Sundman figures it out! is an autobiographical meditation, in the spirit of Michel de Montaigne, of a 71 72 year old guy who lives with his wife in a falling-down house on a dirt road on Martha’s Vineyard that dead-ends into a nature preserve.

Incidents, preoccupations, themes and hobbyhorses appear, fade, reappear and ramify at irregular intervals. If you like this essay I suggest checking out a few from the archives. These things are all interconnected.

Introduction

About two years ago my friend David Temkin told me that he was thinking of creating a new, third, issue of In Formation magazine, and asked if I might be willing to contribute something. In Formation #1 was published in 1998, and In Formation #2, Special Apocalypse Issue, was published in the year 2000. I am a big fan of both of those magazines. Riving In Formation after a twenty-five year hiatus? Cool! Sounds almost like something out of an SF movie! I jumped at the opportunity.

In Formation is and has always been a labor of love. Temkin (with the help of his friend Alex Lash, In Formation’s managing editor) enlists a group of writers, editors, graphic designers and the like, who all agree to work on the project without pay, just for the fun of it — and also because we believe in In Formation’s mission.

I suggested, and Temkin & Lash agreed, that I would write an essay along the lines of the Harvard Philosopher William James’ landmark volume The Varieties of Religious Experience. My essay would be called The Varieties of Silicon Valley religious experience.

I finished the draft more than a year ago, but producing a magazine with the incredibly high aspirations of In Formation #3, especially when nobody’s getting paid, takes a while. The magazine was finally published in the first week in July, and boy, was it ever worth the wait. I wrote about this project in my previous essay Silicon Valley über alles, and I really hope you’ll read that essay too, either before or after you read this one.

From the conclusion to that essay:

[I]f you have any interest in Silicon Valley ‘tech’ culture — what it is, how it evolved, how it has overtaken the world since the year 2000, the power it wields, the threat it poses — you owe it to yourself to obtain and read a copy of In Formation #3, a truly wondrous magazine — satirical, laugh out loud funny, and 100% serious and profound — two years in the making, written & produced by workers with combined centuries of experience in the belly of the beast; a print magazine wondrously designed, lavishly illustrated, exquisitely produced, published just a few days ago.

The article that follows is the text as it appears in the print magazine. I wrote the essay. Somebody else, Alex Lash, presumably, wrote the teaser intro.

