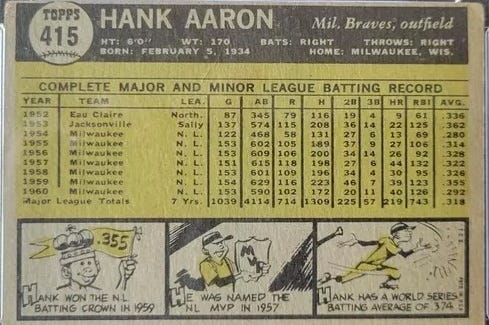

Television mostly only played games of the local team, and color TV was almost a decade in the future in my house. Like most of my friends, I had a collection of baseball cards; that was where I got most of my information about non-Yankee players.

Because of all these factors the All-Star game was a much bigger deal in those days than it is today. Something more like the Olympics or the World Baseball Classic, in which teams actually try to win. The 1961 American League roster included names like Mickey Mantle, Roger Maris, Yogi Berra and Harmon Killebrew. The National League had Hank Aaron, Roberto Clemente, Sandy Koufax and Willie Mays. For nine-year old me, this game was a high point of the entire summer vacation.

Franklin Avenue in West Orange

Here are some screencaps that I grabbed today from Google Earth of the houses at 130 and 134 Franklin Avenue in West Orange, and of Colgate Field, a baseball diamond directly across the street from #130. The only things that have changed since 1961 are the makes of the cars on Franklin Avenue and the colors of some of the houses. And also Colgate Field seems a lot smaller to me now than it did when I was nine and the teenagers who played there seemed like giants.

See the top floor of #130? That’s where Grandma lived, along with Uncle John, my mother’s younger brother, in a two-room, 1-bath apartment. The front room, which had two beds that doubled as couches, was a living room by day and a bedroom by night. From the windows in the front room you could look out on Colgate Field, where baseball was sometimes being played, whether organized or sandlot.

I remember visiting Grandma and Uncle John with my parents and five or six brothers and sisters. Sometimes one of my mother’s brothers or sisters would be there too, with spouse and their children, my cousins. You’d be amazed how many people you could cram into that tiny walkup.

Two houses down the street lived Aunt Mary. She had her own home, with a front porch and a living room and a dining room and a kitchen and an upstairs with her bedroom and a guest room. Behind the house was a small but grand-looking carriage house. You might have called that building behind her house a “garage” or even a “big shed,” but to Aunt Mary it was a carriage house. Aunt Mary was grand, in her own way.

Until she got too old, my family used to have Easter Sunday dinner at Aunt Mary’s house. I remember sitting at her table, about five years old, dressed in my most uncomfortable best clothes, waiting for the ham and homemade dinner rolls to be brought out of the kitchen. Aunt Mary was a stickler for proper manners. “This is the way the porridge goes,” she would say, passing each platter clockwise around the table.

I don’t know when Aunt Mary came to the States from Scotland, but it was well before my mother or Grandma did. Aunt Mary was a lot more American than her much later-arriving sister.

My mother was the oldest of Grandma’s five children. I don’t know the order in which Grandma, John, Tom, Ellen and Rita emigrated to America. But my mother, Margaret Mary McFall, was the first of them.

Wait, how did this happen?

Race tracks in the days before cell phones

It is hard for you children to conceive, but in the days before cell phones, if you went to a race track to watch the horses go, you would find all the pay phones locked with padlocks from the beginning of the first race to the end of the 9th, and last, race. Presumably this was done to prevent people from calling their bookies from the track. Gambling was legal if you bet at the track, you see, but placing bets with a bookie was not.

Grandfathers

My mother came to America from Scotland, by herself, age 22 or so, a few years after the conclusion of the Second World War, with all of her worldly possessions in a Cunard Line steamer trunk.

