A Scared Firefighter up in the Bucket, part one

Warning: Electrocution Hazard. Plus! AI storytellers come of age

Preliminary obligatory

Despite my characterization of Sundman figures it out! as a weekly newsletter it has been a bit of a while since my most recent post. Like, a month(?). Ooops!

I still do plan to drop one of these things on the average of once per week, but there will be some irregularity in their arrival, reminiscent of that of the prime numbers, based on the vagaries of whatever. Today I send you A Scared Firefighter, up in the bucket, part one. Parts two and three of this essay will go out within the next 4 days. Thus balance in the universe shall be restored. He said knowingly. Selah.

From firefighting to chatGPT in my squirrel brain

I was a firefighter for 10 years, a proud member of the company of Tisbury Tower 1, AKA Tisbury 651, AKA ‘the Bronto’ (short for brontosaurus), and over that whole time I was only scared once during firefighting operations.

I’m going to tell you the story of how a sudden fear gripped my heart as I stood on a firefighting platform 30 feet in the air above the smoldering remains of what had been a person’s home, feeling both sad for their loss and deeply satisfied with the work I had done over the prior crowded hour. I will tell you how, with the sun rising over Chappaquiddick ten miles to the east, the fire out, I was preparing to steer the Bronto’s boom to the ground when I happened to glance at my boots and saw something on the steel platform on which I stood that made my blood run cold. I will tell you all about that, but it’s going to take me a little while to get there. Here’s why.

Whenever I think about that one incident up in the Bronto’s bucket I think about that time back in 2005 when I went to dinner with the cognitive/computer scientist Douglas Hofstadter and the philosopher of consciousness Daniel Dennett. As you’ll see, those two events are entangled in my memory such that I can’t properly convey the terror I experienced at that fire scene without first talking about the whole Hofstadter-Dennett thing, which, for reasons we’ll go into shortly, unavoidably involves a detour into a discussion of some recent developments in artificial intelligence. So, you know, I guess what I’m saying is here comes another Sundman Tristram-Shandyish shaggy dog story, lucky you.

Structure Fire

Sometime around 4 AM, October 28, 2011, my pager woke me with the screeching ‘alert’ tone followed by Dispatch calmly intoning “Tisbury firefighters: respond to structure fire, 59 Edgartown Road. . .” an address about one mile from my house.

‘Structure fire’ are two words to wake you up. Unlike ‘car fire’ or ‘chimney fire,’ or, goodness knows, ‘automatic alarm,’ they mean that chances are good that you have some actual serious firefighting in your immediate future.

I was on my bicycle riding to the scene within 4 minutes — wearing my PJ’s; other than donning socks and sneakers & a sweatshirt I didn’t bother to dress — time is of the essence in the fire service (we had no car that year; that’s another story). I got to the fire just as a couple of guys were deploying the Bronto’s outrigger jacks in order to lift that 80,000 pound machine off the ground.

I tossed my bike out of the way & grabbed my gear bag from a Bronto side compartment just before it would have gotten beyond my reach as 651 went up on its jacks. The fire was cackling and flames were coming out of all the upper-story windows. I could feel the heat and hear radios over the din of diesels. Engine 3 was on scene & some guys were dressing a hydrant. Engine 1 pulled up & I could see Engine 2 coming up the Edgartown Road, lights flashing, siren sounding. Guys were calling to each other — some geared up, some still in street clothes. I put on my turnout gear, threw on an air pack and found Captain. Captain tells me, “You’re going up in the bucket with Murphy.”

Well now. Happy day. Up in the bucket at a working fire. I love that shit. I felt truly serene.

One doo tree four five eeks e-grek zed

I spent the summer of 1971 working in a spare-parts warehouse near Place d’Italie in Paris, France. I had a French co-worker there, I’ll never remember his name, who tried for months to learn how to count to ten in English. His problem was the number six. It derailed him. He would sail through one through five, but when he got to six he would pronounce it ‘eeks’. (‘Seeks’ would have been Okay, but he never managed to put the ‘s’ there. So too, I have so many missing ‘s’ ’s in my own thought processes. Alas for those missing esses!) Anyway, ‘eeeks’ is the French pronunciation of the letter ‘x’, and as soon as he said ‘x’ he would skip a groove and recite the last part of the alphabet, x,y,z. It was hard-wired. There was nothing he could do about it. In his mind those sequences — the beginning of the natural numbers in English and the end of the alphabet in French — were entangled.

So too, I have entangled sequences in my mind, such that when I think of that dinner with Hofstadter and Dennett, I inevitably recollect the late Hugh Loebner’s crazy or not-so-crazy quest for a robot that could pass the Turing Test by convincing a person that the bot they were talking with was human.

You see, in 1990 Loebner created an annual chatbot contest and enticed entrants with the promise of a grand prize of $100,000 and a medal of solid gold for the first bot that passed as human. In 2003, for Salon, I wrote a long essay about Loebner and his contest and prize. And it was that essay in Salon that had brought about my invitation to that Hofstadter-Dennett dinner in 2005 that is entangled in my squirrel brain with that fire in 2011. It’s almost as if these seemingly jumbled memories are actually some kind of eternal golden braid.

