Welcome, new readers

Sundman figures it out! is an autobiographical meditation, in the spirit of Michel de Montaigne, of a 71 72 year old guy who lives with his wife in a falling-down house on a dirt road on Martha’s Vineyard that dead-ends into a nature preserve.

Incidents, preoccupations, themes and hobbyhorses appear, fade and reappear at irregular intervals. Such hobbyhorses include the convergence of biological & digital technologies; philosophies of mind; coincidence and fate; firefighting; nostalgia for a small village in the valley of the Senegal River; hacking (bio, hardware, software, infospace. . .), literature & literary theory; existential dread, eros & thanatos; and quasi-religious cults of Silicon Valley. If you like this essay, I suggest checking out a few from the archives. These things are all interconnected.

Précis

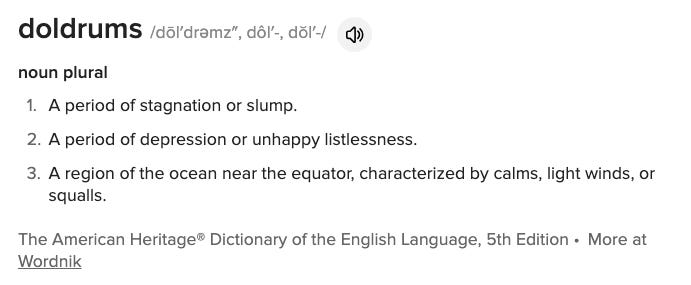

This post is about literal & metaphorical decompression sickness — aka ‘the bends’ —& the building of bridges & the doldrums I have found myself in since my last Sundman figures it out! post a month ago, and the odd — hopeful but somehow threatening — feeling of decompression I’m experiencing now that some, but emphatically not all of those pressures have dissipated.

It’s about coming to grips with the results of the election, and about various ways to look at the so-called ‘fall’ of the Berlin Wall in 1989 — some of them helpful, others not so much — and about the novelists Henry Roth and Jean Rhys & the function of writers in desperate times, and about a bouquet of flowers my wife & I once gave to a 19 year old woman who lived on the third floor of an allegedly haunted house.

I chose to write about doldrums and the bends not merely as a way to give myself a kick in the pants, to tell myself to snap out of it, damn you, John! — but because it’s my impression that many of us have been dealing with a period of ‘depression or unhappy listlessness’ since November 6th, 2024. Maybe this essay will help you a tiny smidgeon as well?

Am I really out of the doldrums? The evidence is contradictory. Point: I have published this essay and you are reading it. Counterpoint: I started writing this unambitious essay on my72nd birthday, intending to finish writing it in two hours’ time. But that day is already a more than week behind us, fading into the rearview. So let us see what we shall see.

Somerville, Radiohead, Bends

After I got knifed in Boston’s Dorchester neighborhood in the spring of Year of Our Lord Fred 2000, when I was working at Curl, a fucked-up Kendall Square software startup that was spun out of an MIT computer science fever dream, I moved to a room in a house on School Street which overlooked the parking lot of Somerville High School, not far away from Somerville Public Library.

I shared the house with a bunch of Harvard & MIT grad students half my age. From there, intermittently over the next 4 years, in all weathers, I rode my bicycle to various gigs in Boston and Cambridge, going home to Martha’s Vineyard on weekends, and sometimes for longer stretches, to be with my wife & whatever of our kids happened to then be at home.

I was often profoundly lonely. I hardly ever even saw my housemates; they were rarely there.

I got a Somerville Library card & checked out a book or two every once in a while, but mostly I used the card to check out music CDs. That’s how I first heard Radiohead. I really liked their album ‘The Bends,’ the title song in particular. I guess it resonated with my unhappy listlessness:

Where do we go from here? The planet is a gunboat in a sea of fear Ands where are you now when I need you?

‘The bends,’ is a colloquial name for decompression sickness.

Wikipedia:

Decompression sickness (DCS; also called divers' disease, the bends, aerobullosis, and caisson disease) is a medical condition caused by dissolved gases emerging from solution as bubbles inside the body tissues during decompression. DCS most commonly occurs during or soon after a decompression ascent from underwater diving, but can also result from other causes of depressurisation, such as emerging from a caisson, decompression from saturation, flying in an unpressurised aircraft at high altitude, and extravehicular activity from spacecraft. DCS and arterial gas embolism are collectively referred to as decompression illness. [. . .] DCS often causes air bubbles to settle in major joints like knees or elbows, causing individuals to bend over in excruciating pain, hence its common name, the bends.

Although exploration of the effects of extreme changes in ambient pressure go back at least as far as Robert Boyles’ observations of snakes in vacuum jars in 1670, and although some legitimate research on the effects of rapid depressurization was done from 1670 up through the 1800’s, it wasn’t until 1900 that the cause of the bends was finally found, when Leonard Hill used a frog model to prove that decompression caused bubbles of dissolved gasses their tissues and that recompression resolved them.

