Sundman figures it out! is an autobiographical meditation, in the spirit of Michel de Montaigne, of a 71 72 year old guy who lives with his wife in a falling-down house on a dirt road on Martha’s Vineyard that dead-ends into a nature preserve.

Incidents, preoccupations, themes and hobbyhorses appear, fade, reappear and ramify at irregular intervals. If you like this essay I suggest checking out a few from the archives. These things are all interconnected.

Précis

Three days ago I watched a video of a two-hour long presentation about the evolution of the culture of Silicon Valley (and by extension, of the world of ‘tech’), over the forty five years from 1980 until now.

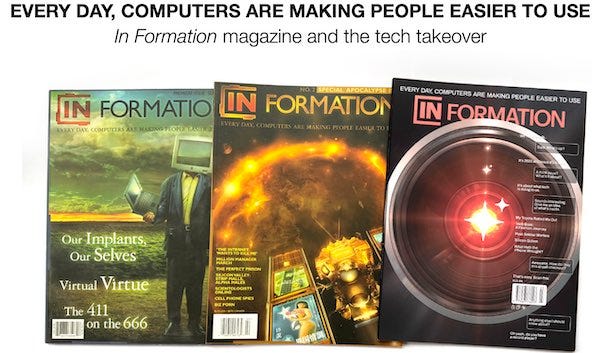

The occasion of the talk was the publication, after a twenty-five year hiatus, of the third issue of In Formation magazine, whose focus is ‘what tech is doing to us,’ and whose tag line is “Every day, computers are making people easier to use.”

My essay ‘The Varieties of Silicon Valley Religious Experience’ appears in In Formation #3.

The presentation, by In Formation’s founder and editor in chief David Temkin and contributing editor Paulina Borsook, a prominent observer and critic of Silicon Valley culture, was given to a private group, and, alas, I’m not at liberty to share the video.1 But I’ve been given permission to share some of the slides.

The period of Silicon Valley culture covered by Temkin & Borsook’s presentation, 1980 to 2025, precisely overlaps my own involvement in the land of tech, and as I listened to them I felt almost as if I were on some kind of DisneyWorld ride getting a tour of my own evolution from untutored tech neophyte to jaded technoparanoid greybeard.

This post, then, weaves three strands: the cultural evolution of logical Silicon Valley; what that evolution looked like and felt like to me as I lived through it; and the three remarkable instantiations of In Formation magazine, particularly the astounding issue #3, which was just published on July 1, 2025.

By the time you finish reading this essay, if I’ve done my job well, you’ll be dying to get your hands on a copy of that remarkable document — a work of art, really — called In Formation #3. At the conclusion of this post I tell you a couple of ways you can do that

A note on bicoastalism and Silicon Valley synecdoche

With the exception of the twelve months from summer, 1993, through summer, 1994, when my family & I resided in Fremont, in the ‘East Bay’ region of greater Silicon Valley, I have resided in Massachusetts from January 1980 until now. However, over the course of the 9 years I worked at Sun Microsystems starting in January, 1986, the 5 years I worked at Laszlo Systems, and consulting gigs of various durations at a dozen or so San Francisco or Silicon Valley startups, I’ve made at least 130 round trip flights between Boston’s Logan Airport and SFO or San Jose. I’ve spent at least one night in every hotel on El Camino Real between Burlingame and Santa Clara, not to mention a bunch in San Francisco. I know that area well.

Wikipedia:

Synecdoche is a rhetorical trope and a kind of metonymy—a figure of speech using a term to denote one thing to refer to a related thing.

Wikipedia:

As more high-tech companies were established across San Jose and the Santa Clara Valley, and then north towards the Bay Area's two other major cities, San Francisco and Oakland, the term "Silicon Valley" came to have two definitions: a narrower geographic one, referring to Santa Clara County and southeastern San Mateo County, and a metonymical definition referring to high-tech businesses in the entire Bay Area. The term Silicon Valley is often used as a synecdoche for the American high-technology economic sector.