The Varieties of Silicon Valley Religious Experience

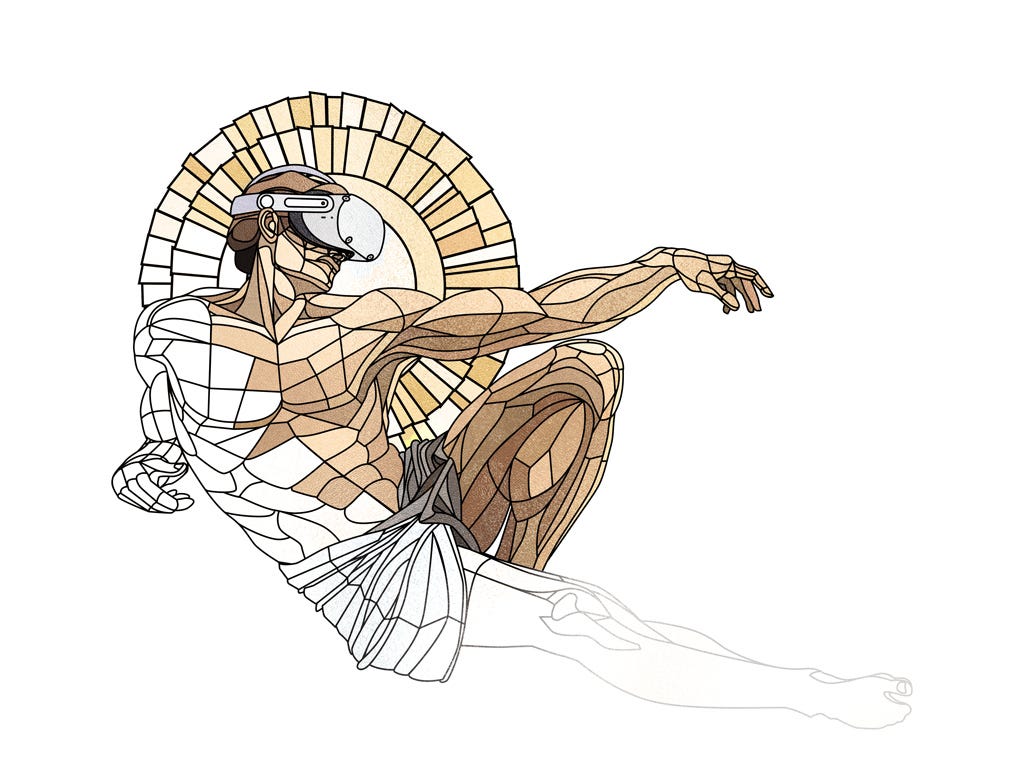

In the land of innovation, tech promises transcendence. The cults of crypto, biohacking, and life extension are updated gospels for the digital age – and one hell of a hustle.

By John Sundman

I spent the summer of 1971, when I was 19 years old, working in a spare parts warehouse near Place d’Italie, in Paris.

Staying in a hostel where most of my companions were immigrants, riding the Metro to work six days each week, doing a mundane job with everyday people was an eye-opening experience — and a great way to put my schoolbook French to use — though it didn’t provide much opportunity for either sightseeing or making deep connections.

But one evening, while walking in a Parisian neighborhood as the sun was setting, I encountered a pretty woman who looked about 25, handing out flyers to passersby. The flyers were long and narrow, like a receipt from CVS, with a question printed in red across the top, and at the bottom, also printed in red, a kind of logo and information about the time and place of a meeting. The question in red was Pourquoi la solitude de l’homme? That is: Why must people be lonely?

The gist of the message below those words was that while most people lived their lives in quiet desperation, not knowing how to find meaning for their existence and only rarely knowing real peace of mind, they didn’t have to live that way. There was another way, a life of radiant joy, open to all.

The woman invited me to a meeting which was just about to start to learn more about this radiant path. I was tempted. But I simply thanked her for the flyer, and, when I got back to my room, stuck it in my diary. It wasn’t until I returned to the States a month later that I realized that the woman was a member of the Unification Church — which was founded and led by a charismatic Korean preacher named Sun Myung Moon.

I like to think that I’m not the kind of person who would join a movement accused by young members’ families of being a cult. I’m rational, skeptical, and scientifically minded. But who knows what might have happened if I had gone, on a whim, to that meeting in Paris?

Well, the denizens of Silicon Valley also like to think of themselves as scientifically minded rational skeptics. Yet their corner of Northern California sits within a febrile crescent of America’s best-known crazes, faddish religions, and charismatic movements, from the 1849 Gold Rush to hippie communalism to the tragically messianic Jim Jones’ Peoples Temple.

Could it be that in the world capital of clear-headed innovation, spiritual seductions are actually central to the culture? Consider that the aspirational, tech-related philosophies associated with the Valley include fervent belief in a kind of liberation theology built around blockchain and “crypto”; Effective Altruism; and what might be called “biodigital utopianism,” a grab-bag that includes things like life-extension and extropianism, biohacking, and transhumanism.

That is: In Silicon Valley, are cult-like con games and pseudo-religious schemes the unavoidable outcomes of its inhabitants’ globally famous and relentless drive towards a better tomorrow?

The Valley and its beliefs

As an undergraduate I studied literature and anthropology, and in graduate school, West African farming systems. But somehow I became a “tech” guy, and over four decades held positions from the smallest of startups to the biggest players, from San Francisco to Cupertino, including Senior Manager of Engineering at Sun Microsystems — then, in 1992, the darling of Silicon Valley.

