Famous Author Teaser

October 2023 is the target date for Sundman’s Big Splash(TM), parts A,B,C:

A) Re-releases of:

Acts of the Apostles, with a new introduction by Cory Doctorow;

Biodigital, new introduction by John Biggs;

Cheap Complex Devices, new introduction by David Weinberger;

The Pains, new introduction by Ken Macleod;

B) New novel Mountain of Devils, the prequel to both Acts of the Apostles and Biodigital;

C) Spanish language editions of Acts, Biodigital, CCD and Pains.

My next Sundman figures it out! post, coming real soon now, will have a lot more info about this.

Reminder: As part of the Big Splash, founding members of Sundman figures it out! will receive print copies of all five books, autographed by me.

Uprooted

Ande, my friend from childhood mentioned in Fire Engine Memory Science, has been privately urging me to quit going on so much about firefighting and computer stuff in these stories and write instead about what it was like for me

— having grown up on a small farm where I learned to milk a cow; shovel shit out of cow sheds & chicken coops; weed a garden; harvest apples & make cider; pick and preserve peaches, plums & pears; eat grapes off the vine near the pasture; candle eggs, butcher a chicken and prepare it for cooking (removing head & feet with a hatchet, plucking the feathers, removing the viscera), drive a tractor; and make ice cream in a hand-cranked ice cream maker from Cow Beauty’s own cream and strawberries, raspberries & peaches picked for that purpose; where, from first grade through eighth, I walked to public school through woods and fields in every weather —

to find myself at 13 attending Catholic, boys-only Xavier High School in Manhattan, more than an hour away, {by {car | bus | train}, and subway} from the cows, sheep, chickens gardens and fruit trees of my yoot — and from the kids, like Ande, that I had grown up with.

Ande’s point, I think, is that everybody goes through big changes as they move from childhood through adolescence to (one hopes) adulthood, and these formative changes persist. So if you want to write an “autobiographical meditation” that has a legit foundation, you need to you need to deal with things like Catholicism and Human Sexual Response, not to mention high school, earlier than later.

Or else he has some other point, but no matter.

Xavier was not only Catholic, urban, and with an all male student body & a 99% male faculty, it was also a military school, with compulsory participation in the junior ROTC, the U.S. Army-sanctioned Reserve Officer Training Corps. Yes, that’s right, I, an awkward teen, wore a military uniform on the subways of New York, for four solid years, July 1966 to June, 1970, as the war in Vietnam got hotter and hotter and the hippie/antiwar counter culture took root everywhere — everywhere except 30 West 16th Street, that is.

But Xavier wasn’t and isn’t just a Catholic high school, it’s Jesuit. When you get your Catholicism from Jesuits, you get the hardcore shit.

A question about Human Sexual Response at Sun Microsystems

It was 1987; I was manager of a small but quickly growing technical publications group in the Massachusetts outpost of Sun Microsystems, the new darling of Silicon Valley. In a small conference room, Casey, a candidate for a technical writing position, sat before me, having completed two grueling rounds of interviews, (which, despite a two-year gap in her resume, she had aced, although she didn’t know that yet). Also in the room: Barbara, the rep from Human Resources.

Me: We're done with interviews; I'll get back to you in a few days with our decision. Do you have any last questions for me? Casey: No. I just want to say I'm really excited about the possibility of working here. Me: Well, I have a question for you. Casey: Yes? Me: [**dramatic pause**] Casey, what does SEX mean to you? HR: [**gasp!!**] Casey: [long awkward pause. Then a light goes on and she says, quizzically,] The band? Do you know the band? Me: I love the band! HR: Will somebody please tell me what's going on here before I have a heart attack?

I was an altar boy of the Latin mass

The parish of Notre Dame, in North Caldwell, was founded in 1962 when I was 10 years old. The church building wasn’t built until 1965. For the three years between the creation of the parish and the consecration of the new, modern, church building, weekday mass was said in the walk-in basement of Fr. Murphy’s rectory, a house on Mountain Avenue across the street from Gould Avenue School, and Sunday mass was said in the auditorium of West Essex High School, built on land taken from my family by eminent domain.

Before 1962 my family went to church every Sunday at St. Aloysius, in Caldwell, an old-fashioned church with a baroque altar and stands of candles in little red jars before statues of saints, the church in which my father had been baptized when he was an infant. My father used to do his impression of the parish priest when he was growing up — an Irishman who evidently had little love for his Italian-American parishioners: “Next soonday is pahm soonday and all the once-a-year guineas will be here to get their pahms. So if you want to get a seat you regular folk better get here airly.”