There is a common culture among people who work who work in the U.S. high-tech sector. Sometimes the term ‘Silicon Valley’ is used to refer to this sector broadly. I try not to do that. I try to use the term ‘tech’. But it gets messy. Sometimes you may have use context to figure out what meaning of ‘Silicon Valley’ is intended.

A couple of intersecting subsets of this broader Silicon Valley/tech culture particularly concern us here:

What might be called ‘systems’ culture, meaning engineering, particularly ‘systems engineering’: people who design computer systems and write code that runs ‘close to the metal’. Usually such people have formal training in computer science, but Tom West (see below) had little, and I had none;

people who live or work in the high tech sector within the actual geographical boundaries of Silicon Valley.

One theme that has appeared in my writing, especially my novels, is the disjunction between tech culture in Massachusetts (heavily influenced by MIT, and perhaps by puritanism), and tech culture in Silicon Valley (Stanford, hedonism).

On the other hand, In Formation magazine’s focus is the evolution of the culture of geographic Silicon Valley — from the ‘systems’ culture of its early days to whatever the fuck it is now.

Tom West, the original geek rock star, welcomes me to his world

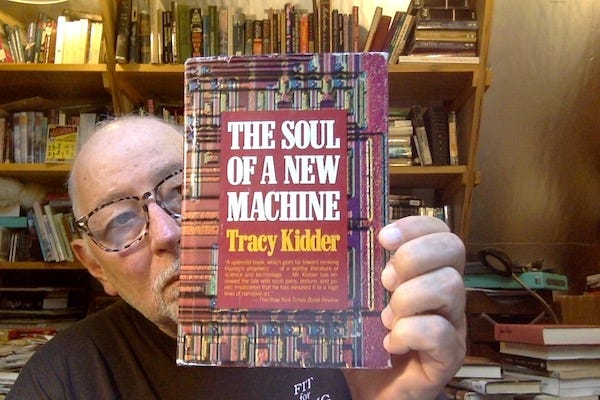

You of course remember Data General, where I had my first tech job, from Tracy Kidder’s epic Pulitzer Prize-winning The Soul of A New Machine, forty-four years old and still the greatest non-fiction book yet written about the thrill of designing a computer’s central processing unit, the CPU. Tom West, the Ur-geek rock star, is the central figure in Soul of a New Machine. He personified the culture of systems engineering.

Tom West, with whom I worked at Data General, is the ‘Tom’ alluded to in my essay What’s the frequency, Tom? which also discusses New Age mystical woo-woo, and my first ever, and quite eerie, trip to California: as I drove a rented car through heavy fog at 2 AM from SFO to Mountain View, a song came on the radio: These Dreams, by Heart. It was kismet.

When finally got to my hotel room and turned on the television, every channel was showing videos of the explosion of Space Shuttle Challenger.

When Tom passed away in 2011, the obituary on the front page of the Boston Globe included these words:

Thirty years ago, Tom West was thrust into a category of one, a famous computer engineer, with the publication of The Soul of a New Machine.

Tracy Kidder’s book, which was awarded the Pulitzer Prize and is [still] taught in business classes and journalism schools, chronicled Mr. West’s role leading a team that built a refined version of a 32-bit minicomputer at a key juncture for the computer industry and his employer, Data General of Westborough.

The book’s success turned a quirky, brilliant, private, and largely self-taught man into a somewhat reluctant guru.

Now, if you weren’t around in the early 1980’s, you might be thinking, How could Tom West be a ‘category of one, a famous computer engineer’? Wasn’t Steve Jobs, the computer engineer and co-founder of Apple Computer, already famous by then?

The answer is yes and no. In 1981, Apple was only 5 years old, and the MacIntosh was four years in the future. Steve Jobs was getting pretty famous by 1981 but he was still mostly known within the tech universe. Soul of a New Machine, on the other hand, introduced Tom West to the general public. More importantly for our current discussion, Steve Jobs wasn’t really an engineer. He was, rather, a world-class hustler. As his fame grew, it was for his talents as a visionary entrepreneur, not as an engineer.

