A lone figure skis across a frozen sea, pursued by Russians shooting guns

How my grandfather left Finland and came to America

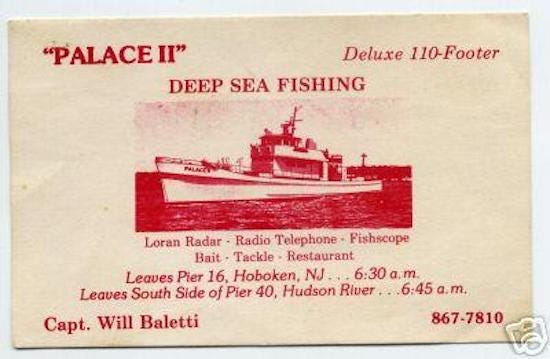

Fishing on the Palace II, Party Boat Out of Hoboken

Sometime around 1960, when I was about eight years old, my grandfather, “Pop,” first took me fishing.

The night before our planned excursion we went to the chicken coop and got some empty burlap bags that smelled of corn meal and oyster shells and put them in the trunk of Pop’s car along with his fishing rod and tackle box. At five the next morning, while it was still dark outside, Pop came into the room I shared with my brother Mike — the little room downstairs next to the entrance to Nana and Pop’s apartment that had been Uncle Harry’s room until he went into the Marines — and told us to get dressed and come into his kitchen for breakfast. I was too excited to eat, but Pop placidly sat and ate his bowl of Kelloggs Corn Flakes while I fretted that we would miss the boat.

We went on the Palace II, a repurposed WW II ‘sub chaser’ that sailed out of Hoboken, New Jersey, directly across the Hudson River from the Empire State Building. Palace II left the dock at precisely 6:30, bound for the fishing grounds off Point Pleasant, New Jersey, three hours away. It returned to the dock at 4 in the afternoon, by which time our two burlap bags were full of ling cod, sea bass, porgies and tautog.

We went fishing three or four times every summer until I was about 12. After a few such trips Mike decided that fishing wasn’t for him, so after that it was just Pop and me. At some point Pop figured out that like a little kid on Christmas Eve, on the eve of a fishing expedition I was too excited to sleep, so he stopped telling me about our trips in advance.

A few times each summer he would enter the darkened room where I was deep asleep and say, in his Swede-Finn accent, “Wake up, Yonny. We’re going fishing!”

The Widow Nelson

We lived in the at 31 Grandview Avenue then, before the town took the farm by eminent domain to put West Essex High School on it. Mrs Nelson’s house was on Greenbrook Avenue at the corner of Woodland, a ten minute walk away, right next to Dr. McCarthy’s house, where I got my teeth ground and cavities filled. To my parents, Mrs Nelson was always Mrs Nelson, but to Pop she was ‘the widow Nelson,’ and Mike and I were her conscripted helpers. “The Widow Nelson’s grass is getting long. You boys go mow it,” Pop would say. Or in the winter after a snowstorm, “Take your shovels and go do Widow Nelson’s driveway.”

When I say that we were conscripted I don’t mean that it was a regular thing. This only happened a few times. But when Pop told us to do something, we did it. I don’t remember anything about Mrs Nelson herself, only that Pop watched out for her. I’m sure he did many more chores around her house than Mike and I ever did.

An Upper Mountain Avenue meet cute

In the early years of the twentieth century, Upper Montclair, New Jersey became a fancy address for the newly wealthy swells of New York. Upper Mountain Avenue in Upper Montclair was the fanciest address of all, where show-offy mansions that afforded views of the Manhattan skyline fifteen miles away competed in opulence.

Every house, of course, had to have a garage to house its several motorcars, which necessitated having a chauffeur on staff to maintain and drive those newfangled contraptions. One such house had a tall handsome Swede-Finn chauffeur, only a few years in America but already quite conversant in English.

A nanny for the young ones was also de rigueur on Upper Mountain Avenue. This particular house had a nanny named Lilian, from Ireland, herself a recent arrival to these shores.

So that was the setting for the meet-cute of Nana and Pop, a real Upstairs/Downstairs servant-class romance. I don’t remember the name of the family they worked for (until Pop started his own garage). I do remember Nana telling me, many years later, in her thick County Roscommon brogue, “Johnny, that man was a millanaire!” I think Nana was somewhat awed by wealthy people. Pop certainly wasn’t.

