Toxoplasmosis, my Pazuzu, part aleph-null

An AI conundrum, a Ted Chiang parable, and the dubious gift of an ancient Mesopotamian demon

Sundman figures it out! is an autobiographical meditation, in the spirit of Michel de Montaigne, of a 71 72 year old guy who lives with his wife in a falling-down house on a dirt road on Martha’s Vineyard that dead-ends into a nature preserve.

Incidents, preoccupations, themes and hobbyhorses appear, fade, reappear and ramify at irregular intervals. If you like this essay I suggest checking out a few from the archives. These things are all interconnected.

Précis

As long-time readers of Sundman figures it out! know, my 42 year old, variously handicapped son Jakob has lots of challenges due to his having been infected, before he was born, by the toxoplasma parasite. I have likened his condition of congenital toxoplasmosis to the ancient Mesopotamian demon Pazuzu, of the movie The Exorcist (and its many sequels), and myself to Fr. Lankester Merrin.

Recently Mark Gibbs, a longtime fan and sometime critic of Sundman figures it out!, started his own substack, called The F*ck You Muscle. In an essay of a few weeks ago, Beauty is in the AI of the Beholder, Gibbs wrote about an AI-generated model of idealized feminine beauty created by a team of marketers to promote a line of women’s clothing. What can we learn from this episode, Gibbs asked, about how we perceive beauty, about how consumerist capitalism works, about how AI warps perceptions and disempowers people? Gibbs’s essay got me thinking about Ted Chiang’s 2002 novelette Liking What You See, which explored similar territory.

So I re-read Liking What You See, and that in turn got me thinking about how my son Jake, whose brain and retinas were feasted upon by the toxo parasite before he was born, perceives or does not perceive beauty.

A come-along

In March of this year I wrote an essay about how, en route from Massachusetts to New Jersey to attend the funeral of a beloved uncle1, I became too ill to drive and pulled off the highway to find someplace to rest and spent the next two days in a fever dream: New Haven Motel 6 Vortex Sutra: a bauhaus sickroom fever meditation on the evil of our days.

The funeral I missed was Uncle Harry’s. I recently had occasion to use the big yellow crowbar seen in the photo below. This thing always makes me think of Harry. He called this kind of tool a ‘come-along.’ As in, ‘you come along with me.’

The relevance of this tool to the topic at hand will become apparent eventually.

Backgrounder

A little over 42 years ago my son Jakob was born, six weeks prematurely, sickly and frail. His first year was rough; he really didn’t seem to want to be here. But my wife, Betty, Jakob’s mother, is a stubborn soul and she kept him alive. Eventually we learned that Jakob had been infected in utero by the toxoplasmosis parasite. I’ve written several Sundman figures it out! essays on the consequences, the so-called adverse sequelae, of that little sky-anvil2. Toxoplasmosis, my Pazuzu. Part one is probably the place to start if you’d like to get caught up.

Aleph null (ℵ₀) is the smallest infinite cardinal number, representing the size of the set of natural numbers. It indicates that there are countably infinite elements in a set that can be matched one-to-one with the natural numbers.

Sometimes I feel like I have had an infinite number of encounters with this demon.

Meta-face

Here’s the imaginary human that Mark Gibbs writes about in his essay Beauty in in the AI of the beholder:

Gibbs writes:

There’s a name for the new look. Vogue Business called it “the meta-face.” Perfect symmetry. Skin like vinyl. A machine’s dream of a person. And it’s everywhere. Digital influencers who aren’t alive. Brand mascots who never age. It’s cheaper. It’s controllable. It doesn’t ever say, “That’s enough, I need a break.”

People pretend this is about innovation. No. It’s about obedience. An AI face doesn’t complain about the heater blasting during a twelve-hour shoot. It doesn’t fight for a raise. It doesn’t have a bad day, or call out racism, or say the words “union dues.”

A tar pit of the mind

I twist myself into knots writing these Pazuzu essays because in trying to figure out what I want to say I can’t help feeling that I’m trading on my son’s disabilities, which feels obscene; or worse, that I’m presenting him as a nothing but a collection of those disabilities. But Jake encourages me to share his story, so people will learn what life is like for people with disabilities like his.

