Toxoplasmosis, my Pazuzu. Part one

The old demon is back in town. So far, it has fucked up my August. September, TBD

Prologue & précis

In the opening scene of Willian Friedkin & William Peter Blatty’s awesome horror movie The Exorcist, Father Lankester Merrin, a Jesuit priest and archeologist, is on a dig in a hot, sandy, windy Iraqi desert when he comes upon a statue of the demon Pazuzu. A look of horror comes on Merrin’s face. Although we, the viewers of the movie, don’t understand the exact significance of the find, we know it’s not good.

August was a turbulent month for me. All my plans got blown to smithereenies; I was OBE & SOL, 'overcome by events & shit out of luck'. Didn't post a substack essay for an entire month ( in a typical month I publish 3 or 4). So now I'm writing this one just to make a record & clear my head.

It turns out that many years ago Fr. Merrin had performed an exorcism in Africa, casting Pazuzu out of an innocent’s body. When Merrin sees the statue of the demon a thousand miles, and decades removed, from that encounter, he recognizes it for what it is: a calling card — Pazuzu’s way of telling Merrin that’s he’s back in town.

There’s an unthinking, unrelenting, malevolent entity that pervades the the account of the last thirty days that I’m going to attempt to give in this essay, and its name is congenital toxoplasmosis. I sometimes think of toxoplasmosis as my own personal Pazuzu.

Teaser: my son the robot

Just under seven years ago, on December 5, 2017 — five days after I turned in my pager and began my mandatory retirement from the Tisbury, Massachusetts (volunteer) Fire Department — my son Jakob, who was then 35 and residing in a group home managed under the auspices of the state’s Department of Mental Health, awoke to find his feet numb. Mere hours later he was unable to feel or control anything below his chest. He was sent by ambulance from Martha’s Vineyard Hospital to Brigham & Women’s Hospital in Boston. I followed in my car.

After lumbar spinal surgery for spinal stenosis & 6 months of hard work — including a two-month stay at the world-class Spaulding Rehabilitation Hospital in Charlestown (Boston) — and with lots of help from many people, Jake recovered about 95% of the functional mobility he had before his spine collapsed. Until a few months ago it was not unusual for him to walk five miles in a day.

Then something happened.

My original plan for August, 2024

Before I found my August blasted to ruins lying all bluely about me, these were some of my intentions for the month:

Complete the draft of my forever-in-progress novel Mountain of Devils, the prequel to both of my nanoscopically famous hackertastic novels of technopotheosis — Acts of the Apostles and Biodigital;

Launch my substack-hosted podcast The Desired Effect, with the inaugural episode to be an in-depth interview with the legendary science fiction grandmaster and 2024 WorldCon Guest of Honor Ken MacLeod;

Prepare, at long last, the new editions of my four existing books and make them available for purchase in paperback & ebook formats from Amazon & other outlets, including indie bookstores and directly from me;

Resume regular exercise in Gymnasium Pandemica, the backyard facility I built when Covid shut down the weight room at the Tisbury Emergency Services building.

I accomplished none of those things — although I did, however, conduct a great interview of Ken MacLeod. You’re going to love it if I ever get it edited & posted as a podcast.

Congenital toxoplasmosis

Excerpts from the helpful Boston Children’s Hospital toxo backgrounder:

What is congenital toxoplasmosis?

Toxoplasmosis is a disease caused by the parasite toxoplasma gondii.

If the parasite infects a pregnant woman, it can enter the placenta and affect the baby inside.

The parasite usually enters the body through the mouth. It can be spread in two ways: eating uncooked or undercooked meat or eggs containing the organism, or by oral contact with either soil or cat feces containing parasite eggs (e.g., gardening in infected soil or handling cat litter or feces and then putting your hands in your mouth).

Cats are the only animals that can transmit the toxoplasma gondii parasite directly to people (and only through their feces), but there is no documented correlation between cat ownership—especially if the cats are kept indoors—and toxoplasmosis.

What are the symptoms of congenital toxoplasmosis?

Many (up to 90 percent of) babies born with congenital toxoplasmosis experience no immediate symptoms. However, one sign of infection is a premature birth or an abnormally low birth weight.

As an infected baby grows, more signs and symptoms can appear. These may include the following:

Toxoplasmosis can also cause some more serious problems, including the following:

retinal damage

hydrocephalus — a buildup of cerebrospinal fluid in the brain

intracranial calcifications — these indicate areas of the brain that have been damaged by the parasite, and are often linked to the following conditions:

intellectual disabilities

motor and developmental delays

hearing loss

This kind of information was nearly impossible to find in 1983. About which more later.

