Toxoplasmosis, my Pazuzu. Part 2

How we met the demon

An update on Jakob’s status as of Monday, September 9, 2024

In my earlier post Toxoplasmosis, my Pazuzu, Part one, I described a health crisis recently experienced by my son Jakob. Here’s the latest:

On Thursday, August 29, 2024 Jakob underwent surgery at Boston’s Brigham & Women’s Hospital to address a compressed spinal cord in the neck region of his spine. After the surgery was complete the surgeon told me that the operation had been ‘wonderfully boring’ and that he expected Jakob to make a rapid and complete, or nearly complete, recovery. Jake is currently staying a rehabilitation facility in Falmouth, where he’s getting physical and occupational therapy. Using a walker he can walk several hundred feet every day. His balance is not good, but it is improving. The staff estimates that he’ll be strong enough, and stable enough on his feet, to go home in about ten days or so.

Before he gets home I’m going to have to find time to clean up his place. Jake has never been one for fastidious housekeeping, and now that his vision, always poor, has recently gotten much worse, and in light of his recent adventures with being unable to walk, well, I guess I’ll have to find a hazmat suit and deal with the situation.

And then, as soon as possible after that, we’ll need to schedule a pre-operative visit to his eye surgeon.

New here? Welcome

Sundman figures it out! is an ongoing, interwoven autobiographical meditation, with incidents, preoccupations, themes, etc that appear and interact at irregular intervals. If you like this essay, I suggest checking out a few from the archives. These things are all interconnected.

Précis & recapitulation

This is the second post in series that began with Toxoplasmosis, my Pazuzu, Part one.

In Part one I compared my relationship to toxoplasmosis, the disease caused by the cat-incubated toxoplasma gondii protozoan parasite, to the relationship between the Jesuit (Catholic) priest Lankester Merrin, SJ, and the demon Pazuzu in the Exorcist movies.

I wasn’t even sure I was going to write a Part two. This stuff is personal, and involves talking about things that are private to people other than myself. But, having talked it over with Betty and with Jake, I’ve decided to go for it. I don’t know how many essays it’s going to take to tell the whole story — I’m guessing 4 or 5 — but having decided to do it, I’m going to try to do it right. It’ll just take however long it takes.

There’s no reason anybody might find the basic story — a guy has a child who has disabilities and medical challenges — especially interesting. We all have our worries, after all. But this Toxoplasmosis, my Pazuzu series — however long it may become — isn’t going to be just a long tale of one family’s medical crises and stresses. Like most Sundman figures it out! posts, this essay hops around thematically and temporally. But, as with other SFIO! stories, it includes cosmic coincidences and surprising connections that ramify over decades. I expect that some parts of this story are going to amaze you.

In this second issue of Toxoplasmosis, my Pazuzu, I start by giving some of the context in which Betty & I began our lives as parents of a medically-challenged child. I then go into more detail about our son Jakob’s early medical history — his having been born prematurely with a raging toxo infection that went undiagnosed and untreated for more than a year — and I talk a bit about how these things affected me and my family.

Here in part two we also see the beginnings of the transformation of a somewhat introverted molecular biologist — a woman who was most happy when working by herself in laboratories full of test tubes and shaker-trays and liquid-nitrogen freezers quietly unravelling mysteries of DNA — into a fearless exorcist willing to take on anything and anybody — be it demon, protozoan, bullies, clueless teachers, institutional inertia or self-regarding asshole doctors — to protect her son.

By the end of this Toxoplasmosis, my Pazuzu series you’ll know the story of how Betty, (whose scientific work I’ve mentioned in a few earlier SFIO! posts), had not only secured the best available therapy for our son, but also helped to bring about changes in the detection and treatment of toxoplasmosis that would improve the prospects of every child born with congenital toxoplasmosis in the United States of America.

