Happy New Year & screw you, 2024. Don’t let the door hit you on your way out

Running late, as usual. I had been planning to post this essay around December 28, but it refused to be completed until today, and so here we are, New Year’s Day, 2025. It’s not the kind of story I like to write but I feel compelled to even though it takes me on yet another detour from the stuff I really want to write about. I guess it’s fitting. “Everything ready, nothing works.” That’s the kind of year that 2024 was.

Welcome, new readers

Sundman figures it out! is an autobiographical meditation, in the spirit of Michel de Montaigne, of a 71 72 year old guy who lives with his wife in a falling-down house on a dirt road on Martha’s Vineyard that dead-ends into a nature preserve.

Incidents, preoccupations, themes and hobbyhorses appear, fade, reappear and ramify at irregular intervals. If you like this essay, I suggest checking out a few from the archives. These things are all interconnected.

Précis

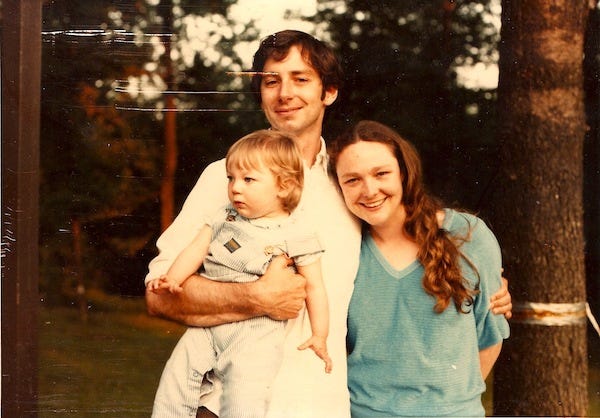

On the Saturday before Christmas, 2024, my 41 year old son Jakob was taken by helicopter from Martha’s Vineyard Hospital to Boston’s Brigham & Women’s, where, after what was evidently a pretty dramatic reception by the toxicology trauma team, he spent the next two days in the neurology ICU before being transferred to the less intensive care floor for two days and then being discharged on the 26th, after which I drove him back home.

Helicopter rides are one way to get from Vineyard to Boston; the more prosaic route involves a 45 minute ferry ride followed by a drive of about two hours. Because I am Jakob’s health care proxy and main advocate and was needed in Boston, and because I have other responsibilities on the Vineyard and was needed there, I had to do some back-and-forth. It was a complicated and stressful Christmas week for me — one of many such weeks over the last 40+ years, and one more week of no progress on the John Sundman, Famous Author front, oh well.

This post memorializes some of my Christmas week, 2024, and gives an account, with squirrel-brain commentary, of some of the other similar fun times in the past. Seasoned readers of Sundman figures it out! will not be surprised that it’s mostly an impressionistic jumble, not a linear account.

A Pazuzu Primer

As some readers will recall, Jakob was born with congenital toxoplasmosis, ‘toxo,’ a disease caused by a parasite incubated in cats, and because of this throughout his life he has had to deal with various inconveniences — some of them chronic, others acute; some of them life-threatening, others merely debilitating; some obvious, others quite subtle. In earlier SFIO! essays I have compared my own relationship to toxo to that of the archeologist/priest Lankester Merrin and the demon Pazuzu in the Blatty/Friedkin movie The Exorcist. For background on this disease and how it has affected my family since 1983, see either or both of my other Pazuzu essays:

As Tolstoy famously wrote, All families are the same, except those with toxo

Actually I think I may be confusing Leo Tolstoy with Helen Featherstone. Her book A Difference in the Family is an exploration of how the presence of a significantly disabled child changes family dynamics when compared to families who have only able-bodied children.

Featherstone’s son Jody was, like my son Jake, infected by the toxo parasite before he was born. Compared to Jody, Jakob got off lightly.