Generation Generative and its antecedents

We’ve been hearing a lot lately about ChatGPT and Sydney and their ilk, the ‘generative pre-trained transformer’ AI programs that can, given appropriate prompts, create essays, scripts, stories, poems and the like that are, often, astoundingly well done — human-like, superhuman, even: ChatGPT has passed exams required of would-be doctors, lawyers and candidates for Ivy League MBAs, not to mention producing Peter Brand-like analyses of every Major League Baseball player, and more, so much more. Many humans can do some of the things that those AI programs can do, but nobody can do all of them.

Other generative AI programs have been producing visual and musical art and writing sophisticated computer code and attacking, and often mastering, virtually every other variety of human intellectual endeavor.

With these startling developments — computers besting humans in heretofore human-only ‘thoughtful’ activities — have come, of course, all manner of rumination & breathless commentary on the immanent eclipse of our (human) kind by artificial intelligence, and the philosophical, ethical, practical implications of machines that can perform as well at impersonating (very smart and talented) humans as chatGPT does today.

The experience of reading smart, subtle essays written by AIs, or walking through complex AI-written computer code, or looking at a perfectly drawn image produced by AIs in response to a tricky prompt (e.g. “draw a picture in the style of Joos van Cleve of Frodo Baggins meeting Patti Smith at CBGB’s”), can be a bit unnerving.

In some people, such experiences are beyond unnerving; they have even been known to induce a new and most unwelcome sort of existential queasiness.

But existential queasiness is neither new nor unwelcome to your humble substacker. In fact it’s my default condition: I seek and embrace existential queasiness, I try to get into it — much as a Repo Man spends his life trying to get into tense situations that ordinary people strive to avoid.

A little more about that essay in Salon

My Salon story (“Artificial Stupidity” (a title chosen by my editor, not me) part one, part two) was not merely about Loebner’s quest. It was also about the apparent state of academic artificial intelligence, “AI,” in 2003, and about the hobbyists and cranks who wrote chatbot programs to compete for the prize money that Loebner had put up for the first bot that could pass Turing Test, and about how academics like Dennett and MIT’s Marvin Minsky had at first embraced Loebner’s contest —they had actually helped organize and promote it — but later came to view it with scorn and derision, and withdrew their endorsements.

But while Dennett and others in academia said that they had disowned the Loebner Contest because it had become clear to them that Hugh Loebner was nothing but a publicity-seeking charlatan who was impossible to work with, and whose competition did nothing to advance the field of artificial intelligence, I offered a different take: I said that it seemed to me that academics had quit participating in the Loebner contest because it had revealed that their chatbot programs, written by the greatest minds in computer science, fared no better at the Turing Test than chatbot programs written by self-taught hackers. They quit participating in Loebner’s contest, I said, because it was making them look foolish.

At the restaurant in Cambridge that night in 2005 Hofstadter loved quoting from my essay, especially the parts where I had made fun of Dennett. (You can read a contemporaneous account of that event, “Mindful of Philosophy,” on my ancient blog Wetmachine.)

Don’t touch me, I’m a real live wire

The MV Times has a short but informative article about the fire. The two paragraphs below contain some key points that we’ll revisit in part two of this essay, coming soon.

The house is set back about 30 feet from the street and there is considerable growth of vegetation on both sides of it, which made access difficult for the firefighters, Chief Schilling said. To make matters worse, the power line to the house burned off before the firefighters got set up.

“That added a hazard and further restricted our ability to fight the fire,” Chief Schilling said. “It was very difficult to operate around a live wire, which was on our best access point.”

Now the thing of it is, the guys on the ground knew that that power line had burned off the house & was now a live wire. They knew to make a wide berth around it as they stretched their hoselines & prepared to put some wet stuff on the hot stuff. But Murphy and I, up in the bucket, we didn’t know that. We never got the memo.

A porch garden

You know that scene towards the very end of Herman Melville’s novel Whitejacket, where the narrator (who is named after his garment) has lost his hold on the ratlines 100 feet above the deck and has incredibly lucid thoughts as he tumbles to what he expects to be his death? Well, up in the bucket that morning I had a similar experience when confronted with my own mortality. My incredibly lucid thought was this: I thought about the garden my wife Betty recreates every spring and summer on our back porch.

I thought of the way that garden marks the rhythm of each year — much like the annual rains and flood mark the dieri-oualo rhythm in Fouta Toro, in the Senegal River Valley.

Evert spring I carry out those plants that we’ve wintered over indoors & I place them wherever Betty tells me to on the porch — at first close to the house & shade, later, after they’ve hardened a bit, out into the wider porch-world. Then we start our yearly visits to Heather Gardens and Middletown Nursery and Jardin Mahoney and every other garden supply place on Martha’s Vineyard to buy new flowering plants and starts for tomatoes and peppers and green beans, and some fertilizer and potting soil, and maybe a little statue of a frog or St. Fiacre. (Or an orb. No garden is complete without an orb.)