Tom West was a pure engineer, and my welcome to his world was like a plunge into deep cold waters of bits and bytes and semiconductor substrates and assembly language programming.

With Steve Jobs, however, we begin to see the transformation that In Formation analyzes. Already slick California showmen like Steve Jobs were starting to steal the limelight from Massachusetts geeks like Tom West.

The note in the upper corner says,

From lab coats and polyester to that-grey-vest, the rise of the tech bro tracks decades of shifts in style — and in substance. We trace the arc of the Silicon Valley male look from the days of nerdy, unassuming scientists to vain, barely technical megalomaniacs chasing immortality.

Paulina Borsook, my apostatic doppelgänger

I mentioned a video of a presentation by David Temkin and Paulina Borsook.

I’ve known David since 2003, when he hired me to be the sole technical writer at Laszlo Systems, the second of the three San Francisco/Silicon Valley startups he’s founded. I worked quite happily at Laszlo for nearly five years, until David fired me on my 55th birthday in late November, 2017 in order to kick off the Great Recession of 2008, in fulfillment of the scriptures. I’ve only met Paulina quite recently, but in some ways it feels like we’re old friends.

From Wikipedia, again:

Paulina Borsook is an American technology journalist and writer who has written for Wired, Mother Jones, and Suck.com. She is perhaps best known for her 2000 book Cyberselfish, a critique of the libertarian mindset of the digital technology community.

What Wikipedia doesn’t say is that she’s also really funny. See, for example, her Salon essay from 1999, How the Internet ruined San Francisco. She isn’t joking, but she is funny.

I’ve been vaguely aware of her book Cyberselfish since it came out in the year 2000 —within a month or two of my first novel Acts of the Apostles, a nano-bio-cyberpunk thriller about a Silicon Valley evil genius and would-be messiah and the cult of techbros who venerated him. Even before I read Borsook’s book Cyberselfish I knew from its title and synopsis that its author & I were on the same page.

Like my novel Acts of the Apostles, Borsook’s Cyberselfish (which is having a reputational renaissance and really needs to come back into print), was a pioneering rejection of many of Silicon Valley’s core philosophical principles. In fact, in listening to her comments a few days ago about the mindset, geography, architecture, and culture of Silicon Valley in the 1990’s, I kept on thinking of passages in my novel that talked the same things.

According to Paulina, her reward for blazing the trail was financial ruin and the end of her journalistic career.

A decade or so after the appearance of Cyberselfish, other ‘contrarian’ writers made big names for themselves writing things strangely similar to what Paula Borsook had written ten years before them, for which she was seldom if ever given credit.

But out of nowhere, just a few months ago, a person she had never met created a website to resurrect her reputation and champion her cause. I hope you’ll take a look.

We can hope that she’s finally getting the recognition she deserves.

My career from logic gates & assembly code to AI & personal immortality mapped to three issues of In Formation

The first slide from that Borsook/Temkin In Formation presentation that I watched three days ago looked something like this:

In Formation: A magazine and the madness of the Valley

* Silicon Valley in the before-times: 1980 - 1995

* The dot-com boom (and bust): 1995 - 2001

++ In Formation #1 (1998)

++ In Formation #2 (2000)

* The internet triumphs (2001 -2022)

* Humanity subordinated (2022 — )

++ In Formation #3 (2025)This chronology made me laugh for a couple of reasons. First, because my own career in ‘tech’ started when I got a job as a junior technical writer at the Massachusetts computer maker Data General in April, 1980, a job for which I was completely unqualified. By 1995 I had written about twenty hardware and software manuals and become a senior manager of engineering. Eventually, like so many others, I moved to Silicon Valley. But things happened, and my family and I fled the Valley for the island of Martha’s Vineyard in late 1994, just at the start of the world wide web. I avoided tech altogether for the next six years.

