Jerrycans full of gasoline in the back seat(2)

The most intense three hours of my life so far, part two of two parts

Preliminaries

Immediately after sending out part one of this essay I discovered a few typos. A ‘the’ should have been a ‘thee'; a ‘2003’ should have been a ‘1973’ and one ‘1973’ should have been a ‘1974.’ Sorry about that. These mistakes are fixed in the archival version of this essay, Jerrycans full of gasoline in the back seat(1) .

Part one concluded like this:

“John! John!” They said, gasping. “Everyone on the whole campus is looking for you. A doctor called from Utica. You have to get to the hospital absolutely as soon as you can.”

The unstated subtext: “If you want to say goodbye.”

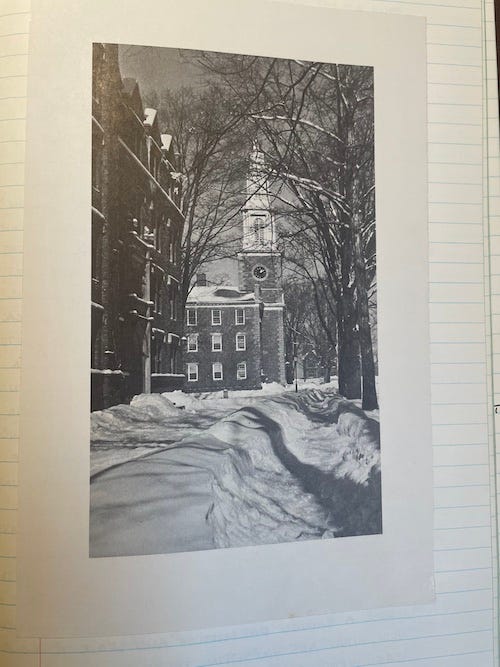

Snowfall in the Mohawk River Valley

Winters at Hamilton/Kirkland college were characterized by two things: cold and snow. It snowed all the time and you could hear little bobcat snowplows clearing paths between buildings from Halloween through Easter. There was a lot of snow on the ground on February 23, 1974.

The first carjacking

If I was going to get to the hospital in time for whatever awaited me there, I needed a car, right now. The person who had found me and delivered the message did not own one. I had friends who had cars, but how would I ever find them quickly enough?

A few yards away I saw a student walking, a guy I vaguely knew from somewhere, but certainly not a friend. I ran to him. “Do you own a car?” “Yes.” “Where is it? Give me the keys.”

There was probably a bit more to our conversation than that, but not much more. I was making a demand, not a request. I might even have threatened him. He gave me the keys. The car was not far away, in a parking lot behind Dunham Dorm. I sprinted to it.

Clarification of the meaning of ‘most intense’

When I wrote in the subhead to this post that this is a story about the ‘most intense three hours of my life so far’ I did not mean to imply that these three hours are the scariest, most emotional or consequential three hours of my life so far. The experience of getting jumped and knifed in a dark alley was pretty darn intense, for one small example, but that whole incident, from the struggle over the knife until when the police dropped me off only lasted about 30 minutes.

As parents Betty and I have had to navigate, jointly or individually, various tricky situations where the life of one or another of our three children was at stake, where if we hadn’t figured out exactly what we needed to do we would have lost them. Those situations were every bit as intense and consequential as anything discussed in this post.

But I say that this ‘jerrycans’ story is the ‘most intense 3 hours of my life so far’ because of the ridiculous cascade of improbabilities, like anvils falling out of the sky, that did not relent for three solid hours.

The only thing I can compare it to is wiping out in hurricane surf. You fall off your surfboard and get tossed all about as if you’re in some diabolic washing machine. Your head smashes into the sandy floor. You cannot tell which way is up and you are certain that you are going to drown. Just when your lungs are about to burst you pop to the surface and get a gulp or two of air, amazed that you’re not dead. You find the leash bound to your ankle and pull your surfboard to you. You are almost back on the board, which will maybe give you a chance of making it to the beach, when another wave, this one about a thousand feet high, crashes down upon you and you are back in the devil’s wash cycle once again.