Jody was totally blind and couldn’t talk or move freely about; he died when he was ten years old. Jakob is only mostly blind; he does have some mobility challenges, but until recently he was able to get around quite well by walking and using public transportation; he’s not only able to talk, he’s quite articulate and will talk your ear off. Jody’s intellectual capacity was quite limited; Jakob has some quite particular and significant intellectual impairments, but in many ways he’s a smart guy. It wasn’t easy for him, but he managed to graduate from high school (it took him 7 years) and he lasted two semesters at Bridgewater State before flunking out.

In reflecting on their child’s disability, Featherstone writes in the introduction to her book, parents talk about four things: their own unhappiness; their family; professionals; the road to recovery.

I don’t know that I agree with that statement entirely. Do I talk about my unhappiness when this subject comes up? I certainly talk about stress, so maybe that counts?

In any event I found A difference in the family very helpful when I first read it nearly 40 years ago.

Jody and Jakob are quite different people, and Jody’s disabilities were much more severe than Jakob’s, but they were both infected by toxoplasmosis, that cat-shit transmitted parasite, before they were born, and much of what Helen Featherstone says about her family could have been written by me or Betty about ours.

Chapter 1 of A Difference in the Family is titled ‘Fear.’ So that certainly tracks.

Scene from a Pazuzu highlight reel

Late one afternoon in the summer of 1993 I crested the dune between the Atlantic Ocean and the streets of Beach Haven, with a surfboard under my arm, to find an ambulance and a police car and a crowd of people in the driveway of the house that my parents had rented for the annual Sundman family reunion on Long Beach Island, NJ (“LBI”). Jakob was ten years old and having a nasty seizure.

The surgery to place the plastic tube from his brain to his belly to void excess cerebrospinal fluid and prevent his head from exploding had only been done a few months earlier. Which, that operation was a good thing in that it kept Jake from dying, but ever since then he had been having occasional seizures. Before the surgery his most recent seizure had happened when he was about 18 months old.

In that Beach Haven driveway my wife & I briefly conferred & decided that I would be the one to ride in the ambulance with Jakob and she would stay with our two daughters. I put on a T shirt & some flip-flops and off we went, over the causeway to the hospital in Manahawkin, on the mainland.

After an hour the ER doc was ready to discharge Jakob, declaring him out of danger. But by this time I had witnessed a dozen of Jake’s seizures and I was becoming familiar with the varieties of his postictal states. I said, “No, I recognize this; he’s going to seize again.” The doctor said, “No, he’ll be fine,” at which point Jake howled like some kind of grizzly bear and had a massive convulsion. So the medicos held him down and gave him IV ativan but it didn’t help much, so the doc said, “We can’t handle this here. I’m going to send him to Camden.”

Camden, near Philadelphia, was about an hour away. I climbed into the ambulance.

I would have liked to call Betty to tell her what was up, but cell phones didn’t exist and I had no idea what the phone number was at the beach house and besides I didn’t even have a dime to put in a pay phone. There was no reasonable way for me to get in touch with her.

So, Jakob and I get to Camden, which was then the murder capital of the United States, and he is taken into the ER, and there are cops and metal detectors everywhere, and we eventually get connected with a neurologist, I wish I could remember his name. He was from Puerto Rico and had a bit of an accent. He was great — gets the seizure under control, Jakob is now finally sleeping, the doctor promises to keep an eye on him & says to me ‘go get some rest.’

Well, it’s 2 in the morning in the murder capital of the world and I don’t have any money and I’m wearing a wet bathing suit and damp t-shirt and flip-flops. ‘Getting some rest’ seemed a dubious proposition.

But somebody puts me in touch with a social worker and she tells me there’s a Ronald McDonald House there and she gives me a key and points me towards a house across the street and I open the door and shazam! I’m Dorothy, arriving in the Land of Oz and everything is in color. A nice clean house with 6 or 8 bedrooms1 and a stocked fridge and pantry and even some free clean clothes for me to change into, this actually happened, I was the only person in the house and had to wonder if I was tripping. I took a shower, ate a bowl of cereal and went to bed. It was the most miraculous thing.