The movie Brooklyn tells a story that very closely parallels my mother’s. The young protagonist of that movie, Eilis, upon her arrival from Ireland, lodged in a rooming house for young Catholic women in Brooklyn. The Catholic girls’ rooming house in which my mother stayed when she arrived from Scotland was in Ocean Grove, New Jersey. Not Brooklyn, but close enough. In the movie, Eilis meets and marries a young Italian-American man. My mother met and married my father, a Finno-Irish American. In the movie, a homesick Eilis is drawn back to Ireland by the death of her sister. My homesick mother was nearly drawn back to Scotland upon learning that her father was dying of cancer. She was tempted to return to Scotland, just as Eilis was tempted to return to Ireland, but she did not go.

The story of why she did not go back to Scotland is quite dramatic and very moving. I only learned it a few years ago, when my brother Mike reported on the contents of some letters that he had found in my parents’ effects. Maybe I’ll tell that story some day.

But the net result to me was that I only had one grandfather when I was growing up. I was not aware of my maternal grandfather’s absence any more than you’re aware of your inability to see ultraviolet light the way hummingbirds do.

Pop, my father’s father, was a very big presence in my young life. The essay below tells of how Pop came to America as a penniless refugee, and of how he close he came to attempting to swim from Ellis Island to New Jersey — he would almost certainly have drowned had he done so — before an angel disguised as a Swedish-American sponsor intervened.

Pop retired from the garage in Newark when I was about 12. One day, as I was sitting in his living room reading one section of the Newark Evening News while Nana was reading another, Pop, retired, reclining back in his Easy Boy chair, said to me in his Swede-Finn accent, “Now Johnny, you explain to me what it is, this baseball.” So I taught him about baseball.

A lone figure skis across a frozen sea, pursued by Russians shooting guns

Fishing on the Palace II, Party Boat Out of Hoboken Sometime around 1960, when I was about eight years old, my grandfather, “Pop,” first took me fishing. The night before our planned excursion we went to the chicken coop and got some empty burlap bags that smelled of corn meal and oyster shells and put them in the trunk of Pop’s car along with his fishing…

And now I am a grandfather. I wonder at all the things my grandchildren will teach me.

My Brooklyn connection

After the first time I came home from Africa and Anne broke off our engagement saying, “I’m going to play with Jane,” I had the most remarkable chance encounter with another woman — we can call her Eleanor — whom I had known in college. Eleanor lived in Park Slope, Brooklyn, quite near Polhemus Place and Fiske Place.

You’ve seen those streets. Every movie ever made that features a scene of Old Brooklyn with its classic brownstones — including Brooklyn — was filmed on one of those streets — both because they have the great-looking buildings, and because they’re very short streets — look ‘em up! — so if you need to close off traffic and put old cars on the street and fill the sidewalks with ‘extras’ wearing antique clothes in order to shoot your movie, the number of people you’ll be inconveniencing is manageable.

Eleanor and I dated a bit starting in late spring of 1976, the year before I started grad school at Purdue, the place where I met the molecular biologist with the great figure that you’ve heard me mention before.

On December 31, 1976, Eleanor and I had a date to go to a New Year’s Eve party in Greenwich Village, in Manhattan. I was going to meet her at her place in Brooklyn in the late afternoon, and from there we would travel by subway to the Village. We agreed that I would call her sometime around 2 PM that day to finalize our plans.

Uncle John

Uncle John was a man of modest ambition who knew what pleased him. He had strong political views — he was quite leftist, and fervently anti-Republican — but he never became a U.S. citizen, so he never voted. Uncle John got his first driver’s license when he was about 40 and spent his entire working life making light bulbs at a light-bulb factory in Bloomfield, where he was a shop steward in his union. He loved golf and opera and country music and watching the ponies run and bowling with his seventeen nieces and nephews, upon whom he doted.

Unlike my mother and Aunt Ellen and Aunt Rita and Uncles Bill and Tom, whose Scottish accents became less pronounced as the decades rolled on, Uncle John’s accent, if anything, seemed to get stronger. After 1975 his favorite movie was The Magic Flute; I don’t know what his favorite movie was before then. You might not expect a light-bulb factory worker — who didn’t get a driver’s license or his own apartment (the first floor of #130 Franklin Avenue) until he was more than forty years old — to buy a season ticket to the Metropolitan Opera in New York City every year. But then, you didn’t know my uncle John.