Ellis Island

After crossing the Hudson to pick up a few customers from a dock in lower Manhattan, the Palace II headed for The Narrows, high above which the Verrazzano-Narrows bridge was being constructed, and thence to the Atlantic Ocean.

One day, when I was about ten years old, as we sailed by an island full of falling down buildings with broken windows and trees growing through their roofs, Pop began pointing out the various buildings to me:

“That one over there, that’s the main sorting building where you go in when you get off the boat. That one’s the boys’ dormitory; the one behind it is for the girls and women. That’s the infirmary where you go when you’re sick, and that one there’s the jail they put you in if they find out you’re no good.”

I don’t know if he used the words “Ellis Island,” but if he had they wouldn’t have meant anything to me.

“That point right there,” Pop said. “That’s the closest part to New Jersey. It’s one half-mile across.”

And then he said something that meant nothing to me at the time. I understood the words, but I was too young even remotely understand what they signified. But I grew up. I understand now.

A hitchhiker on the way to and from the junkyard

In the 1920’s Pop opened a garage in Caldwell, but he lost it in the Great Depression. By that time my father had come along as well as my Aunt Marie, and hard times had come. But by 1952, when I was born, Pop was the chief mechanic at Northern New Jersey Oil Company in Newark, charged with maintaining a fleet of oil delivery trucks.

Pop also had a side business doing automobile repairs in our barn on weekends. Sometimes when he needed a spare part — a distributor, say, for a 1949 Packard — he would go to the local junk yard and harvest one from a dead car. And sometimes I went along with him for the ride.

And so it was that as we were coming up Grandview Avenue from Singac on our way back from the dead car lot that Pop pulled over next to a guy who was walking along the side of the road. The guy leaned over and looked through the open window past me to Pop.

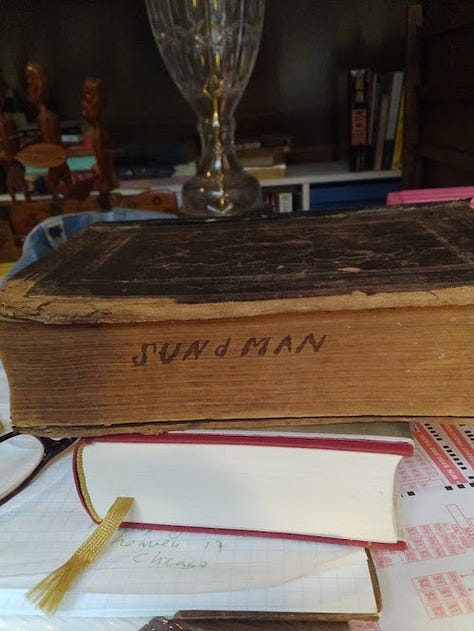

Pop: I saw you half an hour ago when I was going the other way. Why don’t you put your thumb out and hitch a ride? Guy: If I put my thumb out, my thumb is black. Who is going to stop for that? Pop: John Sundman, that's who's gonna stop. Come on, get in. I give you a ride. [The guy gets in the back seat. I expect that he was quite apprehensive.] Pop: Where you headed? Guy; Bloomfield. But if you can just. . . [Bloomfield was about a half-hour away.] Pop: I said I give you a ride; I give you a ride. (To me) Well Yonny, looks like we're going to Bloomfield.

We gave the guy a ride to Bloomfield. We’ll come back to this.

A betrayal, Reinhold Sundman’s epic flight to America, a baptism

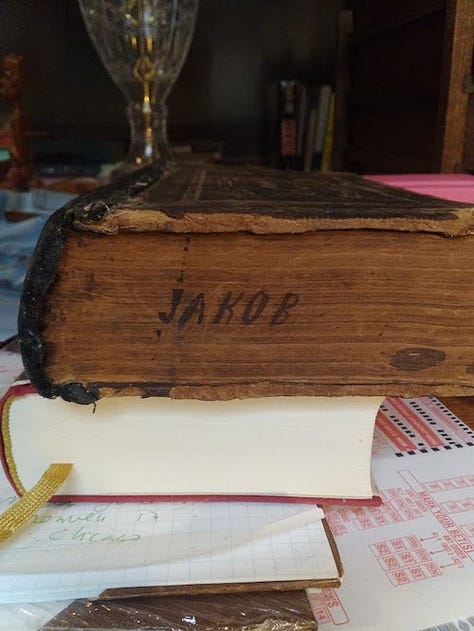

I’m not sure of the exact date when these events transpired. It was around 1915, when Pop (Jakob Reinhold Sundman, who then went by his middle name) would have been 16 or 17 years old. This was a time when Finland was part of the Russian Empire, and Finnish nationalism was strong and growing (Finland would declare its independence from Russia in 1917).