The next morning Betty somehow found me at the hospital and Jake was discharged and we drove him back to LBI and soon it was time for me and Betty and our three children to go back to Massachusetts, as our vacation was over.

(And then of course there were years of hassle and confusion over the fee from the Southern Ocean Medical Center and the two ambulances and the hospital in Camden and miss-billings and claims denied and collection agencies calling me at work and all kinds of bullshit, never ending medical bill bullshit, I don’t want to bore you and where would I even start?)

Anyway the moral of the story is that if you ever go to a McDonald’s you should put your change into the little collection thing to support Ronald McDonald Houses, as they are life-saving and proof of human goodness on earth.

Here we are again

When I got to the Brigham’s trauma center two Saturday nights ago, three days before Christmas, I found Jake heavily sedated and intubated, with IVs in both hands and oxygen being pumped into his nose. There were three or four medical people in the room doing this and that. He was a high-priority, intensive-care patient.

“Ah Jakob,” I said to him. “Here we are again.” He, of course, couldn’t hear me.

Earlier that day I had been about to help Betty with some Christmas stuff — shopping, decorating, baking — I was doing all this stuff a week or two later than Betty would have liked; she wasn’t very happy with me — when I got a text from a friend who lives in the same apartment complex as Jakob does: “I saw an ambulance at Jake’s place & went over. He seems pretty lucid; I told the crew about his two recent surgeries. They’re taking him to the hospital now.” I assumed that Jakob had had a seizure, the usual, but certainly not the only, reason for him to take a ride in an ambulance.

So I drove to the hospital and after a little while I was allowed into the ER, where indeed Jakob seemed lucid, not in a confused post-ictal, state. When he has a seizure it’s usually because he has failed to take his medications on schedule, and when I got to his room he was earnestly explaining that he had not had a seizure, that he had taken his medications — that he himself had called 911, which would have been impossible if he had had a seizure. So what was the problem? “I fell and I couldn’t get up. My body wouldn’t let me.” Fortunately he he had been able to reach his phone, which he found on the floor next to him.

Now, in December 2017, five days after my retirement from Tisbury Fire Department, while he was still living in a group home, Jakob found himself on the floor and paralyzed. He was sent to Boston and had spinal (lumbar) surgery and spent 2 months in Spaulding Rehabilitation Hospital relearning how to walk. And then in August of this year something similar happened and he had spinal (thoracic) surgery and spent two months in a rehabilitation facility in Falmouth relearning how to walk, and so of course this most recent episode was a cause for concern: had yet another region of his spine given out? Was he experiencing stenosis again?

Blood was drawn & sent to the lab for tests and an X-ray was ordered and I was becoming convinced that he was just fine. He is, after all, still quite wobbly on his feet after his most recent surgery. His balance is not good. He fell and he couldn’t get up. Well, y’know, he’s recovering from stenosis. He’s still got a ways to go, months of physical therapy in his future. It’s not that surprising that he couldn’t get up.

But the ER doc, bless him, wasn’t convinced that Jake was ready to go home. He did the usual neurological tests of strength, coordination, reflexes — they were all fine. But he kept coming back to Jakob’s statement “my body wouldn’t let me get up.”

“Can you tell me more about your body not allowing you to get up? Can you describe the sensations?” Jakob, for his part, couldn’t find words to describe it. He just kept insisting that he had not had a seizure. “I took all my meds. You can check my pill box. It’s empty, because I took what I was supposed to take.”

I had been at the ER for about two hours, and the doctor was busy with another patient, when the proverbial light bulb switched on over my head.

I’m the person who fills Jakob’s pill box. It was Saturday afternoon. The pillbox should not have been empty until Monday night. I told a nurse that I suspected Jakob had overdosed on his antiseizure meds, and left to go check out his pill box myself. Eight minutes later I was at his apartment and sure enough the pill box was empty. Which meant that somehow over the last four and a half days he had taken eight days’ worth of meds. Ooops!