The second carjacking

With the keychain in my hand and the car in sight I sprinted for all I was worth. I arrived at the car, went to unlock it. . . and discovered that somewhere between where I had commandeered the car keyes and the actual car itself the key had fallen off the chain. There was no time to return the useless keychain with the guy’s other keys on it; I just dropped it.

I looked all around me in the lot, there was nobody there. I was inexplicably all alone in Antartica.

But then I saw my friend Fred. I ran to him. Fred owned a car. He had the keys in his pocket. He showed me where the car was and started it for me. He got out and I got behind the wheel. Vroom.

At the hospital

I don’t remember driving to the hospital or how I made my way to where Anne was being prepped for surgery, but I did get there in time.

I found her in the center of a medical bustle like something out of a TV show. She had an oxygen tube up her nose, IVs in both arms delivering blood and saline, and all manner of blood-pressure cuffs and wires and God knows what-all. People wearing masks and gowns were doing things that needed to be done while I tried to not get in the way. I was there only long enough for me to see her, and for her to see that I had gotten there in time to see her off. Neither of us spoke.

As they wheeled Anne towards the operating room the surgeon, looking far too serious, came over to me:

“She has lost a lot of blood and is still hemorrhaging. I don’t know if we can stop it. It is very serious. Prepare yourself.”

Then he was gone.

I should prepare myself, the doctor said. Yeah, right. I thought. I’ll make a point to do that.

Impatience

The waiting room outside the operating room at St. Luke’s was about the size of the storage room in Bundy Dormitory that had been my home for the few weeks prior, and just as cheery. There were some other people in the room with me and a few magazines. But I was in no mood to visit with anybody or read any magazine. It was a thoroughly depressing place in which one might attempt to prepare oneself.

But there were reminders throughout the hospital that blood donations were always welcome, so I decided to see if I could donate a pint of blood.

However when the people at the blood bank checked their records and saw that I had made a donation three days earlier they practically threw me out on my ear. Although some part of me knew that I would not be eligible to make another donation for two months, I had gone there thinking that maybe some of my blood could be transfused to Anne.

I was not thinking clearly. I was borderline nuts.

New arrivals in the waiting room

When I got back to the waiting room there were two people who had not been there before: a tall handsome guy and a woman wearing green glasses. Dr. Harrison McAllister, a dentist from Delaware and his wife Annie — Anne’s father and mother. They had just driven nonstop from Wilmington, a distance of 300 miles.

In order to deal with the gas-rationing situation they had filled several five-gallon jerrycans with gasoline and put them in the trunk and back seat of their car. In order to deal with the noxious gasoline fumes, they drove the whole way with the back windows open. Back windows open in a car moving at highway speed in an upstate winter.

I don’t recall whether Anne’s parents knew at that time that Anne had a new boyfriend. I kind of doubt they did. At some point her mother said something about organizing Anne’s room at the college so it would be nice when she got out of the hospital. Well, I thought, if Mom gets to that room before I do she’s certainly going to find out that Anne has boyfriend — what with my guitar and my books and my clothes all over the place.

The three of us sat there for a while, awkwardly. Waiting. Waiting. Waiting. There was absolutely nothing to talk about.

An unexpected call

I don’t remember how we had been sitting there before I was paged over the hospital public address system:

“John Sundman, please pick up any white courtesy telephone.”

I can’t tell you how trippy it was to hear that announcement. I felt like I was hallucinating. Who could possibly be paging me? What could be so important? I knew it wasn’t the surgeon; if he had wanted to talk to me he would have come to the waiting room. And besides, not enough time had transpired for the surgery to be over.

Unless, of course, something really, really bad had happened. I tried to put that possibility out of my mind.

I must have realized that any number of people might know that I was at that hospital right then. But what could possibly induce any of them to call me there?

A scary thought occurred to me: Could it be the police? Had that kid whose keys I dropped in the snow reported me for attempted grand theft auto? It was certainly possible.