Bridges

Here is a picture of the Eads Bridge, one of the first places that many simultaneous instances the then still mysterious phenomenon of the pains were observed:

The Eads Bridge is a combined road and railway bridge over the Mississippi River connecting the cities of St. Louis, Missouri, and East St. Louis, Illinois. It is located on the St. Louis riverfront between Laclede's Landing to the north, and the grounds of the Gateway Arch to the south. The bridge is named for its designer and builder, James Buchanan Eads. Work on the bridge began in 1867, and it was completed in 1874. The Eads Bridge was the first bridge across the Mississippi south of the Missouri River.1

During the construction of the Eads Bridge, 15 workers died of the bends, two more were permanently incapacitated, and an additional 77 workers experienced severe symptoms.

The Brooklyn Bridge is also associated with mass occurrences of the bends. Construction began in 1870 and was completed in 1883, during which time more than 101 workers were treated for so-called ‘caisson sickness,’ including its chief engineer Washington Roebling, who never fully recovered from it.

I need to wash myself again To hide all the dirt and pain 'Cause I'd be scared That there's nothing underneath And who are my real friends? Have they all got the bends?

Sargasso Seas

The Sargasso Sea is associated with the doldrums; some people even conflate the two phenomena. Wikipedia:

The Sargasso Sea (/sɑːrˈɡæsoʊ/) is a region of the Atlantic Ocean bounded by four currents forming an ocean gyre. Unlike all other regions called seas, it has no land boundaries. It is distinguished from other parts of the Atlantic Ocean by its characteristic brown Sargassum seaweed and often calm blue water.

The sea is bounded on the west by the Gulf Stream, on the north by the North Atlantic Current, on the east by the Canary Current, and on the south by the North Atlantic Equatorial Current, the four together forming a clockwise-circulating system of ocean currents termed the North Atlantic Gyre. It lies between 20° and 35° north and 40° and 70° west and is approximately 1,100 kilometres (600 nautical miles) wide by 3,200 km (1,750 nmi) long. Bermuda is near the western fringes of the sea.

During October, 2024, while mired in my own doldrums, I finally got around to reading Jean Rhys’s stunning novel Wide Sargasso Sea. It is one hell of a book & I highly recommend it — although, like all of Rhys’s novels, it can be really, really depressing.

Rhys conceived of Wide Sargasso Sea as a prequel to Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre, about which more below.

Haunted house Berlin Wall roses

In 1989 my wife Betty & our three children (ages 8, 6, 1) & I lived in an allegedly haunted mansion in Gardner, MA — a glorious old white elephant with three fireplaces, a slate roof, copper downspouts, ceilings of stretched canvas, and plumbing that provided so many adventures (as chronicled in Sundman’s Awful Mistake, among other SFIO! essays).

In those faraway times I was working for Sun Microsystems and flying from Boston to San Francisco a dozen times or more each year en route to Sun’s HQ in Silicon Valley. Betty was spending a lot of time at The Elephant’s Child, the children’s book and toy store that she owned in Gardner. The demon toxoplasmosis, our Pazuzu, had been mostly quiet for a few years, lulling us into complacency. Our lives seemed somehow on an even keel. But with both Betty & I working, arranging for childcare was a challenge.

Our house had a third floor with two bedrooms and a bathroom that we never used. Although Betty’s store wasn’t yet breaking even, my salary was good, so, feeling flush, we contacted an au pair agency, and pretty soon a lovely 19 year old woman from Munich, Germany — we can call her ‘Anna’ — was a member of our household.

On November 9th, 1989, the opening of the Berlin Wall was the only thing anybody was talking about at the office. It was the only thing anybody was talking about on the radio.

On the way home from work I stopped and bought a dozen roses for Betty & I to give to Anna, saying. ‘You will never forget this day. Someday you’ll be the age that we are now, and you’ll look back on it.’ The six of us — three adults and three children — migrated to the TV room. All regular programming had been cancelled. The only thing on TV was Berlin, Berlin, Berlin.

My worries, a brief recapitulation

I said at the outset of this essay that for some while I have been beset with worries — some personal, some shared with hundreds of millions of fellow humans, possibly including your own dear self — and that these worries seem to have gotten me down more than I’ve been willing to admit to myself. Keeping me from, among other things, posting with any regularity to this chronicle. Which, I do have 75 paying subscribers to this thing, and if you are one of them you are indeed entitled to get something for your money, which I have not done sufficiently lately, wherefore I apologize.

I shan’t go into my personal cares and concerns other to note that some of them are, as of November 25, 2024, thank Fred, considerably less pressing than they were one month ago. The ambient pressure, that is, is much less than it was quite recently.