In the village of Monäs, Pohjanmaa, Lansi-Suomi, Finland, Reinhold was a member of a small underground group opposed to the Russian occupation. I expect this group was associated with the Finnoman movement, but that’s just conjecture; I don’t know anything about the group’s activities. Here’s the Finnoman motto, according to wikipedia:

Swedes we are no more; Russians we cannot become; Therefore Finns we must be.

But evidently someone betrayed them, for one night Russians showed up in Monäs, rounded up the members they could find, and executed them. Reinhold escaped capture by hiding in a grain crib, where he stayed for two days. Then, by moonlight, literally when the coast was clear, with a knapsack on his back and skis on his feet he set out across the frozen Bay of Bothnia. The keeper of a nearby lighthouse stopped the spinning light so that, for a few hours, it pointed west to Sweden.

Russians gave chase when they saw him and even got close enough to shoot at him, but Reinhold was a champion skier and was certainly more motivated than they were. He made it to Sweden.

There, somehow, he got a spot on a steamer for America, earning his passage by working in the engine room. On Ellis Island for obscure reasons (possibly because he had no identification papers at all) he was detained for nine days, on the understanding that if nobody would vouch for him he would be deported on the tenth.

But at the last moment a Swedish American man arrived and stood up for him. I have no idea how those two people learned of each other’s existence.

The man gave him a place to stay, taught him his first words of English, and arranged for him to get his first job in America: as a janitor sweeping the halls of Montclair Academy.

Thus Reinhold was granted legal entry to the USA, where eventually he became an American citizen and a fierce American patriot. An immigration official gave him his new identity papers at Ellis Island with the baptismal words “Welcome to America, kid. From now on your name is John.”

And John’s angel, the man who arrived when the last tiny bit of Reinhold’s hope was almost gone, and John was yet to be? That man’s name was Mister Nelson.

I know this story sounds too contrived to possibly be true, so below I’ll tell you how it has been verified.

Two kids in Ukraine

I knew that at some point n Sundman figures it out! I would share with you this family legend. When I saw the story about Tigran Ohandesyan and Mykyta Khanganov, two teenagers murdered in in Ukraine by Russian occupiers for resisting the Russian occupation, I knew the time for this story had come.

In their faces I see the faces of my grandfather’s boyhood friends, murdered in Monäs, Finland more than one hundred years ago in the name of the same Russian imperialism we see in Ukraine today.