I waste so much time fretting. I shall try to just write. I wish it were easier.

Jakob describes himself as being ‘on the spectrum,’ but he’s never been diagnosed as having autism. The most challenging job he’s ever had, at which he was very good, to which he commuted two hours each direction — three bus segments and a 45-minute ferry ride — was as a greeter for the Wal-Mart in Falmouth. But one day in 2017 he woke up paralyzed, and, 8 months later, after he had regained 90% of his prior mobility, Wal-Mart told him that he wouldn’t be getting his job back.

There is no easy way to describe his intellectual ability. One way to look at it is that he lasted two whole semesters at Bridgewater State College before flunking out, and he can talk to you about Freudian and Jungian psychology or theories of how humans populated the Americas; another way is that he hasn’t yet learned that onions, bananas and potatoes don’t go in the fridge. Too much exposure to everyday reality — especially social reality — can trigger a massive seizure.

When he was five years old, already far behind on all kinds of developmental milestones, he amazed my brother Mike by recounting some obscure fact that you wouldn’t expect a developmentally-delayed five year old to know.

“Jakob,” my brother said. “How did you know that?”

“Uncle Michael,” Jakob solemnly intoned. “My brain is like the La Brea Tar Pit. Things go in there and they don’t come out.”

Ted Chiang’s ‘calliagnosia’

From Wikipedia:

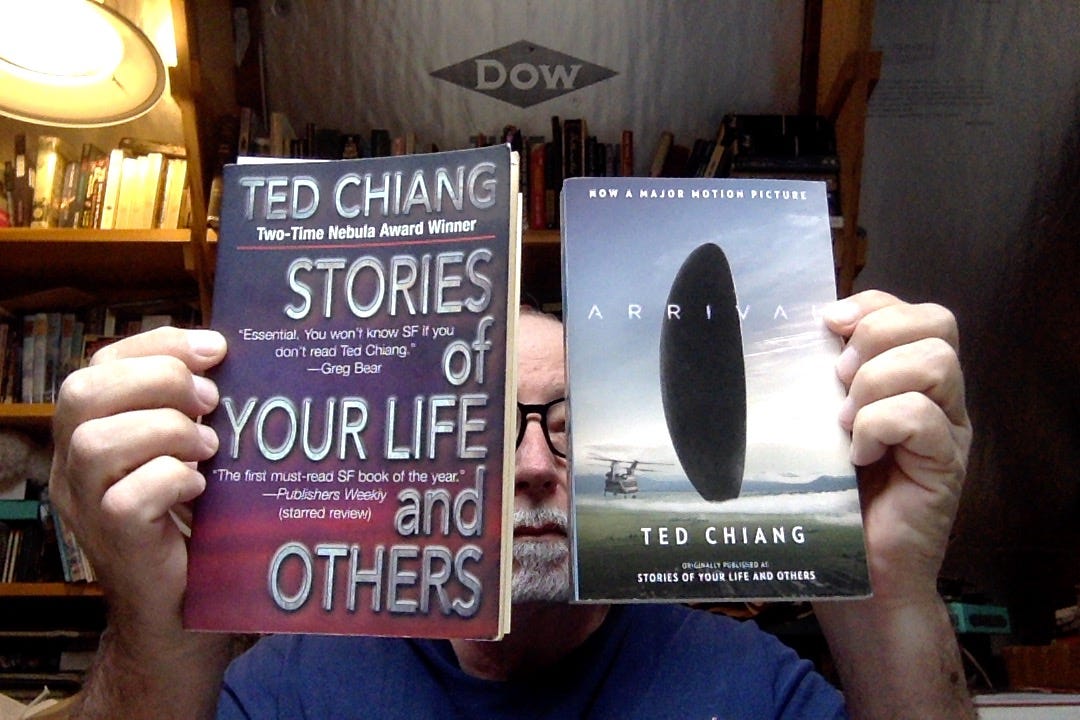

Liking What You See: A Documentary is a science fiction novelette by American writer Ted Chiang, published in the 2002 collection Stories of Your Life and Others.