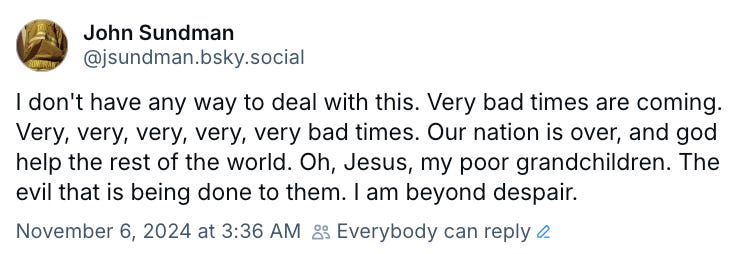

But as to the other, broader concerns, here’s what I posted on Blue Sky the day the election results were known:

To understand why I felt that way, see my October 16 post Surfing the Cataclysmic Technopotheistic AI-Turbocharged World-Fascist Tsunami: Finding courage together in the vortices of our days , which enumerates all the bad things I feared would result from Trump being reelected president.

In that essay I included a photograph of spectators observing, from a safe distance, a surfer on a terrifyingly large wave, to which I gave the caption, “Look closely. Do you see that tiny figure surfing down the face of that wave off the coast of Nazaré, Portugal? That is you and me, together.” I expect that virtually everybody who sees that photo experiences a least a twinge of terror. I’ve actually surfed hurricane surf (Agnes, 1972, Long Beach Island, New Jersey), where the waves were no more than 1/6 that size, and that was one of the scariest experiences of my life. Those waves in Nazaré? Oh my dear God.

But while I feel that everything I wrote about in that ‘tsunami’ essay still obtains, (perhaps you’ll read it?) I’m not reprising its argument here and I’m not including that photo in this post. Because although I acknowledge the fears that drove me to write that essay, fears which are still very much part of my everyday existence, I’m determined to emerge from my fetal crouch, my unhappy listlessness. There is no time left for wallowing.

The danger of ‘Fall of the Berlin Wall’ nostalgia

Timothy Snyder is a professor who studies how authoritarian movements form, seize power, and (sometimes) fall. His books include On Tyranny and On Freedom; they’re good. He recently wrote an essay called The Berlin Wall Never Fell, about putting the so-called ‘fall’ of the Berlin Wall into its proper historical context.

Thirty five years ago today, the Berlin Wall did not fall.

I realize that I am running against the torrent of anniversary remembrances here. And no doubt you are thinking: he means this metaphorically; he means that some mental barrier remains between East and West, or perhaps between eastern and western Germany.

No, I mean that, quite literally, the Berlin Wall did not fall. It did not fall thirty-five years ago today. It never fell. The "fall of the Berlin Wall" is a literary device, not a historical event.

And that we have chosen a false image to stand for a moment of liberation reveals a problem.

In that essay, Snyder reminds us that before the events of November 9, 1989 in Berlin, the Solidarity movement in Poland had laid the groundwork, had provided the example for how to shake off Soviet oppression:

Words matter. Pretty much everyone says "the fall of the Berlin Wall" as a shorthand for the "the end of communism in eastern Europe." But something that never happened cannot be a source of an actual memory. It cannot teach us, for example, how authoritarianism is resisted.

The image of a wall falling transforms a complicated history into a simple moment. But when we embrace that image of something that never happened, we lose everything that we need to remember, everything that is human and interesting.

In other books and essays Snyder makes concrete proposals, based on his decades of study of what does and doesn’t work to reclaim and preserve democracy and freedom in the face of authoritarian and fascist movements, about how we should prepare to resist.

Here, in his ‘Berlin Wall’ essay, he does not go into such specifics. Here he simply he calls on us to base our strategies on historical facts, not on simplistic romantic imagery, like that of a wall falling down. (Or maybe even of a terrifying rogue wave?)

Snyder’s ‘Berlin Wall’ essay is a call to action in the face of the impending inauguration of the fascist Donald Trump. I am trying to heed that call.

Cruel ironies

If you give a starving person leave to eat whatever they want it may destroy their horribly out-of-kilter metabolism and kill them. This is called ‘refeeding syndrome.’ So too with the laborers working one hundred and fifty years ago in pressurized caissons deep beneath the Mississippi and East Rivers, digging foundations for majestic bridges that are carrying traffic right this very minute. An account, via Wikipedia, of a worker on the Brooklyn Bridge:

Compressed air was pumped into the caisson, and workers entered the space to dig the sediment until it sank to the bedrock. As one sixteen-year-old from Ireland, Frank Harris, described the fearful experience:

"The six of us were working naked to the waist in the small iron chamber with the temperature of about 80 degrees Fahrenheit: In five minutes the sweat was pouring from us, and all the while we were standing in icy water that was only kept from rising by the terrific pressure. No wonder the headaches were blinding."