I always felt a bit like a fish out of water in this place where technology and worldviews are so entangled, and where people thought of religion as something passé, where “spiritual" talk was never heard. But it wasn’t the absence of religious feeling that disoriented me, it was the absence of any sense of history. Yesterday was gone, not even an afterthought. Everything was now, now, now — if not tomorrow, tomorrow, tomorrow. I’m a New Englander. We’re not like that.

Where I live, on Martha’s Vineyard, the island off Cape Cod, memories are long. A huge prayer shed built in the 1880s to host revivalist meetings still stands. Known as The Tabernacle, today it holds concerts and the annual high school graduation. Unlike Silicon Valley, we are comfortable living our history.

Yet as fast-moving as California is, in the 1960s and 1970s it was also home to its own kind of religious revival movements: the 1967 “Summer of Love” in the Haight-Ashbury; the repurposing of various flavors of Buddhism, Hinduism, and Native American spiritualism; “better living through chemicals” (psychedelics like LSD, mescaline, and “magic mushrooms”); and “back to the land” communal living.

By the mid-70s the hippie impetus had traveled south from San Francisco to give birth to the Human Potential Movement (HPM) at the Esalen Institute in Big Sur. Much as early Christianity mutated into diverse sects, HPM eventually encompassed phenomena as distinct as Erhard Seminars Training (known as EST – like Marine Corps boot camp, but for hippies), Jesus Freaks, and the Prosperity Gospel (20th century Calvinism, in which material wealth is a sign of being chosen by God).

The Esalen Institute also helped spawn Neuro-linguistic Programming (NLP), a pseudoscience created in the mid-1970s at the nearby University of California Santa Cruz. NLP’s developers essentially reverse-engineered common methods of human manipulation and sold their observations as how-to lessons for aspiring pick-up artists and salesmen, cloaked in lingo about the brain. In retrospect, rational tech and magical teachings were already cross-pollinating.

Take a look at a map of Northern California. The road from Haight-Ashbury to those communes in the Santa Cruz mountains and on to Esalen at Big Sur runs right up the middle of Silicon Valley. The same New Thoughts that animated those places were certainly in the air when Fairchild Semiconductor set up shop in Mountain View and Palo Alto, where the first practical silicon-based integrated circuit was invented – the unofficial birthday of Silicon Valley itself. But you’ll never hear today’s Valley evangelists acknowledge that spiritual legacy.

Hints of a new religious awakening?

Nearly 50 years after my encounter with the leafleteer in Paris, I had a strong experience of deja vu.

In November 2018, I found myself at the SynbioBeta synthetic biology conference in San Francisco listening to the millionaire technologist, investor, and biohacker Bryan Johnson’s keynote address. Like that beautiful young adherent of Rev. Moon, Johnson was promising a life of radiant joy. Johnson’s path involved a new and rapidly evolving kind of biodigital technology where the line between silicon-based digital technology and carbon-based analog technology (aka “people”) was growing ever fainter and would soon, he said, disappear entirely.

“My objective is to enable the tools that allow us to peer into our minds and see the inner workings,” Johnson said. “If we have that data available to us, an entire ecosystem can emerge, and we can start nudging our cognition.”

He talked about his daily regimes of exercise, diet (fasting and more than 100 supplements a day), and the meditative exercises he did every morning to “cleanse [his] mind of 18 cognitive biases.” Johnson had a Blueprint for Humanity, he said; he was at the vanguard of a “neobiological revolution” that would reverse aging, and someday, perhaps — just as Sun Myung Jesus Christ Moon claimed to do — show us the way to eternal life.

At the conclusion of his address, Johnson stood smiling beatifically as the audience applauded enthusiastically. The sense that we were all on the cusp of a brighter, technologically-driven future was palpable. It felt like a revival meeting.

