How I decoded the human genome, revisited

Reconsidering my short career in bioethical punditry

This post is mostly about a long (2-part) essay I wrote for Salon in 2003, called How I decoded the human genome, which was about implications of humankind’s ever-increasing understanding of the workings of DNA and our ever-increasing mastery of genetic engineering. But by way of introduction I would like to offer a few observations on this Sundman figures it out! project.

Every time I mail out a new issue in this series a few people unsubscribe. Substack offers me the option of receiving a notice whenever someone opts out, but I don’t use it. I’ve never checked the list of unsubscribers. I guess I feel it’s none of my business. (Or maybe I just don’t want to get my feelings hurt when an old friend leaves.)

What I do keep track of is how many views each post gets, and how many times posts get shared, and especially how many new subscriptions each post generates.

My second-ever post, Dark side of the hut 50 years later, about a remarkable experience I had in tiny, remote, impoverished African village during a time of famine, pestilence and drought, is the all time leader in views (approaching 4,000) and subscriptions generated (87).

Next highest is Albert, unforgotten, a remembrance of my childhood best friend, who was murdered in a liquor store holdup in the 1980’s. That has been viewed nearly 2,000 times.

Rounding out the top three is Crawling under Carly Simon’s house, a story from my construction-worker days. That comes in at around 1.5k views. Most of my other stories get between 1k and 1.5k views.

Stories about what one might call ‘technopotheostic’ themes — themes which, not incidentally, pervade my novels: biodigital convergence, the elevation of technology to god-like status, the ‘singularity’ AKA ‘overmind’ — do OK, but not great.1

As I’ve mentioned here before, my friend Mark keeps telling me to stop writing about anything that doesn’t have to do with biodigital technopotheosis. “Your purpose is to generate interest in your novels, John. Not interest in astral sex with hot travel agents.” He tells me that I should exclusively write about the bewildering and ever-evolving technosphere that we inhabit.

What I'm doing here in Sundman figures it out! is thinking out loud, learning by doing, hoping that you find my preoccupations worthy of a few minutes of your attention every now & then. I know it's not for everybody. If you decide to unsubscribe I wish you well, but I would love to hear from you on the way out the door. And of course if you stick around I'd love to hear from you as well.

Set Your Wayback Machine to October, 2003

I became acquainted with Andrew Leonard, who was then the editor of Salon’s ‘technology’ section, when he wrote to request a copy of my novel Acts of the Apostles after reading this review in Slashdot. Leonard’s review of Acts, “Hacking the Overmind” was the first to introduce my book to a general audience. After that he commissioned me to write a few essays, including one on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of Watson & Crick’s elucidation of the structure of DNA.

In the course of researching that article I travelled from San Diego to Boston and points elsewhere, talking with scientists, philosophers, bio-luddites, disability rights advocates and regular people as well. I sure put a lot of work into it for the fifty bucks or whatever it was that Salon paid me.

The first part of the essay bore the title I gave it, How I Decoded the Human Genome. The second part had a title that my editor gave it, One Vote for the New Eugenics. This title, alas, was based on an unfortunate misunderstanding of a comment made by my wife Betty, which I'll discuss a bit later.

In re-reading this essay for the first time in more than a decade I was generally happy with how well it has held up. Sure there are some things that make me wince a little, and one or two trivial facts I got wrong. Also, it contains personal information about some people that was included with their permission, then, but which I wish I could update now. But in general I think it's pretty damn good.

Rereading this essay also made me feel fine about not covering in Sundman figures it out! the foundations of my moral/philosophical inquiries into the bewildering and ever-evolving technosphere that we inhabit, since such things are covered in the Salon piece. So I hope you'll read it if you want to know more about how I got here.

“Rosalind Franklin’s crystallography reveals God’s schematics for James Watson and Francis Crick to decode”

Here's a few paragraphs from the near the start of part one of How I decoded, which opens with me attending a lecture at a scientific conference :

I sat in the back row, near an exit, and tried not to have a panic attack. My career as a moral philosopher was only 6 hours old but already I could smell it going up in smoke.

I had come to San Diego looking for a deep understanding of the meaning of life, which I was planning to bottle and sell at a decent markup. I wanted to address the questions that have been implicit ever since Rosalind Franklin's crystallography revealed God's schematics for James Watson and Francis Crick to decode: What is a human being? What is our worth? Who decides?