Teaser: Don Berwick for Governor

This is a photo of me wearing the t-shirt I was given as a Berwick delegate to the 2014 Massachusetts Democratic Party convention, in Worcester. At the convention, Berwick gained enough votes to make it onto the Democratic Party primary ballot. In the primary, the Democratic voters of Massachusetts, in their great wisdom, chose Martha Coakley, then best known as the Senatorial candidate who lost to Republican Scott Brown, a man with the charisma of a bag of wet gym socks. In the gubernatorial election she lost to Republican Charlie Baker, a similarly charismatic fellow.

We’ll come back to this topic in a later installment of Toxoplasmosis, my Pazuzu.

Pazuzu comes to Westboro

In May, 1983, Betty and I and our daughter J____, were living in the house across the street from the vast and mostly empty campus of Westboro State Hospital, which used to be called an ‘insane asylum’.1 I was working as a junior technical writer at Data General, my first job in the computer industry; Betty had a job doing research on bacteriophage at Tufts University Medical Center in Boston. Our daughter was 27 months old months old.

The house was a wreck when we bought it in 1981. There was a dead car on blocks in the yard and bags of garbage near the collapsing back porch. The house had been burned in a fire; a newlywed couple with a young child — a mirror image of me and Betty — had bought the burned shell and had half-finished rehabbing it. But it was too much. They gave up and got divorced.

When we arrived at the house after the closing I realized that we didn’t have a key to our new home. So I kicked the door in & carried Betty over the threshold as a proper husband should do with his bride. That door was a piece of junk anyway.

Betty & I both worked to exhaustion and beyond: rehabbing that house, doing our day jobs, taking turns doing parental duties — hardly even seeing each other longer than it took to hand our daughter off to to the other parent, it seemed. I did the hammering and sawing and electrical stuff; Betty painted the walls and made curtains. But somehow we must have seen each other socially at least once in a while, because she became pregnant again when our daughter was a year and a half old — right about the time the above photo was taken.

During the pregnancy Betty developed some lumps near the base of her skull — we later figured out that they were lymph glands fighting a toxoplasmosis infection — but her OB/GYN told her it was nothing to worry about. When she was in her 7th month I somehow had re-aggravated an old injury, and my entire upper back became one constant spasm. The pain was excruciating — even walking up the stairs to our bedroom was too painful, so we had somehow gotten a mattress on to the floor of our living room. I could barely perform my day job — the pain was too severe — but I had used up all of my sick days.

So it was inconvenient when Jakob announced his intention to come into the world more than six weeks ahead of schedule. Waking up one morning in a soaked bed, Betty tried to convince herself that it was so wet because she had peed herself. But I performed a quick smell and taste test. “That’s not pee, darling. Your water has broken.” She started to feel contractions.

Thank heavens we had a next door neighbor who was able to babysit. My back spasm kicked it up a notch; I couldn’t drive. I lay on on my back in the back seat, while Betty, who was now clearly in the early stages of labor, drove us to Boston.

At the hospital we got a quick lesson in premature birthing. Tests were done. How mature were the baby’s heart and lungs? Was the liver able to process bilirubin? Any sign of kidney failure? A dozen other things. To distract us from our worries while waited for test results I bought some magazines Mister T on the cover. Betty was given drugs to slow down the labor, and then something changed, I don’t remember what, and the decision was made to induce labor, to get the baby out ASAP, and she was given drugs to speed up the labor.

At one point during all this stressful hubbub, a social worker took us to a quiet room, and, after giving us a quick education in all things preemie, told us, as delicately as she could, that many babies born this early, for whatever reason, didn’t survive. Would we like to consider purchasing burial insurance? No, we wouldn’t. After she left, Betty & I just stood looking at each other for a long time.

Betty said she had had a premonition or a dream that this baby had to be born before midnight or her supply of good luck would be used up. It now became very important to her that the baby come on that day. That day, she insisted. Not tomorrow.

Jakob arrived five minutes before midnight.