The novelette examines the cultural effects of a noninvasive medical procedure that induces a visual agnosia toward physical beauty. The story is told as a series of interviews about a reversible procedure to induce a condition called calliagnosia, which eliminates a person's ability to perceive physical beauty. The story's central character is Tamera Lyons, a first-year student who grew up with calliagnosia but wants to experience life without it.

As one of the characters in the story describes it,

[Calliagnosia] is called an associative agnosia, rather than an apperceptive one. That means that it doesn’t interfere with one’s visual perception, only with the ability to recognize what one sees. A calliagnostic perceives faces perfectly well; he or she can tell the difference between a pointed chin and a receding one, a straight nose and a crooked one, clear skin and blemished skin. He or she simply doesn’t experience any aesthetic reaction to those differences.

In a note explaining how he came up with the story, Chiang wrote:

Psychologists once conducted an experiment where they repeatedly left a fake college application in an airport, supposedly forgotten by a traveler. The answers on the application were always the same, but sometimes they changed the photo of the fictitious applicant. It turned out people were more likely to mail in the application if the applicant was attractive. This is perhaps not surprising, but it illustrates just how thoroughly we’re influenced by appearances; we favor attractive people even in a situation where we’ll never meet them.

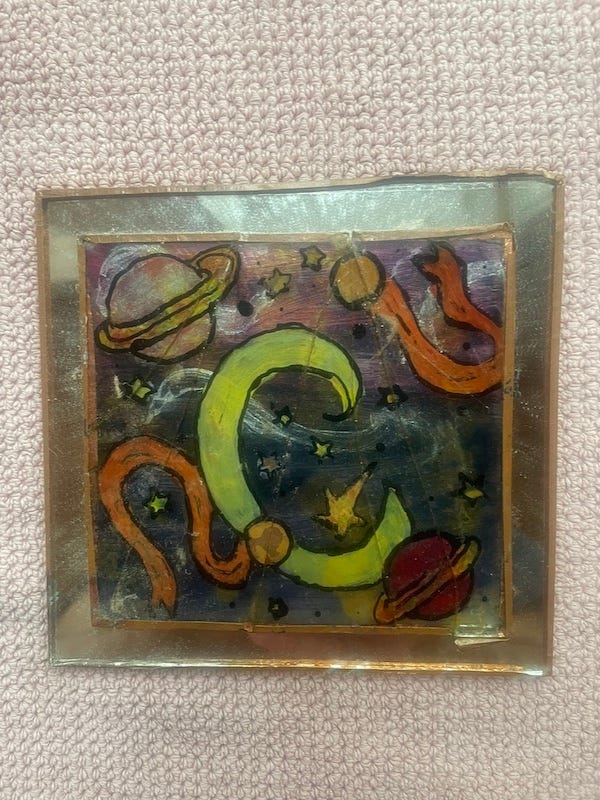

Planetary time capsule

More than twenty years ago, shortly after Betty and I purchased our falling-down house, I somehow let one of Jakob’s painted-on-glass paintings slide into a crevice between a bathroom cabinet and a wall. There the painting stayed, forgotten by all but me, until last week, when I decided to use that yellow come-along to move the cabinet six inches to the right and retrieve it. I felt compelled to see how well I remembered it.

It’s a picture painted on a small glass square that’s affixed to a mirror. The painting cracked into several pieces, but the mirror didn’t.

Before we moved into our falling down house we lived in another house with a wooded back yard. One year, when Jakob was about 13, still a student in public school, where he was sometimes bullied but more often just ignored, he, and his two sisters, and his mother and I each made jack-o-lanterns, which we put on the second floor balcony. A week into November it was time to get rid of them, which we did by throwing them off the balcony into the woods.

I threw mine first, saying, “Goodbye, cruel world.” Betty then tossed hers, saying “I just don’t want to be here any more.” Jakob’s two sisters went next, with similar final words. Jakob went last. “I feel so empty!” he said, as he awkwardly tossed his pumpkin to its demise.