Thus my first stint in the world of tech mapped exactly to what Temkin & Borsook call ‘the [Silicon Valley] before-times’. Which is to say that from the perspective of the creators of the first issue of In Formation, my formative years in Silicon Valley might just as well have happened during the Pleistocene. I thought that was pretty funny.

The years that they call ‘The dot-com boom and bust’ map almost exactly to the years I spent out of tech, doing manual labor on Martha’s Vineyard and working on my first novel.

When I crawled back to tech in the spring of 2000, after six years away, and took a job as manager of information architecture at an MIT/Kendall Square startup, the dot-com bubble had come and gone. In the 22 years between the turn of the millennium and 2022, I had been a Schrödinger's geek, living and working in the logical Valley and not living and working there: going back & forth between jobs like operating a forklift on the graveyard shift in a refrigerated warehouse or crawling on my belly like a reptile under Carly Simon’s house to flying to San Francisco to consult with some new virtual reality or ‘big data’ startup. These are the years that Temkin and Borsook label ‘The Internet triumphs.”

Near the end of 2022 I quit what I dearly hope will be my last-ever tech job, as the sole writer on a cryptocurrency startup (as chronicled in my essay 100% Bafflegab.)

My preoccupation since then has been technopotheosis, or what Borsook and Temkin label ‘Humanity subordinated.’

Which is to say that in one simple slide, Temkin & Borsook showed me the outline of my entire post-Africa working life.

Humanity subordinated?

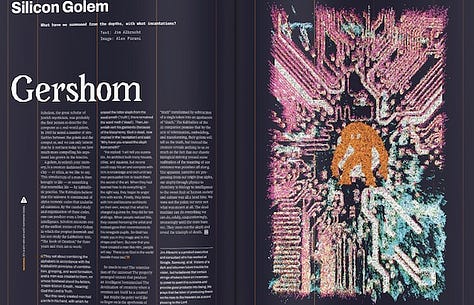

My contribution to In Formation #3, 'The Varieties of Silicon Valley Religious Experience,' an essay in the spirit of the philosopher William James's 1902 landmark tome The Varieties of Religious Experience, is an investigation of transhumanism, extropianism, life-extension, and related movements associated with Silicon Valley as religious 'revival' phenomena preoccupied with achieving transcendent wisdom & denying the finality of death.

That’s a long way from Tom West and the kind of soul of a new machine that Tracy Kidder was talking about.

In Formation #1 (1998) and In Formation #2: Special Apocalypse Issue (2000) in a nutshell

Since the odds are extremely high that, unless you happen to own either or both of Information #1 or #2, you’ll never actually see either of them, there’s no point in my discussing them in much detail. But I here make a few comments about the first two In Formations because I think it may help you understand where #3 is coming from.

Borsook & Temkin’s slide for the dot-com bubble years summarizes the key trends like this.

The Internet transforms the Valley

* Techno-utopianism arrives

* Techno-libertarianism arrives

* The money is suddenly flowing

* And a new kind of person migrates to Silicon Valley

All of this was just begging to be critiqued — and mockedSo it was that in 1998 David Temkin assembled a crew, including Paulina Borsook and twenty or so other passionate, demented and talented volunteers, and they created In Formation. And then two years later, they did it again, with In Formation #2, Special Apocalypse Issue.

I have copies of both issues. They contain lots of brilliant writing and some nice graphic design. There’s serious cultural critique and lots of satire — some of it subtle, others not so much. The interior pages are black and white.

So In Formation, numbers 1 & 2, give you an idea of the kind of topics you can expect to be addressed, and the approaches to be taken, in In Formation #3.

But they in no way prepare you for the experience, because In Formation #3 is vastly more ambitious than its predecessors in every respect: graphic design, range of voices, subtlety of approach, quality of production, seriousness of intent. . .

It’s as different from issues 1 and 2 as the Beatles’ A Day in the Life is from I want to hold your hand.

My back pages 1995 — 2025

If the story of 1995 to 2001 in tech was the emergence, absurd growth, and dramatic popping of the dot-com bubble, the so-called ‘New Economy,’ my story was a bit different. I witnessed those events from a perspective far away from Silicon Valley, yet oddly connected to it.