After dutiful instruction by habit-wearing nuns, I made my first confession at St. Al’s and then my First Holy Communion, wearing a white suit with white shoes on my feet. I learned my Baltimore Catechism at Sunday school for an hour after mass every week.

My parents weren’t hardcore Catholic, they were just Catholic. On Saturday evenings we went to Confession, and after that we didn’t eat anything until after mass the next morning. Every Saturday night before going to bed we set out clothes for the next morning, and after we seven children were asleep, my father polished all of our shoes.

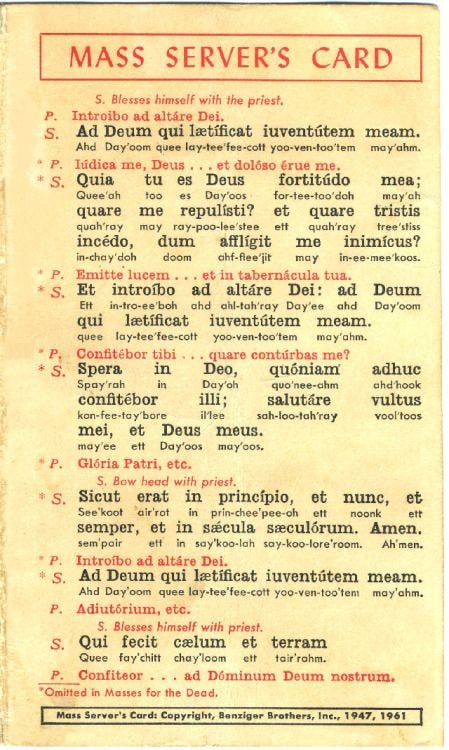

Somehow or other I became an altar boy when I was about ten years old. Mass was said in Latin; I was supposed to have memorized all my responses but never did. Fortunately I had a laminated card to cheat from.

The daily mass in the rectory basement was said at 6 AM; I was a server there about once a week. Often the only people in attendance were me, the priest, and Mr. Byrne, my 5th grade teacher. Sometimes it was just me and the priest.

A big discovery at a garage in Newark

Until my father built the new house a quarter-mile up Grandview Avenue, eleven of us lived in the farmhouse: me, my parents, my six brothers and sisters, and Nana and Pop, my father’s parents. Ten of us were Catholic. Nana, an immigrant from County Roscommon, was old-school Irish Catholic; Pop, an immigrant from Finland, was nothing (until his conversion to Catholicism when he was 65, but that’s another story).

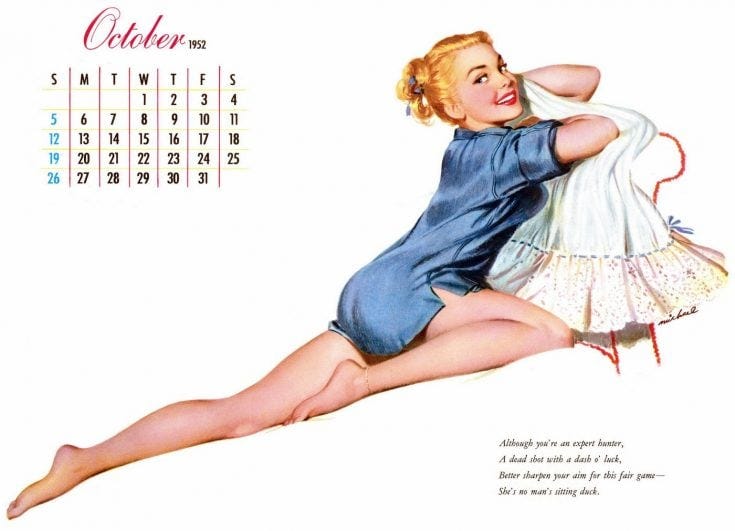

Pop was a mechanic. He ran the garage for the fleet of delivery trucks for Northern New Jersey Oil Company, in Newark. Sometimes, on Saturdays, I would go with him to the garage. The there was a kind of caged area there were the tools and workbenches were; Pop kept the master key. And on the walls above the workbenches there were calendars, helpfully provided by tool manufacturers. And there were pictures on those calendars.

Starting when I was around 9 or 10 those pictures began to do something to me. Something I didn’t understand but felt to be vaguely sinful (though I of course would never mention it during confession). It was a thrill from my toenails to my scalp, and I couldn’t imagine how Pop and the other men who worked there could stand it. If I had had to stand in that cage for eight hours a day with those marvelous, mysterious, absolutely wondrous creatures staring down at me I would have vibrated until I disintegrated.