Reality, Legend, Myth

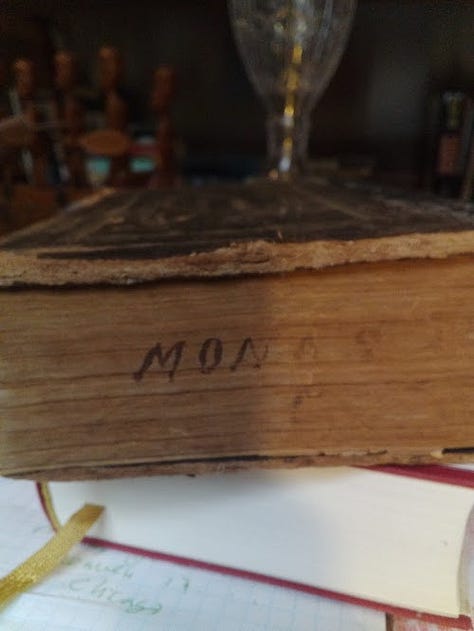

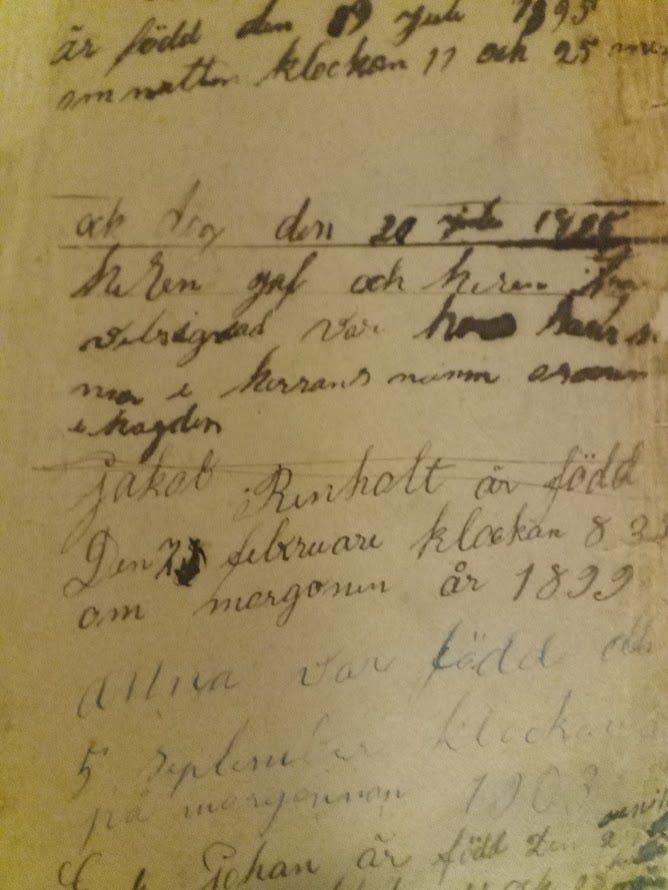

Pop eventually got back to Finland in the 1930’s to say farewell to his mother, whose name was Sana Laena. Upon his return to America he brought back with him a few keepsakes, including his baby blanket (which my father later had professionally restored and framed) and the family bible, which I now have.

Pop died in 1974. (It was on the very day that I first saw the village of Fanaye, Senegal. I have a story about that, but not for today.)

Sometime in the 1970’s my father made his “Roots tour”to Monäs. He connected with cousins, saw the house his father had been raised in and the cemetery where Pop’s mother and father were laid to rest.

And he was shown the corn crib where young Reinhold had hidden, and the place where he stepped onto the ice, and the lighthouse that had been stopped. This was sixty years after those events had transpired, but the people of Monäs had not forgotten. The most important part of the story was confirmed

As for the Mr. Nelson part of the story, I don’t know if that’s true or if I confabulated it. There’s no way to find out now. I do know that Pop had my brother Michael and me do chores for Mrs. Nelson, and I do know that somebody got Reinhold off Ellis Island and gave him his start in America. I know that that John’s first job was sweeping floors at the fancy private school where the mansion-dwellers of Upper Montclair sent their sons to be formed. I choose to believe that Mr. Nelson was Reinhold’s mysterious benefactor. It doesn’t matter if he wasn’t. The story of how Reinhold fled to America where he became John is a universal story of a refugee coming to America. Every single such story has true elements that sound contrived. The ensemble of these stories form an essential myth.

There are many American myths, and some of them are deeply ugly. But the myth of the refugee — tired, poor, homeless, tempest-tossed, yearning to breathe free — finding a welcome and a new hope here, a country dedicated to the proposition that all people are created equal — whether at Ellis Island in in New York or at the southern border or at Angel Island in the San Francisco Bay, or even on Martha’s Vineyard —this is the American myth that I claim as my true heritage.

A long way to swim

As we stood at the rail of the Palace II, sailing past the ruined buildings of Ellis Island — me, an uncomprehending ten year old thinking about fishing and Pop, a sixty-something established American man with a house and a wife and two children and twelve grandchildren and a reputation as a decent man — John surely saw the scared 17 year old Reinhold standing on the western edge of Ellis Island on his ninth day, preparing himself to swim for New Jersey the next day, knowing he very likely would not make it.

“That point right there,” Pop said. “That’s the closest part to New Jersey. It’s one half-mile across. And Johnny, don’t that look like a long way to swim.”

That’s what America meant to Pop: the ideal that he kept in his heart. The place worth risking everything — everything! — to swim for. That ideal America is what made him a passionate supporter of equality for all. It’s what made him stop for the guy walking from Singac to Bloomfield.

Pop was a complicated man and I have many stories to tell about him — most, but not all of them complimentary. But today I’m thinking mostly about his coming to America.

I post this note on the Fourth of July. In honor of Pop, and Nana, and my mother Margaret McFall Sundman, an immigrant from Scotland, and in honor of every other immigrant to this country, whether they came here penniless or rich, free or enslaved, for this one day I will try to set aside my misgivings about all that is wrong with this country and reflect on the ideal.

John Reinhold Sundman, July 4, 2023

A very cool story, and it reinforces my opinion on how tough the Finns are.

Just came across your story. Brilliantly written. A journey across the world and at that time, your pop was one tough fella.