Out in the hall I found a white phone on the wall. I tried to steady my nerves, to prepare myself. I lifted the receiver and was connected to the hospital operator. She told me that my father had called to say that I needed to call home as soon as I could.

My father?! Now I was really freaked. How could my father possibly have tracked me to St. Luke’s hospital in New Hartford, NY? Remember, for the prior few weeks I had been living in a storeroom — there was no phone there. And then, only a few days before Anne collapsed in the Hamilton gym, I had moved to her room. But that was our secret. I hadn’t told a soul. My father absolutely would not have known to call a phone in Anne’s dorm.

What number had he called that led to him finding me here, at a hospital, in New Hartford? And why? What was so important that he would have me paged there? I could only imagine that something truly terrible had happened.

Special Delivery

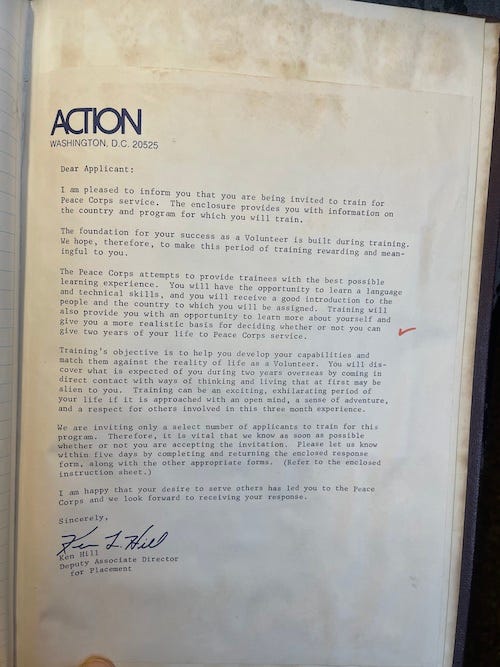

“John,” my father said. “A package came for you. Special delivery. I opened it. You have been accepted into the Peace Corps and offered a position in Senegal, in French-speaking west Africa. But you only have five days to accept the placement or they’re going to offer it to somebody else. So I thought I should tell you right away.”

He then proceeded to read the description of the position I was being offered: I was to be an animateur rurale, an agent for rural development working in conjunction with the government of Senegal on agricultural, public health and infrastructure projects, based in a small, under-served village — someplace with no running water, no electricity, no paved roads.

It was only exactly the kind of situation I had dreamed about since I first heard about the Peace Corps when I was in sixth grade. It was absolutely perfect, a dream come true.

And now I would walk away from it. It was childhood dream, nothing more. Poof! Gone, just like that.1

It was god-damnedest, mother-fuckingest, cruelest joke I could imagine. It was as if the universe was saying to me, “How about that, John. You’ve been going on and on about how you wanted to get out of the College Hill bubble, out into the ‘real world.’ Well is this what you wanted? Is this shit real enough for you yet? Your girlfriend’s life hanging by a thread, her parents giving you the hairiest of hairy eyeballs in a waiting room about the size of a bathtub, you just tried to donate blood twice in one week like a crazy person, your father is paging you to tell you that your whole world is upside down. Is this real enough yet? Just let us know, ‘cause there’s plenty more ‘real world’ where this came from.”

In a trance I walked back to the waiting room near the O.R.

One final dose of reality

Eventually the surgeon came to the door. He told me and Anne’s parents that Anne had pulled through that it looked like she was going to make it. Her parents moved to go with him to see Anne, but the doctor said, “Right now she only wants to see John.”

Anne looked as you would expect, lying on that ICU bed, with all manner of tubes and wires going into and out of her exhausted, immobile, just-barely-alive body.

I had never seen anything so beautiful in my entire life.

She looked up at me with a wan smile and said, ‘Sorry.’