But all I was getting was science, and that was bad. Now, science is OK, of course, for people who like that kind of thing. But I had come to the O'Reilly conference on a self-financed gambit to elbow my way into the moral-philosophy racket. I figured that if Bill Bennett and similar gasbags could make millions spouting mere platitudes and recycled 15th century theology, then I should be able to make a few large, at any rate, for genuine insight into ethical quandaries occasioned by 21st century breakthroughs in biological science.

Especially in 2003, the golden jubilee of Watson and Crick's seminal eureka. It was the proverbial Klondike opportunity, but in order to cash in I would need to come up with some salable wisdom that was predicated on an actual understanding of current DNA technology. So that's why I was sitting in Dr. Cooper's lecture and waiting for profound insight.

“One vote for the new eugenics” — and what Betty really said

Andrew Leonard, my editor at Salon (and who I very much enjoyed working with), gave part two of my essay the title “One vote for the new eugenics”. That was unfortunate. He had taken something my wife Betty had said and twisted to mean something she had not intended.

Now Betty, as some readers may recall from my Shifted reading frames essay (or from this mention of The Great Figure) holds an advanced degree in molecular genetics. Her dissertation was on shifted reading frames and overlapping gene products in single-stranded DNA bacteriophage, and when she presented her results to a standing room only audience at the legendary phage symposium at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory in 1978 both Watson and Crick were in attendance, standing at the back of the hall. All of which is to say, Betty has some familiarity with DNA and its manipulation.

So as you'll see if you read that Salon essay, what Betty said, on the subject of genetic engineering, was 'one cheer for the new eugenics.’ Not one vote. One cheer. One cheer being, that is, less than three cheers, less than two cheers, but nevertheless more than zero cheers. By which she meant that she could see the potential for genetic editing to eliminate inherited diseases and things like that, but she was very wary of the whole eugenic prospect.

I thought is was a great quip. I don't know how my editor, otherwise a very astute fellow, missed its meaning.

DNA, capitalism, consumerism, and hot astral sex

Anyway here's a few more paragraphs from my essay, near the conclusion of One vote, part two of the How I decoded essay:

Let's stipulate that as an inevitable consequence of the deoxyribonucleic decryption by that dihelical duo Watson and Crick, humanity's eclipse has begun in earnest — incidentally catching our medieval theologies (and even Bill Bennett?) — a tad off guard. In other words, because the DNA cat is out of the bag, we humans are doomed to be superseded by whatever we engender. For whatever reason, this is a prospect unsettling to many of us, and That Old Time Religion offers scant consolation to anybody who might care about the demise of Homo sapiens and who also has at least half a brain.

Let's further stipulate that, just as once-criminal pornography — now disguised as consumer advertising — is force-fed to children in public schools under corporate mandate, Hitlerian notions of what is and isn't human are, in 2003, fundamental, commonplace American consumerist dogma. In our culture, now more than ever, the beautiful are gods. And the disfigured, paralyzed, blind, deaf and mentally ill are at best an unavoidable nuisance, at worst an intolerable, "politically correct" burden on the rest of us decent folk. If you don't believe me, ask Rush Limbaugh. Or MTV.

Let's stipulate that here in Karl Rove's America, our moral universe is predicated on our economy, that our economy is predicated on consumerism, that consumerism is predicated on narcissism, and that the narcissist, the driver of our economy, is driven by the search for his or her own physical perfection and the derivative perfection of his or her own children, pets and other possessions.

Obviously this perfection obsession at the root of our culture is thoroughly enmeshed with sex, the DNA-driven urge each of us feels to find the perfect vector to propagate our own deoxyribonucleic heritage. We are biologically programmed to procreate, and, at that, to procreate with the best available evolutionary stock. In a capitalist system, that optimal evolutionary stock follows the money. In our world good looks and physical exceptionalism are supremely marketable commodities, as Michael Jordan can explain much better than I. Therefore America (along with its copycats) stands for nothing if not the moral imperative of its wealthiest, best-looking people to do a lot of fucking. I'm sure we can all agree on that.

What It Means to Be On Our Own

In reflecting on the experience of researching that essay more than twenty years ago, pondering the subject deeply, struggling to put my thoughts into words, what struck me was not so much my own perplexities, but the meta-issue of how, just like me, many, perhaps most thinking people — including you? — are trying to decode the human genome; trying to figure out what the Human Genome Project calls "ELSI"— the ethical, legal, social implications of all this stuff, trying to figure out what this particular aspect of technopotheosis means to us as individuals, societies, and as a species.