By the way, Jake has experienced all of these symptoms except hearing loss and enlarged liver or spleen. And I’m actually not sure about the hearing loss. I should look into that.

A house for Mr. Jakob

I live with my wife Betty in Vineyard Haven (Tisbury) on the island of Martha’s Vineyard, south of Cape Cod, Massachusetts. Our son Jake, after he graduated from Perkins (then known as Perkins School for the Blind) at age 21, managed to survive two semesters at Bridgewater State University before flunking out. (The more you learn about Jakob, the more impressed you’ll be by that accomplishment.) After staying about a year with us, Jakob moved to the group home in Oak Bluffs, about 4 miles away from our house. He lived there for about 12 years before finally —about 4 years ago — achieving one of his longest-held goals: getting an apartment of his own. He has a place at Hillside Village, about 1/4 mile from my house.

At the group home, the staff had helped with things like supervising administration of Jakob’s anti-seizure medications and scheduling ( & arranging transportation to) doctor appointments (both on- and off-island). When he moved to his own place he still had some support available, but after a few incidents (seizures, missed appointments) Betty & I came to the conclusion that Jake could use our help. Somewhere along the way he also signed a form authorizing me to be his medical proxy.

A visit to the retinologist

Like virtually everyone born with congenital toxoplasmosis, Jakob has severely damaged eyes. When I discovered that he had not seen an ophthalmologist in more than two years, I made an appointment with a retina specialist in Falmouth for July 30th, and made a ferry reservation.

The retinologist took a good look and said, “well the left eye, probably nothing can be done with that, but before I can tell what’s going on with the retina of the right, we’re going to have to get that cataract removed and a new lens put in. Immediately.” Then she picked up her phone and called two of her associates: Dr R___, in Boston, who specializes in toxoplasmosis, and Dr. H__, a cataract surgeon in Weymouth. Jake was given emergency priority; I made two more ferry reservations. We went to Boson on August 1st and Weymouth on August 2nd.

The toxo specialist in Boston said, “I can’t tell what’s going on. We need to get that cataract fixed in order to see the retina.”

The surgeon said, “very challenging; I want Jakob to be seen by another of our colleagues, in Plymouth.” I made another reservation.

[Ferry tickets for island residents this time of year cost $104, by the way. Our trips off-island had cost me more than $800. My wife & I have no savings (long story). We don’t have $800+ of slack in our monthly budget.]

Surgery was scheduled for September 3rd. I scheduled an appointment with Jakob’s primary care doctor for a pre-surgical clearance on August 20th.

On August 18th I got a call from a doctor in the Martha’s Vineyard Emergency Department. Jakob had been taken there by ambulance after being discovered lying on the ground outside his apartment, his face bloody, after an apparent seizure. I went to the E.R., found Jake mostly alert, but perhaps still a little dazed, a bit foggy, a little post-ictal. That phase can last any where from twenty minutes to a day or more.

So the question was, why had this happened? When Jake has a seizure, it’s almost always because he has missed taking his meds for a day or two. But he swore he had taken his meds that morning. I decided to drive to his apartment to get some clean clothes for him, and to check his medicine box to see if I could determine whether he had, in fact, taken his prescribed medications.

His apartment looked like a scene from CSI. Big pools of congealing blood on the floor near his bed. I cleaned it up. To the best of my ability to determine, he had in fact taken his meds. A mystery: if he had taken his meds, why had he seized? Was there something new going on?

Back at the E.R. Jakob was very wobbly on his feet, not able to safely walk unassisted. I said to the medical staff, “it’s OK; he gets like that sometimes when he’s post-ictal.” We took him to my car in a wheelchair. At his apartment I got his wheelchair — he hadn’t needed to use it for six and a half years — and got him from my car to his bed.

August 19th I got a call from one of my friends on Tisbury Ambulance, “Hi, John. We have Jake, he fell on the sidewalk near his house and somebody called us. He’s not able to stand, but he’s refusing to go to the hospital. Can you come get him?”

I took him home. I noticed he was looking much skinnier than he had just 3 weeks earlier when I was taking him to Weymouth, Boston, Falmouth and Plymouth. The next day I took him to his scheduled primary care doctor pre-surgical checkup. We didn’t use the wheelchair, but I held him up as he walked. Doctor said, “he needs to see his neurologist.”