In the fall of 2023, the venture capitalist Marc Andreesen published a silly little document called The Techno-Optimist Manifesto. It’s basically a libertarian rant about the virtues of technology, broadly defined, and about the evils of any effort to put restraints on either technology or markets. It includes a section on enemies, and a list of saints, and a list of beliefs in sentences that each begin with the words “we believe” — an echo of the Apostle’s Creed. (Credo in Deum, Patrem omnipotentem — I believe in God, the Father almighty.)

For example: “We believe markets, to quote Nicholas Stern, are how we take care of people we don’t know.”

The manifesto reads like something a 15-year-old might have written after reading Atlas Shrugged for the first time. I was struck by the absence of signatories; it’s as if the Declaration of Independence had been signed only by Thomas Jefferson. But because Marc Andreesen is who he is — a legendarily wealthy Silicon Valley engineer, entrepreneur and investor — his manifesto got a lot of attention.

Lightweight and commonplace as it might be, Andreesen’s Manifesto seemed to get under people’s skin, and a new category of essay came into being: the Anti-Andreesen Manifesto. Andreesen’s critics often pointed out that his techno-optimism had religious overtones, and that followings of personalities like Elon Musk had a cult-like feel to them.

An anti-Andreesen essay by well-known techno skeptic Paris Marx is typical. It’s called “The Religion of Techno-Optimism.” The subhead is “Tech billionaires are using faith to solidify their power.”

The notion of a religion of technology – whose Mecca is Silicon Valley – has finally emerged into the public consciousness.

From cult to religion

Whenever this topic comes up, I feel compelled to point out that in 1999 I published my novel Acts of the Apostles, which is about a religion of technology centered around a messianic evil genius Silicon Valley billionaire/technologist. The original New Testament “Acts of the Apostles” tells how, after the crucifixion of Jesus, his followers went about spreading the “good news” known today as Christianity.

Is it fair or accurate to talk about any Silicon Valley aspirational philosophy as a religion? Or a cult? Every belief system with adherents has to start somewhere. And the ingredients can come in varied proportions.

“Religion” is generally taken to involve matters that are supernatural or transcendental, that have organized rituals and ethical frameworks. Many religions, such as the Catholicism in which I was brought up, provide a way to deal with our innate fear of death.

“Cult” is used to describe a relatively small group led by a charismatic leader who tightly controls its members, with a strong tendency to enforce a separation between members of the cult and everybody else. Being in a cult is an all-consuming proposition.

One more point: religions and cults are often populated with leaders who profess quasi-magical abilities and credulous followers who take direction from them. This of course opens the door to con artists and malevolent narcissists who manipulate and prey upon unquestioning believers.

Keeping these observations in mind, let’s take a partial inventory of what Silicon Valley has to offer:

Techno-Optimism

The Techno-Optimist Manifesto asserts “Techno-Optimism is a material philosophy, not a political philosophy.” According to Andreesen, it does not concern itself with things that are supernatural or transcendental. It does offer an ethical framework of sorts, but it doesn’t address deep existential questions, and it doesn’t have much in the way of churches or rabbinical tradition, nor does it explicitly concern itself with transcending death. Techno-Optimism has none of the trappings of a cult (no charismatic authoritarian leader or enforced separation of adherents from humanity). It’s more a generally libertarian philosophy of technology that’s sometimes described by its adherents in quasi-religious language.

Crypto

Let’s say we roll up technologies involving blockchains, cryptocurrency, decentralized finance, smart contracts, NFTs and the like into a great big wad of stuff and label it ‘crypto.’ Are we in cult territory yet? Yes, I think so. There are significant pockets of crypto true-believers who think and act like people in a cult — with their own in-group lingo (WAGMI, HODL, diamond eyes), belief in magical crypto powers, and even a few efforts to form communal living enclaves centered around “the crypto lifestyle.” (See the 20-minute animated recruiting video called “Cryptoland” about an actual plan to build a crypto-centric utopia on an island in the South Pacific.)