I drove back to the hospital where Jakob was now having a partial complex seizure, with his stiff legs rapidly rapidly opening and closing like a jumping jack on a string. And also, in a kind of frenzy, he was repeating over and over, “That’s the way it is. It’s not going to do shit! That’s the way it is. It’s not going to do shit!”

A nurse went to look for the doctor.

I’ve seen my son have lots of seizures over the years, but this one was the first time that he reminded me of Regan MacNeil when the demon Pazuzu was in her. It was freaky. The doctor came in the room and quickly sized things up:

Doc: Have you seen this kind of behavior before? Me: Nope. Never. Jakob [legs opening and closing faster and faster]: That's the way it is. It's not going to do shit! Doc: If he's OD'd on his meds he needs neurology and and ICU. I'm going to call Boston. After I find the best place to send him I'll call for a helicopter. Me: I'm going to go home & talk to my wife and collect some stuff. Meet you back here in half an hour. Doc: Good. See you then. Jake: That's the way it is. It's not going to do shit!

Right after the doctor told me that he had decided to send Jakob to Boston by helicopter, Betty called. She was expecting me to tell her that Jake was fine and would be going home soon. Instead I told her that he was going to be sent to Boston — which meant that I, as Jake’s medical proxy & main advocate, would be going to Boston too.

Now as it turns out Betty had learned that one of her friends, D______, a woman of some 95 years of age, had passed away the day before. Also, Betty has chronic pain from a failed operation on her back, such that things like grocery shopping are very hard for her to do without assistance.

“I’m in charge of refreshments for church tomorrow and they’re going to be doing something for D_______. Can you take me to Cronigs to get some stuff before you go to Boston?” I said, “Sure.”

It was about 4:15 PM when I left the ER at Martha’s Vineyard hospital for the second time that day. I stopped by the nursing station on my way out the door. “Can you get me a voucher for a spot on the ferry?” “Which boat are you aiming for?” “How about 6:15.” “OK.” “I’ll stop back here to pick it up around quarter to six.”

First I drove to Jake’s place to pick up the charger for his phone, then I went to my house to pack my computer and some clothes & my meds and a notebook, then I drove Betty to Cronig’s Market where she & I together did some speed-shopping for food for after the church service, then I went home and helped Betty with one or two other things, and I walked our dog Spot. Overhead I heard a helicopter as I walked her. I headed back to the hospital. I was in Henry Hill (Ray Liotta) mode from the helicopter scene in Goodfellas.

When I got back to the ER at Martha’s Vineyard Hospital the helicopter crew was already there and Jakob was no longer having a partial complex seizure — out of the corner of my eye I could see that he had progressed to a full tonic-clonic seizure with whole-body convulsions, and, after the convulsions stopped there was lots of aggressive flailing around and roaring like a cornered wild beast. Sometimes in this postictal state he can become quite violent and has to be tied down with restraints.

I collected the form I would need to get a reserved spot on the sold-out ferry and went to the room where Jake was.

Including the crew from the helicopter, the ER doctor and a few nurses who were holding Jake down there were about eight people in the room. I put my hand on Jakob’s leg. I said, “Jake, I’m here. I’m leaving now. I’ll see you in Boston. Be nice to these people. No more of this grizzly bear bullshit.”

As I left the room the doctor put a friendly hand on my shoulder. He said nothing, but simply nodded.

I made it onto the boat with about 5 minutes to spare. Went upstairs to get myself a hot dog & cup of chowder. Took them back to the car on the freight deck where I wolfed down my supper as the whistle sounded while the boat left the slip and the 45-minute crossing began. Put the seat back and pulled my hat over my eyes for a nap.

I was just dozing off when my cell rang. A nice doctor from the trauma center at Brigham & Women’s: “I just wanted to let you know that the helicopter crew requested that Jakob be sedated for his safety during the flight. So he’ll be unconscious and with a breathing tube down his throat when you get here. Don’t be alarmed. This only a precaution; his condition has not deteriorated.”