A Jake update

I write this essay in the context of Jakob once again being in the Royal Falmouth Nursing Center where he’s been getting physical and occupational therapy to deal with another bout of spinal stenosis (which will probably require a third operation, but not quite yet), and his worsening vision — which was very poor to start with.

Jakob began this summer with a week-long stint at Martha’s Vineyard Hospital over Memorial Day weekend after some seizures and falls, and found himself back there on the fourth of July for similar reasons, including loss of ability to control his hands. He was transferred from Martha’s Vineyard Hospital to Falmouth, where he’s been since then. During this time I’ve taken Jakob to a consultation with his neurologist in Boston and his neurosurgeon in Jamaica Plain. We also had one 24 hour visit to the E.R. at Brigham & Women’s Hospital, where MRIs, CT scans, X-rays & other diagnostic procedures performed.

For forty-two years Jake and I have shared adventures in the backs of ambulances, in doctors’ offices, in emergency rooms and rehabilitation centers.3

This summer it’s been more, and more, and more of the same. There’s no end to it. Aleph-null. Countable infinity.

When will I find the time to think, to write, to work, to make money to pay my bills?

On Tuesday I was with Jakob at Royal Falmouth when a nice fellow from the Massachusetts Commission for the Blind was there to teach him how to use his new iPad with voice controls, since he can barely see and his hands barely work anymore.

Today he told me that he can’t turn on voice activation on his iPad because to do that you have to double-tap an icon on the screen, and he can’t move his fingers that fast. I’m sure there’s a workaround, but that’s one more thing for me to put on my worry-list.

And then he told me that he needs clothes. He has nothing to wear but a hospital ‘johnny.’ But last week he had two changes of clothes! It’s a long story. You don’t want to hear it.

So I think I’ll head over to see him tomorrow, bringing some clothes; see if I can get the iPad working for him. Park the car near the Vineyard Haven library, walk a quarter-mile to the boat, go into the ferry terminal & buy a ‘geriatric, round-trip’ ticket, ride the ferry 45 minutes to Woods Hole, take the Steamship Authority bus 15 minutes to the Palmer Avenue parking lot, walk a mile and a half to Royal Falmouth Nursing Facility. Spend an hour or two there and make the return trip, sans laundry. Not how I had planned to spend my Saturday.

At least the forecast calls for reasonable weather. When I made the trek three days ago it was 90 degrees in the shade. Felt like I was back in the Sahel.

Aleph-null.

Pazuzu, alas, is back.

Face blindness

Due to brain damage caused by congenital toxoplasmosis, Jakob has face blindness. He recognizes people — including me, his mother and his sisters — by their voices, not by their physical appearance.

From Wikipedia, (edited by me):

Prosopagnosia, also known as face blindness, is a cognitive disorder of face perception in which the ability to recognize familiar faces, including one's own face (self-recognition), is impaired, while other aspects of visual processing (e.g., object discrimination) remain intact.

The brain area usually associated with prosopagnosia is the fusiform gyrus, which activates specifically in response to faces. The functionality of the fusiform gyrus allows most people to recognize faces in more detail than they do similarly complex inanimate objects. For those with prosopagnosia, the method for recognizing faces depends on the less sensitive object-recognition system. Under normal conditions, prosopagnosic patients are able to recognize facial expressions and emotions.

Acquired prosopagnosia results from occipito-temporal lobe damage and is most often found in adults. It is subdivided into apperceptive and associative prosopagnosia. In congenital prosopagnosia, the individual never adequately develops the ability to recognize faces.

Prom Night at Perkins

In 2003, on the joint occasion of the 50th anniversary of Watson & Crick’s elucidation of the structure of DNA and the completion of the Human Genome project, I wrote a long essay for Salon called How I decoded the human genome.

How I decoded the human genome, revisited

This post is mostly about a long (2-part) essay I wrote for Salon in 2003, called How I decoded the human genome, which was about implications of humankind’s ever-increasing understanding of the workings of DNA and our ever-increasing mastery of genetic engineering. But by way of introduction I would like to offer a few observations on this

Here’s the section of that essay called “Prom Night at Perkins.”