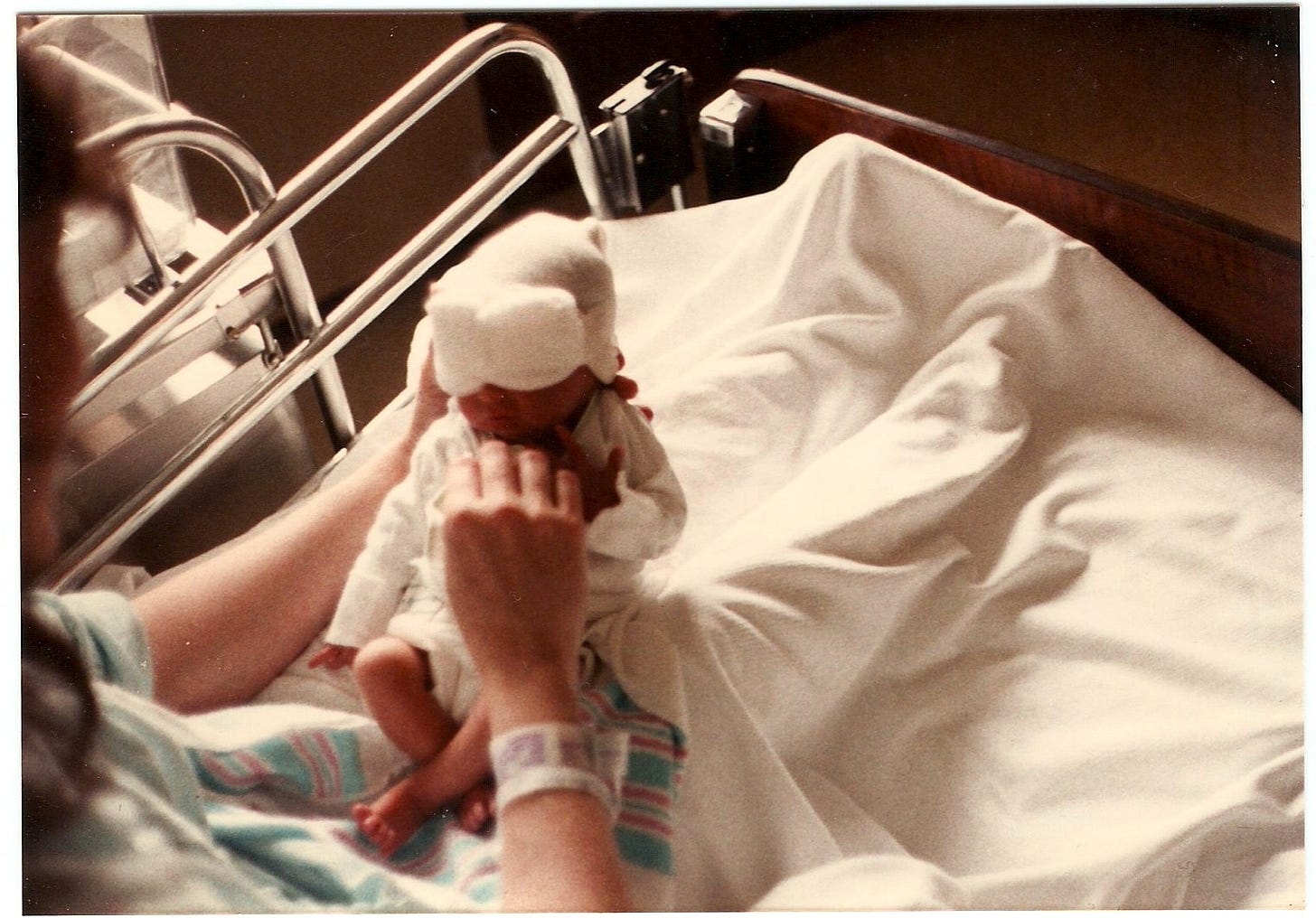

He was taken straight to neonatal intensive care, but some time later (hours? days?) she was allowed to hold him.