Crypto cultism doesn’t offer a coherent ethical framework or a vision of an afterlife or any of the standbys of religious belief. But you have only to read accounts of the people taken in by the likes of Sam Bankman-Fried or Alex Mashinsky (of Celsius) to see people caught in the grips of delusion.

Effective Altruism

To understand the movement known as Effective Altruism, or EA, imagine a kind of smug stepchild of the Prosperity Gospel and Ayn Rand gussied up in the language of utilitarian philosophy. Its adherents celebrate “using evidence and reason to figure out how to benefit others as much as possible, and taking action on that basis.” Unlike Techno-Optimism or libertarian-inflected crypto fetishism, EA does purport to offer an ethical framework for deciding right from wrong and for helping you know what to do with your life. But it has nothing to say about anything spiritual or transcendental. It’s kind of post-all-that.

Biodigital Utopianism

If there is one common theme that pervades most of the quasi-religious movements coming out of greater Silicon Valley, it is a belief that personal technologies are destined to enhance individual human minds and bodies. In other words, the belief is not just that technological solutions will be found for the climate crisis and that markets will become ever more efficient at producing ever-greater quantities of ever-greater goods, that AI will replace drudgery and so on. Rather, biodigital utopianism holds that technology will change the very nature of the human being – lives become ever longer and healthier, and minds become more powerful. The meat substrates you and I now find ourselves embodied in will gradually be supplanted by newer, superior forms not yet devised.

In his trilogy of fantasy novels His Dark Materials, Philip Pullman creates an alternate universe in which the Age of Enlightenment proceeds a bit differently than it did in ours. In Pullman’s universe, science and theology were always one “experimental theology.” In Silicon Valley, experimental theology takes various biodigital utopian forms, including life extension, extropianism, biohacking, and transhumanism.

Biohacked eucharist

One year before Bryan Johnson’s Synbiobeta keynote address, I attended another event hosted by the company in which self-described biohacker Josiah Zayner injected himself with a CRISPR cocktail of enzymes, RNA, and DNA to edit the DNA of his own muscle cells. This “workshop” was definitely a sideshow, not a focal event of the Synbiobeta conference. There were only about twenty-five of us at the low-key affair. I was about ten feet away from him.

Between the distribution of the sacramental beverage and the ceremonial preparation of the transformative substance to be ingested by the celebrant, there was almost something of the Catholic mass about Zayner’s performance. It reminded me of the consecration of the eucharist.

Although it was more of a stunt than a serious attempt at Do It Yourself genetic engineering, Zayner's ostensible self-edit did make waves, and was widely discussed in the biohacking, transhumanist, and hacker online communities. Stunt though it may have been, the Zayner CRISPR demonstration marked a Rubicon of sorts, the edge of a black hole, a point of no going back. Genetic editing is undeniably out of the lab, in the wild. Elsewhere we see reports of famous Silicon Valley tech/spiritual leaders literally transfusing the blood of virgins into their veins, ingesting placenta, exploring any and every “modern, scientific” road to the Fountain of Eternal Youth.

So yes, biohacking is here to stay. With it will come, I feel confident in predicting, all manner of new flavors of biofuturism: Frozen-head Cryonicism, Pan-human Biodigital Extropianism, People’s Front for the Liberation of Consciousness, and Conscious People for the Front of Liberation. The practitioners aren’t even shy about saying their ideas are religions, like that pronatalist family, the Collinses, with big eyeglass frames and viral articles about their baby-creation methods. They call their religion “secular Calvinism.” Who needs God when you can be God – but smarter, right?

Making immortals

Is the religion of Silicon Valley something new, or just a repackaging of something we already know?

Looking back to the cultural currents in the air in the 1960s, when South Bay orchards and fields were giving way to foundries etching the first integrated circuits into silicon wafers, we can see the progression from the Protestant ethos of the information-age pioneers to the “human potential movement” of Silicon Valley today.