Once Uncle John got his own apartment he could play his records anytime he liked. He had one of those record players on which you could stack a bunch of LPs that would drop the next record automatically when the preceding record had finished playing. Audiophiles recoiled in horror at the very ideas of dropping one record on top of another like that, but Uncle John didn’t care. He’d stack up Loretta Lynn and Conway Twitty on top of Leontyne Price singing Aida and Beverly Sills in Donizetti's Lucia di Lammermoor and be as happy as a person can be.

But baseball? “Och! It’s just a bastardized cricket!” said Uncle John.

Aunt Mary and the Red Sox

Aunt Mary’s last name was Thompson. That must have been her married name, because Grandma’s maiden name was Connor (my Grandma, née Sarah Connor, had a lot in common with her namesake, played by Linda Hamilton in the Terminator movies). So that seems to imply the existence of a Mr. Thompson, who would have been my uncle. But no such person was ever mentioned or hinted at. I do have the vaguest memories of the words “New Hampshire” coming up from time to time in connection with Aunt Mary, but that’s as much as I have.

However it may have come about, Aunt Mary had an abiding passion for the Boston Red Sox. So much so that she regularly sent birthday and Christmas cards to several of the players on that team, and a few of them even reciprocated. Aunt Mary would sometimes show those cards to me, but the names on them meant little to me; I mostly only followed the Yankees, Dodgers and (Mike’s favorite team) the Cardinals.

Pop and the Mets

Pop developed an interest in baseball in the year that the New York Mets came into existence as an expansion team. This was after we had sold the farmhouse at 31 Grandview Ave in North Caldwell and moved into the new house that my father built at 93 Grandview, with assistance from Pop, Uncle Harry and Mike and me. At 93, to go into Nana and Pop’s apartment I usually went by way of the back porch, to which my parents’ part of the house connected with two doors: one door to the kitchen, one to the living room.

My father was a TV snob. He called TV ‘the idiot box,’ and the only channel he watched was PBS, and that very seldom. There was no television in the living room of our house at 93 Grandview Avenue, of course. To watch TV you had to go to the windowless room in the basement. Dad liked baseball enough to be the coach of the little league team that Mike and I played on, but he never watched a game on TV.

Pop and I, however, watched many Mets games on the TV in his living room, from 1962 until 1970, the year I went off to college. Pop’s understanding and love of the game grew every year, from 1962, when the Mets went 40–120 and finished tenth and last in the National League, 60+1⁄2 games behind the NL Champion San Francisco Giants, to 1969, the year the Miracle Mets won the World Series.

I taught my grandfather to love baseball. I’m pretty proud of that. (I’m still working on my wife.)

Game night and cribbage

I don’t remember how many times Mike and I went to West Orange to watch the All-Star game with Grandma and Aunt Mary. It was at least twice, maybe three or even four times.

Mom would drop us off around dinner time the night of the game and pick us up sometime the next day. I always felt completely at ease with Grandma, but Aunt Mary made me a bit nervous, as she was quite particular about manners and comportment. I was never quite relaxed in her house, but I still liked it.

On All-Star day, as game time approached Grandma would arrive from her house two doors away. Four chairs would be placed facing the black and white TV in Aunt Mary’s living room. A little table would be set up, and a cribbage board and a deck of cards would be placed upon it.

And then the four of us would watch the game, while desultory playing cribbage during breaks in the game when commercials were on.

I remember nervously going to bed after the games in the upstairs guest room. I remember the layout of Aunt Mary’s kitchen, and the little cupboard where she kept the birthday and Christmas cards that Red Sox players had sent her. I remember the pattern of the wallpaper in the upstairs bathroom.

About the All-Star games themselves I remember nothing at all.