When those workers’ shifts were over, who can blame them for wanting to get back to the surface as soon as they could? Yet it killed them.

Jean Rhys and my greatest problem

Towards the end of my earlier three-part essay My greatest problem, I discussed the career of the novelist Henry Roth. In particular I wrote about the sixty year gap between the publication of his first novel, Call it Sleep (1934), and his second, A Star Shines over Mt. Morris Park (1994). In that essay I called Henry Roth ‘my literary hero, because he managed to pull himself out of a decades-long funk and finish, in grand style, the work as an artist that he had set out to do as a young man. His grand ambition was to document and reconcile the conflict between a person’s inner need for autonomy and the often oppressive claims on them of the tradition from which they came — in Roth’s case that was the Jewish culture of the Lower East Side of New York in the early 20th century.

As remarkable as was Roth’s return from obscurity, Jean Rhys’s literary phoenix act was, it seems to me, even more impressive. She published Wide Sargasso Sea in 1966 at the age of 76 — some 27 years after the publication of her most recent prior novel, Good Morning, Midnight.

But her exile from the culture from which she came — the Creole culture of Dominica, in the West Indies — and in which never felt welcome — was even more extreme than Roth’s. And as a woman, and a poor one at that, she had to deal with all manner of abuse and oppression that men like Roth simply did not.

From the introduction to Jean Rhys: The Complete Novels, by Diana Athill:

There was still almost no money, her husband’s health gave way, and the pressure she was under caused Jean to be (as she said in a letter to an old friend), almost always “two days drunk, one day hungover.”

For nearly thirty years the literary world saw nothing of her, and the misery of those years was profound. But all that time, inch by slow and painful inch, her next book was growing within her.

Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre had always disturbed Jean. She may not be the only reader of that novel to dislike its heroine, but is probably the only one to identify with Mr. Rochester’s mad wife from the West Indies. [. . .] What had really happened to that unhappy bride onto whom Brontë had projected such a cruel — such (in Jean’s eyes) a typically English — version of the story?

From that question grew Wide Sargasso Sea, the novel created over so many years, against such heavy odds, with which she made her come-back in 1966.

More than just a brilliant, deep, disturbing novel — a book that makes you think and feel, as any novel worth reading should do — Wide Sargasso Sea is a testament of uncompromising courage: Rhys’s willing herself out of her own becalmed waters.

Where do we go from here? The planet is a gunboat in a sea of fear My baby's got the bends We don't have any real friends, oh no!

Rowing out of own Sargasso Seas

A few days after the election, somebody — I don’t remember who, or where — posted — on Blue Sky or in substack notes, or someplace else — words something like these:

If you are a writer, especially if you are a novelist, you may be wondering What’s the point? But in scary times people have always depended on writers, storytellers — novelists in particular — to get them through. Take care of yourself, for you are going to be on the front lines.

Maybe that’s hyperbole, but if it is, so be it; I don’t care. I’m taking it as my credo.

By November 1989, writes Timothy Snyder,

Poland had already formed a post-communist government. And that of course is the Polish gripe with the whole "Berlin wall falling" story. Poles will want you to know that Poland was more important than East Germany in the history of the end of communism. And that is very true. But the crucial thing to remember is what Poles did. In the face of dictatorship they found concepts of cooperation and lived them.

Athill’s introduction to Rhys begins like this:

In the years when I knew Jean Rhys — the last fifteen of her life — she often spoke about how much she wanted to “get things right:” to be as true as possible in her writing, to place, speech, mood, the taste and texture of experience, and to achieve this precision without — as she once said in a letter — “any stunts.”

“We cannot change the world all at once.” Timothy Snyder says. “But we can change the way we think. We can clear away the clichés and make ourselves more lively. We can work together and then, when other things are in motion, be ready to turn the change in the right direction.”

Years ago I was crybabying in an email to my friend the great novelist Geraldine Brooks about being ‘blocked,’ to which she replied, “When there is no wind, row.” I wrote that on an index card & taped it just below the skylight over the desk in my attic office. Next to it I placed a postcard I had made years ago, with covers of my novels. Together they are a daily reminder that either I take seriously that I am a novelist with an important job to do, or I don’t.

I do.

So this is my promise. I will finish the novels I’ve been promising some of you since forever, and I will write others after them. I will post essays here regularly; there will be no more month-long gaps. I will do my best to capture our world with (Diana Athill’s word) precision, and without (Rhys’s words) any stunts.

Today I am once again putting my oar into the water.

All info about the Eads & Brooklyn bridges, & about compression sickness is from Wikipedia. I copypasted some of it verbatim & edited the rest.

Welcome back.

Well said John. For what it's worth, what you write (in essays and in books) matters to me. The timeline, not so much.