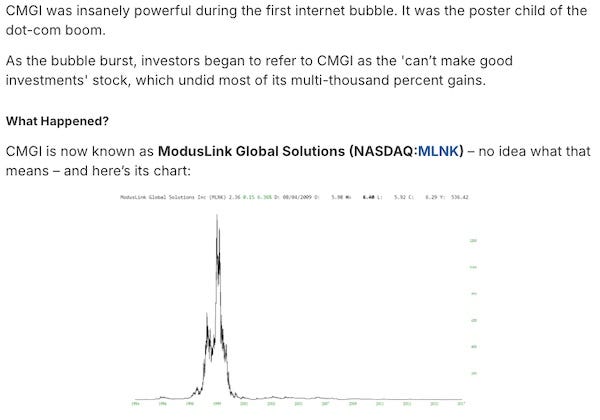

For the entire year of 1999, with the exception of those weeks that had me crawling on my belly like a reptile under Carly Simon’s house, I was a common laborer on the Martha’s Vineyard trophy house of CMGI mogul David Wetherell. For a very short time Wetherell was a New Economy billionaire, the darling of the business press, his face on the cover of Forbes and Fortune. Then the bubble burst and the price of a share of CMGI stock went from ~$250 to thirty-nine cents, and the stock was delisted from NASDAQ.

Very few people know that I, myself, John Sundman, was personally responsible for the implosion of the dot-com bubble — but if you want to know more about that you’ll have to read this essay I wrote for Salon in which I told the whole amazing tale:

Oct 23, 2002 How I destroyed the new economy Dot-com visionary David Wetherell could do no wrong — until he started building a mansion on an ancient Indian burial ground.

Sounds unbelievable, right? But I was there. I saw it happen. It was as if the Valley was following me to the ends of the Earth.

“I’m 70% scared by all this and 30% excited. What would you say your ratio is?”

In Formation #3: from the ashes to of the dot-com conflagration to technopotheosis

From the welcoming essay to In Formation #3, written by David Temkin and In Formation Managing Editor Alex Lash:

This isn’t a new publication. We published the previous issue 25 years ago, during the dot-com boom. The internet was just emerging from its academic cocoon and beginning to sink its teeth into society. The hype and absurdity were off the charts and we mocked it all relentlessly. But where the era’s promoters hoped to take us was no laughing matter: we saw the warning signs and took a wild swing at what their utopia could mean for all of us.

And here we are, a quarter of a century later.

We regret to inform you that we were right. The first wave of internet transformation did what it promised, or threatened to do — and more. We live in a world irrevocably changed by geeks and laptop-class douchebags from Silicon Valley, where douchebaggery and laptops are both state of the art.

What we’ve come to call ‘screen time’ now consumes the waking, and walking, hours of billions of people. Relationships, work, fun and everyday communications have been reformatted. The revolutionaries have become the establishment; the rebels the emperors; the charming little upstarts have calcified into monopolies. And speculation that sounded paranoid 25 years ago now sounds like a quaint relic of an innocent age.

In Formation is back, baby. Why? Because we’re at another inflection point. It’s no about ‘the internet’ this time. That ship has sailed. This tsunami is shaping up to be more radical, deeper, yet served up in a familiar way: bland promises of even more tech awesomeness, promoted with the same old Silicon Valley self-congratulatory patter, while insidiously threatening to alter the most fundamental elements of human life.

Below, some representative pages. But they give only the barest suggestion of what this thing looks, or feels like — or even smells like (a slick magazine!) or sounds like (the magazine includes a flexidisk analog record of two songs by ‘The Layoffs’ that you can play on any record player.)

As I wrote in my congratulatory note to David Temkin after FedEx dropped off a box of #3 at my door,

David, no matter what may come of In Formation #3 — and I hope, for you, $$$, and all kinds of doors opening — this is truly an achievement, an accomplishment, a work of art, a thing of beauty and an intellectual challenge to anybody who dares to read it. It is a no-kidding, fuck you, go to hell, bitch-bastard, holy shit, mother fucker of a magazine. It is not an entertainment. It is a serious, urgent, necessary challenge disguised as an entertainment. OhMyGawd. I'm blown away. I love it so much.