At home alone I took a couple of illegally obtained quaaludes with a shot of tequila. Fortunately, I didn’t die. The spasm in my back lifted for the first time in weeks. It worked a lot better than the hot showers my useless doctor had prescribed.

A snapshot of The Man from La Brea

My son Jakob is a man of conflicting abilities and attributes. When he was in eighth grade he took a battery of cognitive development tests over a two day period that showed a range of aptitudes from kindergartner level (spatial reasoning, problem solving. . . ) to college level (verbal skill, reading comprehension). Although I don’t believe Jakob has ever been diagnosed as having autism, he describes himself as autistic. He says he has a hard time parsing emotions — his, or anybody else’s. To me and Betty, Jake’s emotions always seem restrained. He experiences happiness and he has a quick wit; he smiles a lot and he likes jokes and funny movies. But he rarely laughs. His positive emotion pegs at ‘amused.’ Similarly he experiences frustration and annoyance and resentment, but not anger. He doesn’t like loud things. He has never raised his voice, ever.

In addition to generally poor vision, he also has face blindness, such that, for example, he does not know me or Betty or either of his sisters by our faces; he recognizes us by our voices.

The only job he’s ever had that he both loved and was good at was being a greeter at the Wal-Mart in Falmouth, to which he commuted by three busses and a 45 minute ferry ride, a total of two hours in each direction. Wal-Mart terminated his position when his spine collapsed in 2017 — I guess the corporation couldn’t afford his minimum wage salary — and he has been ‘looking for work’ since 2018.

He knows things, lots of things. He always has. At a family gathering when he was eight years old he astounded my brother Michael by making some kind of observation — I don’t remember the subject — perhaps it was something about the difference between Jungian and Freudian views on dreams? Or maybe it was the something said by a delegate from Delaware to the 1787 Constitutional Convention? It could have been anything. While I don’t remember the topic I do remember this part of their conversation:

My brother: Jakob, that's amazing. How did you know that? Jake (8 years old): Uncle Mike, my brain is like the La Brea Tar Pit. Things go in there and they don't come out.

Nervous mother syndrome

After Jakob had been discharged from neonatal intensive care and he had been home with us for a few weeks it became clear that he had no real interest in being here among us living people. He never moved. He never cried. He never ate. He never did anything. We held him, and hoped, and worried.

He barely nursed. Every night I would get up at three hour intervals to try to get him to drink some of the milk Betty had pumped from her breast and frozen in a little glass baby bottle that held 2 or 3 ounces. I’d warm the bottle in a pan of hot water, then try to wake Jakob by rubbing an ice cube on the sole of his foot to see if I could get him to suck the little rubber nipple. Sometimes that worked, but mostly it didn’t. Sometimes he’d drink half an ounce or so, then drift off. . .

Our two year old daughter had spent the first week after Jakob was born with my parents, and when rejoined us it seemed that she had picked up on our worries. I think she was traumatized, frankly. She woke up crying every night — screaming — punctually at 11:00. Sometimes I rocked her for more than two hours before she went back to sleep. Often she woke again at 4 AM, crying.

Faced with this new reality, Betty resigned from her position at Tufts Medical Center as a research scientist studying the structure and function of viruses that infect bacteria. Before we moved to the Boston area, she had worked in a lab at East Carolina University Medical School, doing research that contributed to the first pediatric vaccine for H. influenza. Now she was a full-time mother. She was never to work in a research lab again.

But Betty was still a scientist. She kept a chart of Jakob’s weight and all of his milestones. She drove him into Boston, repeatedly, to see the pediatrician, taking our two and a half year old daughter with her.