So I sat down next to her and held her hand and told her all that had just transpired, saving the Peace Corps stuff for last. After I had told her everything that my father had read to me, she and I had this short exchange:

John: Well, it would have been nice, I guess. Anne: What do you mean? You're going, of course. John: No! Of course I'm not going. How can I go now? Leave you like this? I couldn't possibly. Anne: As long as I've known you, all you've talked about is how this was what you really wanted. If you don't go I'll never talk to you again anyway. So you might as well go. [This is the last straw. It is more than I can deal with. I am underwater in hurricane surf being pulled in fifteen different directions at once. I am almost out of air. I have no idea which way is up. A monstrous wave slams my head into the sand. I cannot make sense of anything. I am actually going to drown. But I don't drown. Somehow I break the surface, I take a breath. A few words squeak out of me.] John: Really? If I don't go to Africa you'll never talk to me again? Anne: Really.

And with that she turned her face away from me.

At that precise moment, in some impossibly distant galaxy, two neutron stars slammed into each other with a force that cannot be comprehended by our puny human intellects.

Astral whatnot

Here is page one of The No-Norton Interminglement:

If I were John and John were Me, Then he'd be six and I'd be three If John were I and I were John, I shouldn't have these trousers on.

The entry in the annotated credits for this page reads, “‘A Thought’ from A.A. Milne’s Now We Are Six (copyright 1927, 1955). Corporate identity theory.”

By ‘corporate identity theory’ Anne meant the notion that she and I were different beings housed in separate bodies, which she took to be ridiculous, as we had clearly fused into one soul-entity by the time we said our goodbyes (after going out the night before my departure for a cognac toast at the Rok).

Sometime that spring she began saying that on the night that Nemo died his soul must have come into me — and thus into her as well (since she & I were fused). Nemo’s nickname was ‘Snake,’ and that word now became a kind of ritual holy magic word for us. I could just think of something, and then think the word ‘snake’ and she would get my thought, telepathically.

Did she really believe in astral planes and transmigration of feline souls and all that New Age woo-woo telepathy crap?

Did I?

No. Of course not.

Well, maybe a little. But not really. Only kinda-sorta. {{Snake.}}

On the inside back cover of the Intermiglement Anne pasted the letter announcing my acceptance into Peace Corps.

Epilogue

Obviously some things changed between me and Anne. Her coming to realize that she was queer had a lot to do with that. She and Jane made a life together for quite a while.

Anne and I talk from time to time, or send an email — or just rap on a hard surface and whisper ‘Snake’. We’ve gone as long a dozen years without communicating at all; the last time I saw her in person was in 2002. Before that it was around 1988. It’s been fifty years since that day in New Hartford. Fifty years is a long time. Things change. Just ask Mick Jagger.

A year after returning home from Senegal I began graduate study at Purdue, and in January 1977 I went back to the Senegal River valley for 8 months of field research among the farmers there. It felt like home.

At Purdue I had to learn some math and some computer programming, things I had avoided at Hamilton. That background allowed me to get my toe in the door of the computer/software world — a vast realm where I’ve been happily challenged for much of my professional life.

And at Purdue, of course, I met Betty. Life-changing? Whoo-boy.

Counterfactuals are an idle business, but had I not gone to Africa I don’t think things would have gone well for me — or for me and Anne as friends. I think I would have become resentful and bored. I still had too much growing up to do. In telling me she would never talk to me if I didn’t accept that Peace Corps invitation and then turning her face away from me Anne saved my life. I do believe it.

And I can tell you this much: if the situation had been reversed, if it had been me who was that patient in an ICU just an hour out of surgery and Anne had been the one saying that she would be leaving me for two years, I would have said, Baby please don’t go, baby please don’t go, baby please don’t go.

So thank you, Anne. Thank you for saving my life.

And thank you for being a founding subscriber to Sundman figures it out! More of my readers should be like you! MWAH!

My friend Ed, in preparation for the 50th reunion of the Hamilton class of 1974 has been asking people for stories of that last spring on the Hill, as we prepared to go out and meet the world. So, Ed, how’d I do?

I do understand that this kind of living arrangement does not meet most people’s definition of ‘a dream come true.’ No matter; it met mine.

You hit a grand slam John. Well done. Star-crossed lovers on the Hill.

By the way, I never knew the Rok sold cognac.

What a remarkable, fearless, selfless young woman, that Anne. That's what love is all about.