“Thank you, Doctor,” I said. “I was expecting that. We’ve been through this before.”

Saints, heroes, outcasts, freaks

Featherstone:

Each child is different; no child’s future is assured; and all parents fear for themselves and their children. All families must learn to live with anger, both justified and unjustified; with uncertainty; and with the inevitable. Raising children, especially when they are small, is a lonely business[. . .]. Guilt for a child’s unhappiness and shortcomings plagues parents of every stripe, whatever they may say to friends and relatives. Even the best-endowed child strains his or her parents’ relationship. A disability only intensifies the strain, as it does other family problems.

I stress the parallel between disability and relatively ordinary family ills for two reasons. One is to correct the view of those who perceive beleaguered parents and children as saints or heroes, outcasts or freaks. The second is to show families with disabled children that their difficulties differ only in degree from those of other families. In coping with their extreme situations they share with all families the heroism of coping with whatever life offers.

So we go on

Sometime around midnight on that Saturday night, Jake was transferred from the trauma center to the neurology/neurosurgery ICU. I left and drove to a hotel out in Watertown not far from Perkins, formerly known as Perkins School for the Blind, the residential school that was Jakob’s primary home from when he was 14 until he was 22. It was really, really cold that night; coldest night so far this winter.

The next morning I drove along the Charles River from Watertown to Cambridge en route to Boston, passing a playground where I had spent a cold drizzly morning nearly four years ago with my two granddaughters, ages 3 and 5, while their mother, my older daughter, was at Children’s Hospital in Boston, visiting her 7 year old son. He spent nearly a month there, while I cared for his sisters. I couldn’t help thinking about how when my daughter was young, she and her sister accompanied Betty to Children’s when their brother Jakob was hospitalized there.

Between December 22 and 26 I made three round trips between Martha’s Vineyard and Boston. I spent two nights, including Christmas, in Boston area hotels, and on the 26th I drove Jakob home. He’s fine now. By some definition of fine. Until I come up with a better solution I’m filling up his pill box one day at a time.

Like me, Jakob’s kind of apprehensive about all the noise Republicans are making about ending Social Security. Will his check, his only source of income, stop coming? Will mine? Ah, well, the inauguration is still almost three weeks away. Let’s not worry about that yet.

The surfing/Ronald McDonald House story, the Jumping Jack seizure/helicopter ride story, might sound a bit dramatic, exaggerated, over the top. But they’re true, and moreover I assure you that I have dozens more stories like them, several of them even more intense. Some of these stories are funny or dramatic — life and death, hanging on by a thread, if not for the courage of the fearless crew the minnow would be lost, blah blah blah — amazing stories full of improbabilities; portentous, even — and some of these stories are quite painful. I don’t know if I’ll ever tell them. On the one hand they might be interesting, and on the other hand, what’s the point. Jakob doesn’t mind me writing about this stuff, Betty finds it mildly interesting — but I wonder how Jakob’s sisters feel about it. It’s not like they were somehow not affected by all this.

I’m 72 and Betty is 75. It gets wearying. But we’ll go on, just as you will, heroically coping with what life offers.

I’m not sure what my next SFIO! essay will be about, all I know is that it will be as far from this topic as I can get.

Cheerio!

According to the website, the original Camden Ronald MacDonald had 10 bedrooms in “a modest Victorian row house.” The new Ronald McDonald house in Camden has 25 bedroom suites.

An uncle of mine, similar age to yours, just had to deal with a similar situation with his own son (who had a motorbike accident that left him in permanent poor health and pain).

It is humbling to see parents in their 70s being this heroic.

I remember visiting a Ronald McDonald House years and years ago when I was with my mother accompanying her friend to a hospital for something to do with he daughter. We didn't stay there (my mother's friend did for a while - if I recall correctly), but you're 100% correct that they deserve every penny that gets donated to them.