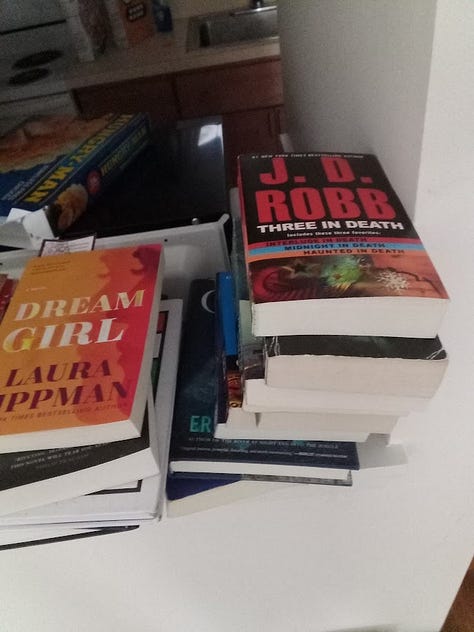

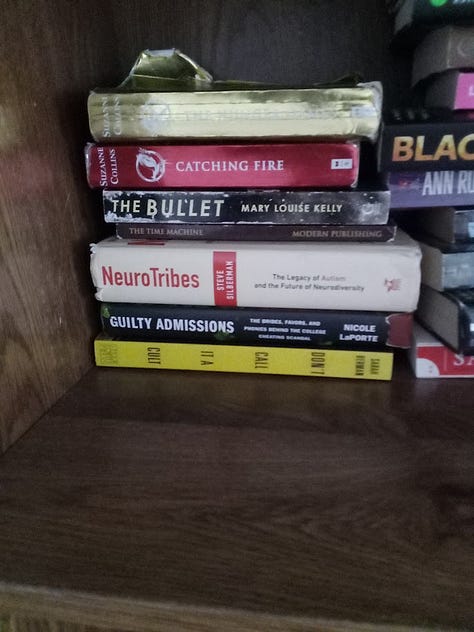

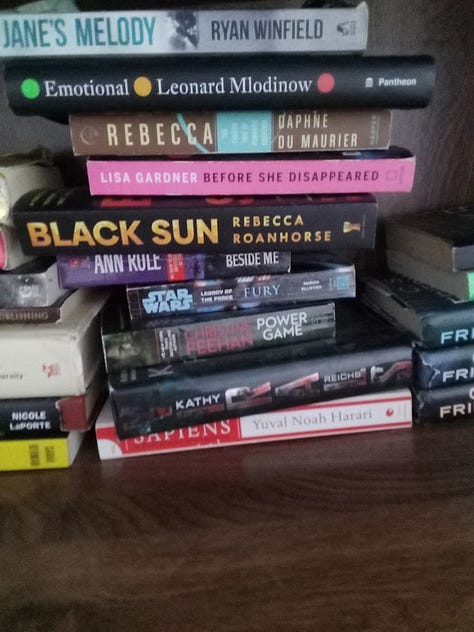

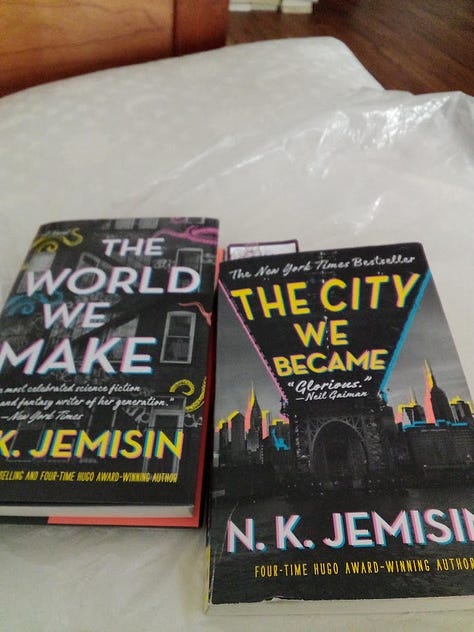

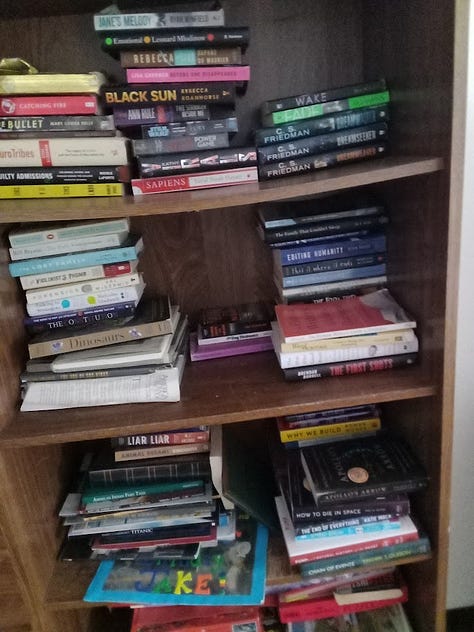

Over the month of August Jakob’s vision had deteriorated to the point where he could no longer read. To understand the significance of this, see these photos from his apartment. He is a bookaholic and compulsive reader, and never goes anywhere without his book bag, containing up to ten books.1

On the way back to his apartment from his primary care doctor, we went by the Stop & Shop to get some food. I said, “It’s not safe for you to use a stove. We’re going to get you some frozen dinners.” He was leaning on me to walk. As we crossed the parking lot his pants fell down — that’s how much weight he’d lost. “I didn’t have any money for food,” he told me. He spends all his money on books.