Prom night at the Perkins School for the Blind, in Watertown, Mass., is in many respects just like prom night anywhere else. Kids get dressed up, they listen to loud music, they dance. They think about graduation and they dream and worry about the future.

But in other respects, prom night at Perkins is unlike prom nights at most other high schools across the land. For one thing, most of the students are blind. Those who are sighted have poor vision. But virtually no Perkins students have blindness as their only handicap. Helen Keller, the school’s most famous alumna, was deaf and blind and had lost years of prime learning time before the miraculous intervention of Anne Sullivan, her nearly blind Perkins teacher. Helen Keller would fit in perfectly at Perkins today. To these kids, mere blindness is almost trivial.

It’s hard to pigeonhole Perkins students. Some of the students use wheelchairs or walkers, but others are athletes. Some have autism, many have intellectual impairments, but some score 800 on their college boards. Some look like Tom Cruise or Nicole Kidman, others have facial deformities. Some are gifted musicians; others are deaf. And once in a while there is a gifted deaf musician. Some of the seniors, upon graduation, will be going off to college; others will take up residence in a group home or move back in with their parents. Some listen to Eminem, others to Randy Travis, and some have tastes that are totally inscrutable.

But the one thing all Perkins students have in common is that they have lived the trauma of being different. They are mutants and they know it. And some, the more sophisticated among them, know that had prenatal genetics tests for their conditions existed 15 or 20 years ago, they wouldn’t even be here.

On prom night last spring I spoke with several Perkins students about this whole topic. I particularly remember one student named Jakob. He’s a 20-year-old junior who has several profound disabilities and who has been in and out of hospitals much of his life. Like Helen Keller and like many of his own friends, he has had several brushes with death — most of them in his first 10 years. He has had eye surgery, experimental drugs that nearly killed him, and emergency brain surgery at 6 o’clock one morning to keep his head from exploding. He has the kinds of conditions that lead people to choose abortion rather than carry to term damaged fetuses — sometimes after using a “quality of life” calculus that is beyond my comprehension.

He’s a smart but socially awkward guy, traumatized by 10 years of isolation and ostracism in mainstream schools but now perfectly at ease at Perkins, who reads fantasy books by the truckload — holding them 2 inches from his face until his eyes fatigue and turn inward.

I asked Jakob how he felt about the idea that, thanks to the Human Genome Project, in the future, kids like him and his friends need never be born. (Although Jakob’s disabilities were caused by prenatal infection and not by a genetic abnormality, that’s academic. He well knows that he’s just as much a mutant as any of his friends.) He thought for a few seconds, and then said in a voice dripping with irony, “Hello, justifiable holocaust.”

A gift of ignorance from the unholy demon Pazuzu?

Another snippet from Ted Chiang’s Liking What You See

The deeper social problem is lookism. For decades people’ve been willing to talk about racism and sexism, but we’re still reluctant to talk about lookism. Yet this prejudice against unattractive people is incredibly pervasive.

For most normally-sighted people with intact fusiform gyruses, people like me, and perhaps you, I expect that the idea of Chiang’s ‘calliagnosia’ — the ability to perceive or not perceive physical beauty in human faces and bodies that can be turned on or off as easily as you can change your hair color — is intriguing.

But I also expect that to most people who are blind the question is moot.

According to the wikipedia entry on prosopagnosia, people who have that condition are still able to recognize ‘facial expressions and emotions’. Which leads me to wonder, can they distinguish between a face that most people would consider ‘beautiful’ and one they would consider ‘plain’? That is to say, does prosopagnosia imply calliagnosia?

In Ted Chiang’s novelette, some characters who have had calliagnosia from infancy come to regard it not as an impairment, but as a gift. Because they’re not distracted by whether someone is ‘hot’ or not, or even if they’re hideously ugly, they can focus on more important things. But of course if all the characters felt that way it would make for a pretty boring story, and no story by Ted Chiang is ever boring. You should read his stories and see for yourself.

Jakob, like many people who have autism, has difficulty, often, in discerning emotions in other people. So far as I can tell, this difficulty does not benefit him in any way.

