Shifted reading frames

In DNA, in assembly language, in jump rope songs, in general

New here? Howdy!

Welcome, new subscriber, to Sundman figures it out!, an episodic autobiographical meditation. Here, themes emerge, fade, reappear and interleave; incidents ramify and their import ( viz. purport; signification) sometimes changes upon being revisited. Therefore you may find that reading some of the earlier posts, according to your whim, will enhance your experience of reading this and subsequent essays.

Précis

A molecular biologist’s recent tweet about her lab’s discovery of a property of shifted DNA reading frames elicited some comments, in tweet form, from a computer programmer. I start by showing you some of these tweets, and then go on to explain that the biologist’s line of research and the programmer’s comments about it both interested me, but for different reasons.

The essay moves on from there, repurposing some words that I wrote for my Technopotheosis newsletter in February, 2021 (which in turn revisits a two-part essay I wrote for Salon in 2003 entitled How I decoded the human genome).

And then I extemporize on the concept of shifted reading frames more generally.

Also, there are digressions into topics that have nothing to do with any of this.

Some familiarity with high school-level biology will help you parse today’s post, as will a general familiarity with computer programming. But if you have only one or neither of these, don’t worry. If you’re motivated enough to have read this far you’re sharp enough to follow along. I won’t strand you, I promise.

Digression: Lessons from 23 Years as a Self-Publishing Novelist

I wrote a guest post on JaneFriedman.com.

I established an Amazon Advantage account and set off in my falling-apart car on a coast-to-coast book tour, pitching my book at hacker meets and scientific conferences, in Silicon Valley cafeterias, on street corners, and even at a bookstore or two. Over three weeks I sold enough books, barely, to cover my expenses. I made it back home by the skin of my teeth. I didn’t have enough money for a McDonald’s Happy Meal or one more tank of gas. I was defeated. I set aside my novelistic ambitions for good and got a day job, back in the world of tech, which I had left five years earlier.

I hope you’ll check it out.

Dr. Chlebeck’s observation

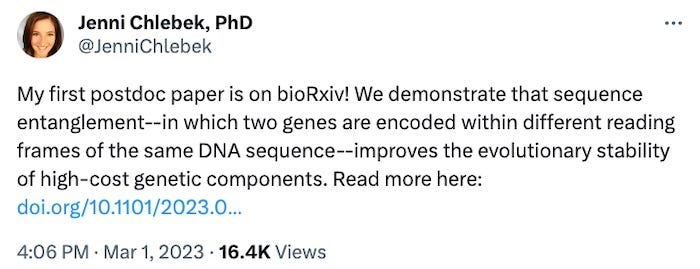

In early June I saw this months-old tweet over on the boy-wonder’s hellsite:

I followed the link to the cited paper, Prolonging Genetic Circuit Stability through Adaptive Evolution of Overlapping Genes, and read the abstract, which concludes

Overall, this work demonstrates the utility of sequence entanglement paired with an adaptive laboratory evolution campaign to increase the evolutionary stability of burdensome synthetic circuits.

You may find this an interesting bit of genetic engineering or not; you might wonder what kind of real-world utility (if any) this research might have; you might be intrigued by the poetic phrase “evolutionary stability of burdensome synthetic circuits;” you might not (yet) even have any idea what the hell she’s talking about.

But I think you’ll agree that Dr. Chlebek and her six co-authors said a mouthful.

Digression: jump rope!

Long time readers of Sundman figures it out! may be familiar with photos (including the one below, taken, ~2006, by (my friend since childhood) Ande), of the New Jersey farmhouse in which I resided with my parents, and my father’s parents, and my six brothers and sisters (and, until he went into the Marines, Uncle Harry) from 1952, the year I was born, through 1965, when we moved to the new house up the street. Within days after Ande ignored a bunch of No Tresspassing signs to take some two dozen photos of the little house I used to live in that house was gone — along with that companionable trio of gorgeous trees: silver maple, red maple, blue spruce — demolished to make way for a bland McMansion.

On summer evenings when I was eight or nine years old kids from the neighborhood would congregate at our house to play baseball in the pasture, or tag or hide and seek in the yard, or, often, to jump rope in our driveway. Here’s one of the songs we jumped to:

Fudge, fudge Call the judge Mama's gonna have a bay-bee It's not a girl It's not a boy It's just an ordinary bay-bee Wrap it up in tissue paper Send it up the elevator First floor, STOP Second floor, STOP Third floor, kick it out the door Mama don't want that baby no more

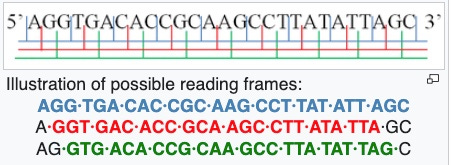

DNA reading frames explained in one picture and three sentences

Wikipedia: “In molecular biology, a reading frame is a way of dividing the sequence of nucleotides in a nucleic acid (DNA or RNA) molecule into a set of consecutive, non-overlapping triplets. Where these triplets equate to amino acids or stop signals during translation, they are called codons.”