I sent a note to his neurologist, describing all this. I added, “I lived with my brother Paul for six months when he was dying of ALS. I don’t like the looks of this.”

She had been off line for two days, but called me on the phone when she got my note: “I want him in Boston, ASAP. Take him to the Martha’s Vineyard Hospital E.R. & they'll send him up by ambulance.”

It was Friday morning, August 23.

I called Jakob to tell him the plan. He was annoyed with me for keeping him out of the loop. I didn’t tell him that I was terrified that he might have ALS, and that’s why I wasn’t telling him everything I was telling his doctors. Then he told me, “I just got a call from the retina doctor. She told me that she & the cataract doctor have decided that my cataract is too complicated for him to do. So she’s going to do the surgery. So now we need to schedule another visit with her before the operation.” I picked him up ten minutes later and drove the two miles to the hospital.

We spent 8 hours in the Martha’s Vineyard ER. Turns out that they don’t just call an ambulance for you because your neurologist told you to come to Boston. They have to make their own determination, of course. Finally, around dinner time, emergency room doc says, “we agree he needs to go to Boston, but there’s no ambulance available. We can call for a helicopter, or you can drive him.” Jakob’s already had two life-flight trips. He doesn’t need another one. “I’ll drive,” I say. I manage to scare up enough $$ for the ferry ticket and gasoline.

We got to the neurology ward at Brigham & Women’s around midnight, completed the handoff around 1:00 AM. See you tomorrow, Jake.

I don’t have enough money for a hotel room, and none of my Boston friends have replied to my inquiries about a couch upon which I might crash. Looks like I’ll be sleeping in the car tonight.

I pull in to the parking garage, find the darkest corner I can (between two other cars where I’m hoping I won’t be noticed), put the seat all the way back, cover myself with a blanket, get ready to pull my hat over my eyes.

That’s when I notice the guy walking around the car that’s parked 2 spots down from me. What the hell is he doing there at one in the morning? He’s just standing there. Now he’s gone over to a concrete pillar and I think he’s taking a leak. What’s going on? Is he another guy sleeping in his car? Or is he one of those people who smash windows & grab stuff? He’s making me nervous. I’ve already been jumped and knifed in Boston; that time everything worked out more-or-less OK but it’s not the kind of experience I that I really want to do again. Wait, did he just open the trunk of his car? I can’t tell — I’m looking through the windows of the two cars between us — and also, for some infernal reason it’s very loud here, so if he did close the trunk I wouldn’t be able to hear it. I slink further down. After about ten minutes of standing near the car he finally walks away. Phew.

I’ve got about $30 on me, probably enough to cover the parking. Maybe get a cup of coffee in the morning. Maybe I’ll have enough for a donut too. Whatever. I’ll figure something out.

Before I drift to sleep I mutter to my companion in the shotgun seat:

“G’night Pazuzu. See you in the morning.”

Intermission: A visit to the Department of Adult Vegetables

One of the few areas of overlap between my planned activities for August, 2024 and what I actually did was go with Betty to the Martha’s Vineyard Agricultural Society Fair in the middle of the month, where I took this photo in the Ag Hall.

Sometimes, I swear to Fred, I think I should just find that department and ask for an application to join.

‘Loss of consortium’ at the Martha’s Vineyard Airport Laundromat

A few days ago I mentioned to Betty that I was struggling to come up with an essay for Sundman figures it out! — that in fact I was in the longest essay-drought in SFIO! history.

Dear Wife: Are you writing about what's been going on with Jake? Me: I can't avoid it, but I hate reducing our son to a list of his ailments and the inconveniences they've caused us. DW: Well, that is our life. A big part of it, anyway.

Nearly 30 years ago, not long after Dear Wife & I had decided to flee from the one year we spent living in greater Silicon Valley after I got laid off from Sun Microsystems — the year Jake was ten years old and his head nearly exploded from hydrocephalus but didn’t due to a ‘semi-emergency’ operation to stick one end of a plastic tube into his brain and rout the other end under his skin to shunt cerebrospinal fluid into his stomach, I was at the laundromat that’s right next to the Martha’s Vineyard airport. I was wearing a Hamilton College sweatshirt.