New Year’s Eve, 1976: the sun goes over the yardarm

My original plan had been to take the bus from Little Falls into New York, but when Mom told me of her plans to visit her mother later that morning, I said that I would go with her to say hello to Grandma and Uncle John before I went to New York. (Aunt Mary had departed this mortal coil by then.)

Soon after we arrived in Grandma’s 3rd-floor flat, about 11:00 AM, Grandma told me that she couldn’t offer me beer before the sun went over the yardarm — noon, in other words — but she could offer me a can of sour milk. Whereupon she produced a Schlitz tallboy from her refrigerator and placed it in my hands.

Down on Franklin Ave I saw Uncle John walking on the sidewalk. Grandma looked out the window and said “It’s no far he’ll be going. He has nay a hat on his head!”

This was what I imagined Scotland was like: people drinking cans of sour milk that magically turned into beer as the sun went over the yardarm; people making observations like “It’s no far he’ll be going, he has nay a hat on his head!”

A little while later, Uncle John arrived. “Johnny my boy,” says he. “Let’s you and I go to see the ponies run.”

I explained to Uncle John that as much as I would have loved to go to the racetrack with him that New Year’s afternoon, I had a date planned with my friend Eleanor. The following conversation then ensued:

Uncle John: Call her and tell her you'll be a little late. We'll watch one or two races, and you can catch a bus from there to the city. The busses run all the time. It's just fifteen minutes! Come on! We'll have fun. Me: Well, alright, I'll call her. But I'm only going to stay for the first one or two races.

So at the appointed time I called Eleanor using Grandma’s phone, but she didn’t answer. Fifteen minutes later I called again. Still no answer.

“Come on,” says Uncle John. “We don’t want to miss the first race. You can call her from Meadowlands.”

So I kissed my mother and Grandma goodbye, and Uncle John and I hopped into his Studebaker Hawk and off we went.

When we got to the racetrack everybody passing through the gate was handed a slip good for one $2 bet on the Daily Double — the second race, and the seventh. I was just going to use my slip to bet on two horses based on their names, but Uncle John bought a racing form and insisted that I consult it before choosing my horses and making my bet. So I consulted the racing form and made a most scientifically informed choice: horse #2 in the first race of the Daily Double, and horse #10 in the second.

I went to the window and placed my bet and then went to call Eleanor to tell her about the slight change in plans, but just then the bell sounded at the start of the first race of the day and I saw the employees of Meadowlands locking up the phones. Until then I had no idea that that was done.

So, I rejoined Uncle John, who had meanwhile busied himself getting a large beer for me — it was now after noon, so no more sour milk — and we got ready to watch the next race — the second race of the day, and the first race of the Daily Double.

And don’t you know it, horse #2, my horse, won that race. So now, of course, I had to stick around for the seventh race. What choice did I have?

Uncle John made a few wagers on the intervening races, but I didn’t. I did however consume another beer or two.

So the seventh race finally arrives, and whaddaya know but horse #10 wins it. I have won the daily double, yielding $110 on a two dollar bet, and I didn’t even put up the two dollars.

I go to the window to collect my $110.

Now, according to the internet, $100 in 1976 dollars is equivalent in purchasing power to about $552.15 today, and I had won $110. So let’s say I was up about $600 because I had let Uncle John talk me into going to the racetrack with him. I was feeling pretty good about that. So I drank another beer while waiting for the last 2 races to be over and the padlocks would be removed from the phones.

Finally I was able to call Eleanor, and she answered. I expect she was a bit miffed but I don’t remember. I said, “I’m late, and I’m drunk, but I’ve got a pocketful of money and I’m going to spend it all on you!”

I took a bus into Manhattan, then a train to Brooklyn and that evening before going to the party at which there later was nearly an altercation between some hotheads about the choice of music to be played on the record machine Eleanor and I had a swell time in Greenwich Village. But no time to talk about that now!

If you watch the All-Star game tonight, I hope you enjoy it. I might even tune in myself.

Cheerio!

“Oh, the darling babies!”

You tell the best stories, John.

Throughly enjoyed this John 😂😌