Overlapping gene products result from the same sequence being read (and translated) in two different reading frames in the same organism, thus producing two different proteins from the same genetic source.

This is all the background you need to get the gist of Dr. Chlebeck’s paper about entangled genes, and in just a moment, after a few more preliminaries, I’m going to give you that gist so that we can finally get to the substance of this essay.

The wikipedia page on reading frames is quite good but it doesn’t mention that overlapping gene products were first reported by Frederick Sanger and colleagues in 1977. They discovered the phenomenon of overlapping genes read in different frames in the phi x 174 bacteriophage (a virus that infects bacteria) in the course of developing the so-called Sanger Method of sequencing DNA, for which Sanger was awarded his second Nobel Prize, in 1980.

Remember that year: 1977. That’s when overlapping gene products in bacteriophage were first made known to the world.

Now let’s talk just a little bit about some shifted reading frames in assembly language computer programming.

A programmer posits shifted reading frames in assembly language code

Months ago I copied the text of some tweets made by a self-described programmer (whose name I’ve lost track of) in reply to Dr. Chlebeck’s inciting tweet about entangled genes. I’ve condensed the programmer’s remarks into twp short paragraphs with some edits for clarity.

This scenario has a pretty close analogy in computers: it's as if you could set the program counter, which contains the address of the next-to-be-executed opcode, to a fractional value (56.5, say), causing it to interpret all instructions from then on as shifted by a nibble.

In practice no architecture would let you do this because it's bonkers, although you could get a similar result by loading the code into memory and just left shifting everything by half a word.

But you know what? Forget it. I’m not going to go into all the business of how a machine-language instruction, represented in assembly language as an opcode, is analogous to a codon in DNA’s language. It’s too convoluted and inexact and it doesn’t add much to this conversation. Those of you who know CPU architectures and assembly language program please leave a note in the comments if you want to discuss this further.

The only concept from assembler useful to the broader world is the no-op opcode. “No op” is short for ‘no operation.’ You use it to tell a CPU that for the time it takes to complete one computer instruction, the CPU should do nothing, exactly as if it were the plot for an episode of the TV show ‘Seinfeld’.

A no-op can come in handy in some programming situations, but it’s more generally useful in geek talk:

— Have you met the new boss? — Yeah. — Well? — A no-op.

By extension, this section is kind of a no-op in the context of this essay.

DNA sequence entanglement and a jump rope song

Unlike in 1977, technology now exists that allows the manufacture of any arbitrary sequence of DNA. This means that if you can figure out a DNA sequence that can be read in two different frames to produce two different proteins, you can easily construct that DNA sequence. What Chlebeck et al have shown is that if you do that (and insert that newly-constructed bit of DNA into the right place, and all that), under certain conditions, those genes are less like to mutate than they would be if the genes were on separate sections of DNA, that is, not entangled.

Here’s a picture of the driveway where we used to jump rope on summer evenings sixty years ago.

Cinderella dressed in yella went downtown to meet her fella. On the way her girdle busted. How many people were disgusted? One, two, three, four. . . .

What might be the practical applications of Chlebeck’s work? Who knows?

If you’re a research scientist you just do the research to understand how the world works. Sometimes it pays off spectacularly in terms of applications; sometimes it doesn't. Your research on gila monster saliva might lead to a breakthrough medication for diabetes. Or it might not. You never know. The justification for the research is the insight it gives into how the world works. If a cool application comes out of that somewhere down the line, that's just gravy.

But anyway, here’s a followup tweet from 3 months after Dr. Jenni Chleblek’s initiating tweet about evolutionary advantage of entangled genes.