As I was googling for my own essay, I came upon this Youtube video about decoding the human genome. Its presenters claim to have figured out the meaning of that enterprise, and it has to do with what they call "the God gene."

This video presents mishmash of pseudo-scientific gobbledy-gook which, depending on your point of view is funny, depressing, scary, or maybe something else. I myself found it both depressing and scary, which is why I only watched a few minutes of it. But it points up the larger issue of how people make up their own reality when 'real' reality is inaccessible to them for whatever reason.

Built into this process is the notion, which perhaps in Western culture goes back to the Reformation, that we don't need 'experts' to explain complicated things to us — we can figure them out ourselves. We don't need priests to explain the Bible to us, or professors or scientists to explain vaccines or changes in the global climate. We'll be our own instructors.

Especially in the age of the Internet, this notion can be both seductive and positively intoxicating. Depending on where you go from this premise, you can wind up in a democratic place of curiosity, self-empowerment and serious inquiry, or you can end up down a rabbit hole of antivaxx, QAnon or some other occult land of make-believe.

But how do we know if we're in the land of serious inquiry or down the rabbit hole of magical thinking? And when you add in recent developments in AI, with all of its colossal potential for creating deep fakes of anything and everything — Heaven help us. And how are we going to survive in this increasingly Dunning-Kruger world, where the the people with the poorest understanding and weakest ability to reason are the very people who are most sure of themselves?

This is a subject that confounds me. I expect to talk more about it in future issues. It’s one of the most pressing issues of our time.

Axl Rose’s question

Axl Rose (who, by the way, stole my guitar — would you like to hear that story?) famously asked (in the song Sweet child o’ my-ee-eye-ee-eye-ee-ine) the pertinent question Where do we go-oh-oh from here? By which I think he might have been asking, Well, John, do you have any plans for following up on any of these threads in future posts of your ongoing autobiographical meditation called Sundman figures it out!?

To which I might reply, Well, Axl, thank you for asking. With particular regard to DNA and control of our (individual, group, human) genetic destinies, which are inextricably intertwingled with issues of corporate and governmental control of access to biological technology, bodily autonomy, biohacking, eugenics, extropianism, transhumanism and so forth: yes I do plan to address such topics future editions of Sundman figures it out!

Topics like deep-fakery and rabbit holes of delusional thinking, among others, will get their due as well.

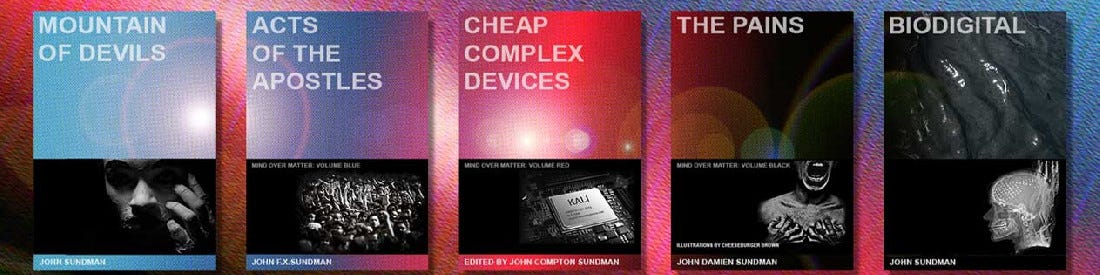

Meanwhile there’s my novels, of course. You can always buy one of my novels and immerse yourself in these moral-philosophical worlds presented in convenient thriller format.

And by the way, Axl, do you have any plans to return my guitar? It’s been nearly fifty years now. Can I have it back, please?

Accidental Samurai: How I became, despite my best intentions, a cyber-biopunk novelist, which I cross-posted on

’s substack deserves special mention. It generated a whole slew of new subscribers — who like cypberpunk! Memo to self: do more cross-posting!

Thoroughly enjoyed reading this. The idea that "we don't need 'experts' to explain complicated things to us — we can figure them out ourselves" is, indeed, a thing. I, personally, believe it and without any sense of conflict, ridicule others who do it. As Mr. Spock would say, "fascinating".

... and, of course. I really, really do want to hear about the guitar.

Great essay. Congratulations to Betty on ever being able to present at the Cold Spring Harbor Conference!