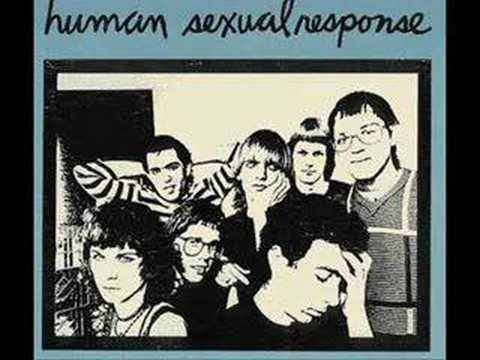

Human Sexual Response

Human Sexual Response — A report on clinical findings about human sexual response patterns and orgasmic expression is of course the title of the landmark book by Masters and Johnson.

More importantly, Human Sexual Response is the name of the best post-punk rock band to ever come out of Boston: a loud virtuosic Cream-like trio of guitar, bass and drums fronted by four singers — three men and one woman.

During their heyday in the early 1980’s, their hard-driving power-pop songs filled the local airwaves, and their shows were legendary.

Their best nationally known song is probably Jackie Onassis, but my personal favorites are the wryly metaphysical “Andy Fell” and the song that first put them on the Boston map, “What Does Sex Mean to Me?”:

Late at night I walk through town I eye every one I meet I want to follow them all home But I just follow my feet Into the book store I see lined up Virgins Die Horny Sitting next to The Hite Report Sitting next to Love Story And I ask, What does sex mean to me? And what does sex mean to society?

The singer of ‘Jackie Onassis’ was of course Casey, who I hired to be a technical writer at Sun Microsystems. We worked together for six years. She was a rock star of many talents.

Xavier

So off I went to Xavier High School, in New York City, commuting in my military uniform up to an hour and half each direction, while my home town of North Caldwell continued to rapidly suburbanize, with the last few farms there like the one I had grown up on carved up into half-acre plots where new houses, like the one Tony Soprano would later live in, sprouted up.

I got used to riding the subways of New York (and mastered the art of sneaking into them to avoid the 20-cent fare; 20 cents was the price of a Sabrett hot dog), and I studied hard — four years of Latin on top of a pretty intense curriculum — and I learned how to do close-order drill (“column left, flank right, double-about to the rear, march!” )by practicing at the 26th street armory for more than an hour after school every Tuesday, and I got drunk in Union Square Park before going to shows by Jethro Tull and Grand Funk at Filmore East. By graduation day, 1970, I was a farm boy no more; I was a city kid and barely even a resident of the town I lived in. I hardly ever saw Ande. Maybe a few times a year. If that.

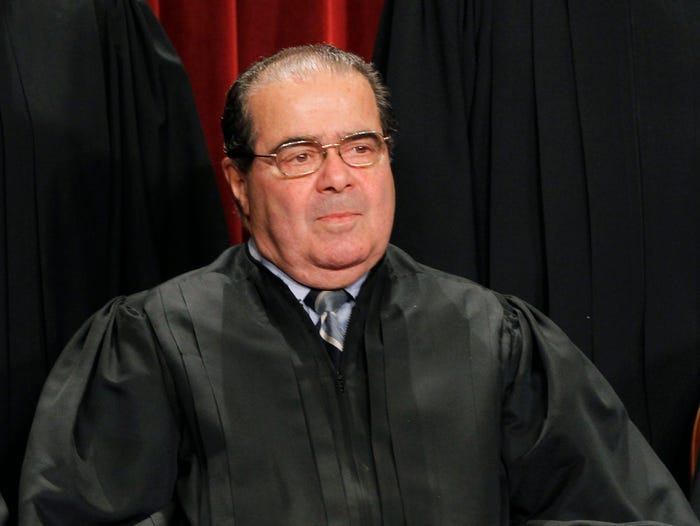

At Xavier, some students got really into Catholicism, and some of them got really into the military stuff — strutting around with shiny shoes and polished brass and rising up in rank in the Xavier Regiment — and some, like the famous Son of Xavier Antonin Scalia, got into both of them. Generally speaking I avoided kids like that.

If you’re curious about what it was like back then when ROTC was compulsory, my classmate Peter Reilly has gathered a bunch of essays about it, many written by him.

Thanks to the circumstances of my high school and to my natural reticence, especially around girls, my dating experiences were few and awkward, and certainly had nothing to do with sex of the non-imaginary kind.