I think this was during that summer that we lost our rental and the five of us were camping out in a tent in the back yard of our friend Pam’s house, but I’m not sure.

Anyway a guy comes up to me, looks about 40, fit, nicely dressed, introduces himself as a Hamilton alum. A summer person, naturally. Turns out he’s a lawyer, on vacation. I’m not sure how an obviously wealthy guy like him ended up doing his laundry with us poor folk, but whatever. Somehow I find myself relating to him the story of the high-powered Boston lawyers that Betty & I had engaged to explore whether they would represent us in a malpractice suit. There was lots of actual malpractice during Jakob’s first two years — including before he was born — but the lawyers had concluded that under the law the only doctor against whom we had a chance of winning a case was a certain pediatric ophthalmologist — and he was one of the few doctors we liked, one of the very few who had listened to us and tried to help. We couldn’t see ruining the guy’s life — and of course there was no guarantee we’d win. So we decided to not pursue it. I finished my tale.

That’s when the Hamilton College lawyer’s eyes light up. “You’ve got a rock solid case to sue for loss of consortium!” he says. “Loss of consortium?” I say. “What’s that?”

“They deprived you of the son you could have had if they had detected and properly treated him.”

Now, Betty and I had spent more than a year working with those Boston lawyers. It took a lot of our time and attention working with those people, time away from our three children, going over our notes and medical records, recounting incidents over and over, reliving those painful, scary early years.

Loss of consortium can give rise to a personal injury claim. But unlike most personal injury cases, the person to be compensated is not the victim who was physically harmed or killed. Instead, close family members such as a spouse can bring this type of case because it is specifically intended to compensate for a lost relationship.

“The harm was not to me,” I say. “The harm was to my son. I’m perfectly happy with the companionship I share with him. Am I to go on a witness stand and perjure myself and say that my son, as he is, is some kind of tort, that I was gypped?”

But the lawyer in the laundromat persisted, “You could get a lot of money!”

“Spend another two years going over all those records, all those painful memories?”

“It could be a gold mine!”

I finished sorting and folding the clothes and left.

A good question

The problem I face in writing about all the adventures Jake and I (and Betty, and Jake’s two sisters too) have had as a consequence of his pre-natal infection by a cat-incubated parasite is that in conveying the drama — and there has been plenty of drama, some great stories, even — it’s not so much that I feel like I’m trading on his misfortune, it’s that the person of Jakob gets reduced to the background, and I don’t think that’s fair to him. In The Exorcist we learn a lot about Fr. Merrin and Fr. Karras and Regan’s mother Chris, and Detective Kinderman, among others — and more than we might like to know about Pazuzu — but very little about poor Regan herself.

Nearly 7 years ago I caught up with Jake in an emergency room bay at Brigham & Women’s hospital in Boston. The ambulance had gotten him there a half-hour ahead of me and I found him with his arms full of IVs, with EKG leads plastered all over him, and surrounded by a bevy of worried looking medicos. There were one or two people there from neurology, and somebody from infectious diseases, and one from psychiatry, maybe, and orthopedics. . . They had pulled in the big guns.

The paralysis seemed to be creeping up Jakob’s body. One or another doctor would poke him with a needle to ask him if he could feel it. At the place on his torso where he first could feel the pin they drew a line with a marker. The line had moved two inches closer to his neck in the twenty minutes he’d been there. I introduced myself as Jakob’s father & medical proxy and gave the assembled group a capsule history of Jakob’s rather long and intricate medical history.

Then I got the attention of the person who seemed to be running things and asked if he could give me a quick summary of where things stood. We stepped to a quiet place in the hall. “It could be from something poisonous, or an infection, or a neurological condition like Guillain–Barré syndrome, or a broken spine. . . We’re running a lot of tests. It may take a while to figure out what’s going on.”

We stepped back in to the bay, and Jakob spoke up.

“Would you say,” he enquired, addressing the doctors and nurses bending over him, their faces showing puzzlement and concern, “That this is more like an episode of House, MD, or more like one of Mystery Diagnosis?”

One thing you gotta know about Jakob: he’s a funny guy, and nothing freaks him out.

This essays continues in Toxoplasmosis, my Pazuzu, part 2.

Before recently losing the ability to read at all, Jakob read in what he called ‘face-book style’: with his nose nearly touching the page he’s reading.

Get well soon, Jakob, and go back to your books and to your wonderful, loving parents. As for the lawyer in the laundromat, what is wrong with people like that?