Betty: What is wrong with this child? There must be some underlying condition. Doctors: He's just premature. Preemies often develop slowly. He'll be fine. Betty: He doesn't react to stimuli. His eyes don't work together. My husband and I are not even convinced that he can see. Doctors: Be patient. Betty: He has constant ear infections, constipation and diarrhea, low-grade fever. I've plotted his growth on log-linear graph paper. He's two standard deviations below normal, even for a preemie! Doctors: Diagnosis: Nervous Mother Syndrome

Eventually Jakob was referred to pediatric ophthalmologist who prescribed eyeglasses and an eye patch to treat strabismus and amblyopia (misaligned eyes, wandering eye). The doctor wanted to put Jakob under anesthesia to get a better look at his eyes — it was hard to get a good look with all that nystagmus (twitching eye) going on, not to mention Jakob’s photophobia — but for the first year of his life Jakob was too frail to risk it.

Finally he was deemed strong enough. During the exam the doctor saw Jakob’s retinas — he must have known immediately what he was looking at, but he ordered a blood test that confirmed it. Betty and I heard the result, having no idea what it implied, and drove our son home. On the way home we stopped at Henry Bear’s Park and bought a bunch of colorful toys. Jakob had no interest in them.

But at least our Pezuzu finally had a name: congenital toxoplasmosis.2

Our pediatrician, the one who had given Betty the diagnosis of ‘nervous mother’ syndrome, now told us not to worry. Yes, Jakob’s eyes had been damaged while he was a fetus, and the toxo was also probably responsible for Jakob’s premature birth, and also all those other minor inconveniences that Betty had been going on about. ‘Failure to thrive syndrome’ and all that. But smile! That’s all in the past! The future is bright!

It would have been nice to learn more about the disease, but in those pre-internet days it was extremely difficult to find anything out about it. There was no “Toxoplasmosis Foundation” or anything like it; no pamphlets in the doctor’s office. People relied on doctors for medical information because they had no choice.

A chance meeting, a library card, a revelation

When we lived in Westboro we became friends with Leigh E______, who was, at the time, head of nursing at U Mass Medical Center in Worcester. Some time after we had received Jakob’s diagnosis we moved to Gardner and fell out of touch with Leigh. But one day Betty happened to run into Leigh at the hospital in Worcester (perhaps when she was there trying to get help for our now 4 year old daughter, who still had night terrors and and rarely slept an entire night without crying), and Betty told her about Jakob’s toxoplasmosis.

Long story short, a few days later, while I watched the children, Leigh used her badge to get Betty into the hospital’s library — where non-medical people were not allowed; this was a Mission: Impossible kind of deal — and there Betty found (a much earlier edition of) this book:

The chapter on Toxoplasmosis, nearly 90 pages long, was written by Dr. Jack Remmington, MD, PhD, a professor at Stanford Medical School, in Palo Alto, California. Betty somehow copied the whole chapter on the library xerox and smuggled it out of the building.

That night, as I tried to sleep after a long day at the office writing documentation about operating systems, array processors and a faulty floating-point board, Betty sat up in bed next to me reading Remmington’s chapter on toxoplasmosis.

When she got to the part about adverse sequelae, around 3 AM, she shook me awake, and read to me a list of one horrible condition after another that in later years afflicted children born with toxoplasmosis and who, like Jakob, had never gotten treatment for it.

Forty years on I can still hear her shaking voice. “Oh God, John. Our baby is in so much danger. Oh my God. Oh my God. Oh my God.”

The next morning she made a phone call.

“Hello Stanford University Medical Center? I would like to talk to Dr. Jack Remmington.”

To be continued. . .

Actual experiences that I had with “crazy” residents of that institution are reflected in my novellas Cheap Complex Devices and The Pains.

We have no idea how she got infected. She’s very allergic to cats. Perhaps she got it while gardening. Perhaps a cat had used our daughter’s sandbox for a place to poop? It’s unknowable.

This is hard to read, but I feel like I need to read it as much as you need to tell it.

Thanks so much for all you're sharing....wow, I figured you folks must've gone thru a lot, but had NO idea :( . You put it so well....the 'grin' Jake would have, tho he did chuckle a few times in 8th grade at some jokes he shared. Looking forward to more that you'll be sharing, to learn more of the story and it's truly a 'family' story, as it's in it's 'own way' had an affect on everyone of you. Hugs to all!