When I first arrived in Silicon Valley there was a zealotry about the place, distinct from the religious grounding of Martha’s Vineyard. Had the Valley’s absence of history made it susceptible to new cultish ideas about the amazing paradise on Earth to come? Pol Pot’s “Year Zero” in Cambodia required that the past be obliterated. It's easier when there is no past.

Today, the Valley’s true believers have been drawn to beliefs that sanctify their chosen profession and goals, and provide a teleological framework that substitutes for old-school religion that – for the scientific set – would otherwise be a source of embarrassment. And they’re drawn, as humans have always been, to the potential for immortality.

Current tech-driven obsessions with life extension are mere substitutes for the Christian concept of eternal life: transfiguration of humans into gods through biotech and self-modification — and of course getting rich from all of these activities, while… doing good!

The fear of death is deeply embedded in the people who pursue these techno- and bio-utopian dreams with the utmost fervor, leading to a sort of substitute religion with, perhaps not incidentally, its charlatans.

And let’s face it, there’s money to be made ridding people of the fear of death.

At the 2018 SynbioBeta conference, Bryan Johnson talked about raising tens of millions of dollars or more to launch a worldwide movement to transcend the limitations of the default human bodies we’re currently inhabiting. What’s he up to these days? According to Business Insider, as of January 2024, “Millionaire Bryan Johnson is making his anti-aging 'basics' available for $333 a month to 2,500 people.”

Let the spirit guide you. Even Jesus started small.

Author bio:

Since 1980 John Sundman has worked for nearly two dozen software and hardware startups in Silicon Valley, San Francisco, Boston, and NYC. He has also been a firefighter and a long-haul truck driver. His cyberpunkish novels include Acts of the Apostles, Cheap Complex Devices, Biodigital, and The Pains.

Passing the collection plate

I’m just a poor writer who’s trying, and not always succeeding, to make enough dough to pay his mortgage & car payments on time. (My situation is actually pretty scary right now.) If you enjoy my kind of writing and would like to help out, please consider upgrading to a paid subscription. If you’d just like to make a one time-contribution, here’s a link to buy me a coffee (any amount welcome — pay no attention to the exorbitant suggestions).

I’m now offering ‘merch’ at my ‘Buy me a coffee’ page. The first item on offer: In Formation #3.

Cheerio!

John, thanks for this post, my comment on the last post was a bit premature. The "cryogenic" era of life-extensionism certainly was fun, people would hand out laminated cards to (some) of their friends with a phone number to be called in the event of their death. Since most had yet to make their big score, all they could afford (for a big up front fee and a monthly "maintenance" fee) was to get their heads frozen. So, those of us who were unenlightened called them the "freezer heads". I assume there are still some freezers running somewhere in Marin with a few remaining occupants.

There is there was that weird set of followers of the "teachings" of Aleister Crowley, a convoluted thread that passed through L. Ron Hubbard, Robert Heinlein, Jack Parsons, JPL, Caltech, and from there into the early SF/SV engineering scene. And, of course the biggest SV cult of all, the followers of the Gospel of Saint Ayn Rand.

There are, I believe, a few things that may be hard to see except from an outsider (non-white) perspective. The first is the relentless "whiteness" of the proposed techno-utopias, at least until a PR person notices and darkens in a few faces. I don't think this is accidental, nor is it accidental that William Shockley was one of the founding "fathers" of Silicon Valley and a true believer in eugenics his entire life. Now let's move jump to Elon Musk and all those baby mommas, each required to take a genetic test before they could join the fun. Just what sort of genetic "impurities" would he be looking for? Looked at another way, we have white "engineers" engineering a white future, the one true religion of SV. How many non-white people were allowed into Galt's Gulch?

Amen.

See David Noble The Religion of Technology and A World Without Women (Knopf).

My The View From Asilomar is on my Substack On Watch. Later this summer I will post a short essay on AI and San Francisco.

The political meaning thereof. See Gil Duran (Nerd Reich) at the Commonwealth Club.

Excellent essay. Kudos.