And then, all summer, with her snips and her watering cans and what-all else, Betty makes that porch into a little oasis. I find serenity there, almost like I do in the Bronto’s bucket at a working fire.

But all things must pass, and summer ends, and in the autumn when the first frosts are threatening I bring inside all those plants that we hope will have some chance of wintering-over indoors, and I take the other plants, the doomed ones, and toss them into a compost bin, or sometimes just into the woods behind our house.

That was my Whitejacket thought.

I will show you existential queasiness in a handful of chat

I almost forgot to say that one of the things chatGPT & its brethren & sistren are good at is computer-mediated text-based conversations, also known as ‘chat’. These generative AIs are the apotheosis of the chatbots that Hugh Loebner devoted much of his life, and a good portion of his wealth, to bringing about.

And in the next parts of this little essay, in addition to telling you all about what I saw from the aerial platform of Tisbury Tower One on that early morning in late October in 2011, I’m going to take you on a little tour of those generative chatbots. We’ll look at transcripts of some astounding chats, and we’ll take a peek under the logical hood to see how they work (to the extent that we even understand that), and how they mess with our minds and make us queasy as well.

But if these new-generation chatbots unnerve some people, I bet they wouldn’t have disquieted Hugh Loebner; I rather think they would have delighted him. But Loebner never saw the miraculous-seeming transcripts of these generative AI chats. He died in 2016, his prize unclaimed.

But the Loebner contest is a thing of the past; it has just withered away. Who knows what became of the $100,000 prize money? Not me. I wonder if anyone does. And I have no idea where the medal of solid gold that bears Loebner’s likeness on one face and that of Alan Turing on the other now is.

A Room with a View

The picture below is from 2017, on the day of my retirement, when I flew the Bronto for the last time. Normally there are at least two firefighters in the bucket when you go aloft, but that evening, on the apron in front of the firehouse, Captain said to me, ‘You want to fly it one last time by yourself? Go ahead. Take her up.”

And so I did. I rode it all the way up, one hundred feet. The sun was setting. I looked east, towards Chappaquiddick, and north, across Nantucket Sound to Falmouth on Cape Cod, and south towards Squibnocket and the Atlantic beyond, and west, where the sun was setting over Cuttyhunk. And then I rode it down and parked the bucket in its bed.

You can see how the entire machine is lifted off the ground on its metal jacks.

Yesterday evening I worked out in the weight room in the loft that overlooks the apparatus bay. It occurred to me to snap a few close-up pictures of Tisbury 651 to illustrate a few things. For example, here you can see another person’s gear bag in the compartment that used to hold mine. That red bag contains a jacket, a helmet, pants with boots inserted at the leg openings, gloves, a custom-fitted face mask, a hood, and a few sundry tools. A skilled firefighter can get their stuff out of the bag and get geared up, airpack included, in about two minutes.

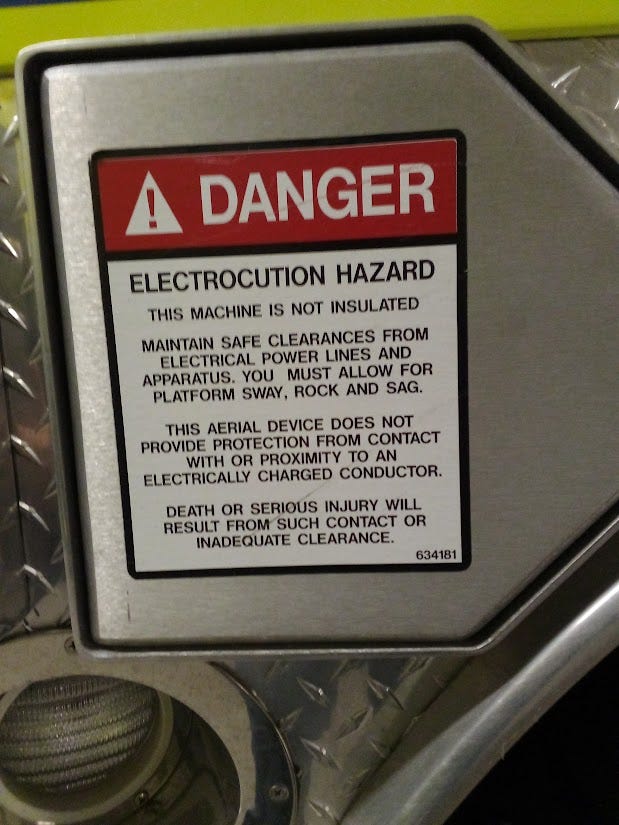

But wait. What’s that notice on that little door to the compartment that holds a spare air bottle? Let’s zoom in, shall we?

Oh. That’s good to know. Thanks.

I hope you’ll continue reading A Scared Firefighter up in the Bucket, when I post part two, coming soon, in which I’ll try to weave some of these threads together.

Wow, it’s like the serials at the Saturday matinees! Can’t wait till next week!

Looking forward to part 2. It's interesting to re-read the account of that dinner; within a couple of years, I'd be working at Amazon, where a 10,000 node system was no big deal.....