By the time I left 16th street for good, Xavier had taught me two important things about myself: the military was not for me, and neither was Catholicism. And sex? Sex was something to wonder about, that’s all.

I put my finger to my tongue I taste vagina I licked Betty Ford's boots (it's true) She wore 'em all over China People say that Chinese people don't Ball as much as we do 'Cause their cultural revolution has shown There are more important Things to see to So I ask, What does sex mean to me And what does sex mean to society?

Altar boy, Jesus girl

I have no recollection of how or why I became an altar boy. At that time I was also a Boy Scout. Maybe I thought being an altar boy would help me get a merit badge. Who knows. I started at age 10, 5th grade, and I think I quit when I was in 7th grade. I was an altar server at masses in the priest’s residence, in the West Essex High School auditorium, and in the brand new Notre Dame Church, when it opened for business in 1965.

By the time I was in high school I was already starting to think the whole business was kind of silly.

My wife Betty grew up amid Southern Baptists in Evansville, Indiana. One of her grandfathers was a hellfire and brimstone Baptist preacher, as were two of her uncles. This is how she recounts the story of her being ‘born again’: “I was about nine years old. I remember the hat I was wearing; it was black with lace trim and had fake pearls all around the back. The preacher was telling a story about a little girl who had died and had gone to meet Jesus. It was very sad and I started crying. People around me heard me crying and started making a fuss that I was getting reborn with Jesus in my heart. So they pushed me up to the front of the church and everybody cheered while I cried. Then when we went home I got ice cream.”

By the time Betty finished high school, she too had had enough of religion.

I see another baby born One more mouth to feed Sometimes I can't comprehend This urge to breed Travel through a crowded land Where people love each other as they love the state They love their work Their work is love Love's no excuse to procreate Their party slogan reads And I quote Making love is a mental disease It wastes time and Depletes our energies

Hazel Motes lives on

Hazel Motes, the protagonist of Flannery O’Connor’s novella Wise Blood, is a street corner preacher of “The First Church Without God — where the blind don’t see, the lame don’t walk, and what’s dead stays that way”. Despite his rejection of God and his loathing of religion of any sort, Hazel can’t seem to get away from them. Close readers of my novels may have noticed that I have a bit of Hazel Motes in me.

In the next issue of Sundman figures it out!, entitled Dead Car in the Driveway, I’ll be talking about how despite my having left religious belief behind by the time I was 16 or so, Catholic and Christian themes and theological concerns run through my books, especially Acts of the Apostles, Cheap Complex Devices and The Pains. In that post I’ll venture some thoughts about how the religious experiences had by me and by Betty as children can perhaps illuminate how cults come to be, and what they can tell us about our current situation.

Now I wonder what you think about When you're lying there in bed Someday I think I'll find you out Push my finger through your forehead It's just a kind of acupuncture Wisdom from the east When my finger presses your third eye Your secret life is released

And of course I’ll talk about Catholicism’s weird sexual hangups, which I somehow haven’t managed to get to yet.

Pretty please click this promo link

I’m participating in another book giveaway. Sign up for an author’s mailing list, get a free ebook. This promo’s for thrillers, and I’m giving away Biodigital to anyone who signs up. If you’re on my list already and would like a copy of Biodigital, just enter with whatever email address you use for substack. Every link-click helps me, even if you don’t sign up for any lists. This ends May 10, and I promised the organizers that I would send out an announcement last week. Yikes! Please click!

On facebook, a friend wrote (under my post about this essay), "A born and undisturbed atheist, I muse with I hope compasionate sadness at my Catholic friends who seem able to reject it, but not to forget it."

My reply:

"Is 'compassionate sadness' a fancy-pants way of saying "pity"? Hrrmmm. . .

I don't consider myself traumatized by Catholicism (although others, who had much worse experiences than I did, certainly were.) I was brought up in a loving home in truly bucolic, one might even say idyllic surroundings. And although I didn't enjoy it at the time, I rather often hated it, in retrospect my country-boy/city kid experience gave me from a young age a much broader understanding of the varieties of human experience than many people seem to get in a lifetime.

I don't pity kids who didn't grow up on a small farm & learn to milk a cow when they were 5 years old or get comfortable exploring Brooklyn & Queens & The Bronx and Manhattan by subway starting at 13. I just feel lucky that I did. It was certainly a richer experience than many kid stuck in suburbia ever got or get.

As for the Catholicism, it was just kind of there, like the Scottish or Irish accents of every one of my adult relatives except for Pop."