But he also apparently has some variant of calliagnosia. He literally does not notice whether someone is good looking or not — nor does he pay much attention to any disabilities or impairments. I admire this about him.

I even think, sometimes, that maybe this — his immunity to lookism — is the one gift that that fucking demon Pazuzu has given him.

Let’s not ignore the elephant

I hate to be a downer, but it would be immoral of me to write about Jakob’s challenges while skirting the dreadful American Nazi reality that now surrounds us USians. So I close with these ‘words to think on’ from a recent post by by Dean Obeidallah: Trump and the GOP’s goal is to “exterminate” the disability community.

“They want to exterminate us.”

Those were the blunt words of Steve Way—a long time disability rights activist—to describe Donald Trump and the GOP’s multi-front war targeting the disability community. Way—who was born with Muscular Dystrophy—explained that the GOP’s cutting $1 trillion dollars from Medicaid, gutting of the Department of Education and rolling back of protections for the disability community are all intended to make them “undesirable.” He added in a very matter of fact way, “They want to get rid of us,” that is why, “we need to call this for what it is: It's eugenics.”

Aktion T4

Nazi Germany's programme of euthanasia which claimed 275,000–300,000 victims

Aktion T4 was a campaign of mass murder by involuntary euthanasia which targeted people with disabilities and the mentally ill in Nazi Germany. The term was first used in post-war trials against doctors who had been involved in the killings. The name T4 is an abbreviation of Tiergartenstraße 4, a street address of the Chancellery department set up in early 1940, in the Berlin borough of Tiergarten, which recruited and paid personnel associated with Aktion T4.

If you don’t think the fascists in charge of this country won’t create our own American Aktion T4 program if given half chance, or that they wouldn’t delight in putting people like my son Jakob in it, may I kindly ask you to find the courage to face reality.

And I swear by all things holy if I told you what I wish I could do with that yellow metal come-along. . .

Please, go read Obeidallah’s article.

Passing the collection plate

I’m just a poor writer who’s trying, and not always succeeding, to make enough dough to pay his mortgage & car payments on time. (My situation is actually pretty scary right now, and Pazuzu ain’t helping any.) If you enjoy my kind of writing and would like to help out, please consider upgrading to a paid subscription. If you’d just like to make a one time-contribution, here’s a link to buy me a coffee (any amount welcome — pay no attention to the exorbitant suggestions).

I’m now offering ‘merch’ at my ‘Buy me a coffee’ page. The first item on offer: In Formation #3.

Cheerio!

P.S. If you would like to send a card to Jake, please address to

Jakob Burton-Sundman C/O John Sundman P.O. Box 2641 Vineyard Haven, MA 02568

I’ll make sure he gets it.

Harry Seebode: https://www.legacy.com/us/obituaries/name/henry-seebode-obituary?id=57537406

You’re walking down a pleasant street on the edge of a park were people are smiling and children are laughing and playing on a beautiful summer day, not a care in the world. Out of a cloudless sky an anvil falls on your head.

Betty of course has been and is a full partner, but it has just worked out that I am Jakob’s medical proxy and the person who mostly deals with this stuff. Besides, we have plenty of other ongoing crises in our family for her to deal with.

Wow. Great post ... great as in droll, disturbing, and poignant all at once. I remembering reading your piece from Salon ages ago but rereading it (https://www.salon.com/2003/10/21/genome_5/) in the light of what the Trump administration is doing brings home the horrific, inhumane reality of their plans. And Obeidallah's article is a must read. If you can finish it without feeling sad, angry, and disgusted simultaneously, you must have a heart of stone. You and Obeidallah illustrate that for the Trumpists, there's nothing they're not willing to do to institute their new order.

Great article, I really like how you concatenate apparently unrelated things just to deliver such insight about the precarious situation in which we find ourselves.

In something unrelated, how does it work to buy the magazine from the Buy me a Coffee website?

They want to charge me without knowing where to send the magazine, you suggest to buy direct from the publisher if one is out of the USA but they don't deliver to sunny Spain for some reason.