Many people helped — I'm proud of my small contribution — but In Formation #3 is, (borrowing a phrase from Spike Lee), a David Temkin joint. We helped, David, but you did this. It's your joint. Be proud.

I salute you. I tip my cap. I am honored that you invited me to participate and I thank you again for doing so. I am quite pleased that I can call you my friend.

So please, go to the In Formation website. Look at the illustrations. Check out the contents. Read about the contributors. And buy a copy.

What is your fear/excitement ratio?

A few more words from the In Formation #3 welcoming essay:

Maybe we are in fact headed for a world of infinite abundance, creativity, convenience and eternal life. No, really, it’s possible. Or maybe we’re headed for a world in which billions of people are warehoused in virtual reality coffins, being influenced by no one by influencers, and trolled by trolls who don’t exist, subsisting by renting out 50% of their neural capacity for AI processing.

We’re at a moment where previously philosophical questions have become entirely practical: What is real? What is human? Are we transitioning from individual beings to cells of a single global organism?

It sounds crazy mostly because it is crazy. But dismiss “crazy” at your own peril; recent history shows how quickly it becomes the new normal.

In the Q & A at the conclusion of Temkin & Borsook’s talk, an audience member said, “I’m 70% scared by all this and 30% excited. What would you say your ratio is?”

David Temkin replied, “Seventy-thirty sounds about right.”

Paulina Borsook said, “Ninety-ten.”

Myself, I’m about ninety-seven/three. And although I hate to say it, I have a very good track record.

What’s your ratio? Leave a number in the comments.

Every day, computers are making people easier to use.

If you want to know what it feels like to work ‘close to the machine,’ designing and building computers, getting system software to run on them (and it really is an awesome, addicting feeling), read Tracy Kidder’s The Soul of a New Machine, or Sundman’s Acts of the Apostles (or Biodigital) — or preferably all of them!

But if you have any interest in Silicon Valley ‘tech’ culture — what it is, how it evolved, how it has overtaken the world since the year 2000, the power it wields, the threat it poses — you owe it to yourself to obtain and read a copy of In Formation #3, a truly wondrous magazine — satirical, laugh out loud funny, and 100% serious and profound — two years in the making, written & produced by workers with combined centuries of experience in the belly of the beast; a print magazine wondrously designed, lavishly illustrated, exquisitely produced, published just a few days ago.

Here are three ways you can get your hands on a copy

Upgrade to a paid subscription of Sundman figures it out!;

Order a copy from me using my Buy me a coffee page;

Buy directly from the In Formation website.

P.S. If you’re a current or former paying subscriber to Sundman figures it out! and haven’t yet claimed your free copy, please send me a note. (USA only. If you’re outside of USA, send me a note & maybe we can work something out.)

Passing the collection plate

I’m just a poor writer who’s trying, and not always succeeding, to make enough dough to pay his mortgage & car payments on time. (My situation is actually pretty scary right now.) If you enjoy my kind of writing and would like to help out, please consider upgrading to a paid subscription. If you’d just like to make a one time-contribution, here’s a link to buy me a coffee (any amount welcome — pay no attention to the exorbitant suggestions).

I’m now offering ‘merch’ at my ‘Buy me a coffee’ page. The first item on offer: In Formation #3.

Cheerio!

It’s a shame that so few people saw this presentation. I hope that the private group can be persuaded to share it, or that David & Paulina can be persuaded to give the presentation again, this time in a public setting & with an unencumbered video recording.

Bought my copy last week.

On issues #1 & #2, would there be any objections to digitizing one of those physical copies and making them available as PDFs or something similar?

I’m officially switching my view of Seven Degrees of John Sundman from “whose else is he a first degree” to “who the hell isn’t?” Tom Fucking West?