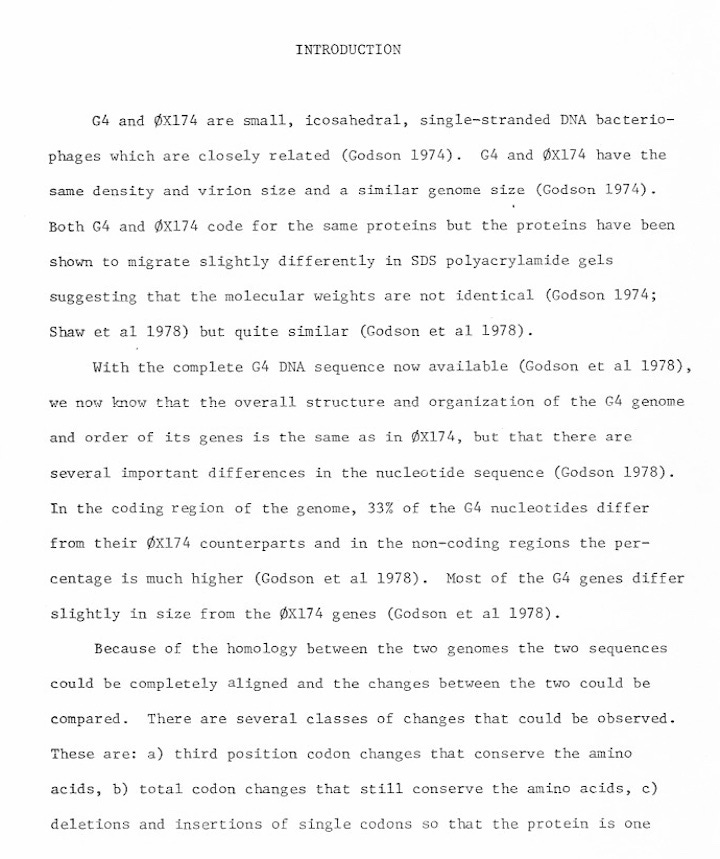

After Sanger, the babe

As discussed, in 1977 Fred Sanger published the first paper that mentioned overlapping gene products in bacteriophage. He got a Nobel Prize. (And he already had one! That just ain’t fair!)

Below, the introduction to what may actually have been second paper on overlapping gene products in a bacteriophage. It’s called Comparison of Overlapping Genes and Multiple Gene Products of the Small Single-Stranded DNA Bacteriophages Phi X 174 and G4, and it dates from early 1978, when so-called Sanger Sequencing (of DNA) was only a few months old, but already transforming the way research was being done in molecular biology laboratories all over the globe.

The new research was presented to a standing room only crowd (including James Watson & Francis Crick) at the Phage Symposium at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratories in 1978. Unlike Fred Sanger, the presenter of this research did not get a Nobel Prize.

OK enough of that boring science stuff, let’s cut to the chase: here’s what the author of that paper looked like a few months after presenting her research on overlapping gene products to the royalty of molecular biology in 1978. Ain’t she a doll? No wonder it was standing room only when she gave her talk! When I get my hands on a time machine that’s one of the first things I’m gonna check out.

So anyway now we’ve resolved the mystery of why a note on entangled genes caught my attention. I’m a sucker for anything having to do with research on overlapping gene products. It’s kind of a pavlovian thing, actually.

There’s a whole lot more to say about entanglement, of course. Quantum entanglement, for example. Entangled particles on a black hole’s edge, and Stephen Hawking’s black hole information paradox. Romantic entanglements. Christmas tree lights. Your girlfriend’s tangled hair that you patiently comb out sitting there by the fire as the radio does play “March of the Wooden Soldiers”.

There is enough entanglement in the world, both theoretical and actual, for a multi-part Sundman figures it out! series, I don’t doubt it. But that series is not for today.

Set Your Wayback Machine to October, 2003

2003 was the year my long two-part narrative on all things DNA appeared in Salon.

In the course of researching that article I travelled from San Diego to Boston and points elsewhere, talking with scientists, philosophers, bio-luddites, disability rights advocates and regular people as well. I sure put a lot of work into it for the fifty bucks or whatever it was that Salon paid me.

The first part of the essay bore the title I gave it, How I Decoded the Human Genome. The second part had a title that my editor gave it, One Vote for the New Eugenics. This title, alas, was based on an unfortunate misunderstanding of a comment made by my wife Betty.

In re-reading that essay for the first time in more than a decade I was happy with how well it has held up. Sure, there are some things that make me wince a bit, and one or two things I got wrong. But in general I think it's pretty darn good.

Here's a few paragraphs from the opening of part one:

I had come to San Diego looking for a deep understanding of the meaning of life, which I was planning to bottle and sell at a decent markup. I wanted to address the questions that have been implicit ever since Rosalind Franklin's crystallography revealed God's schematics for James Watson and Francis Crick to decode: What is a human being? What is our worth? Who decides?

But all I was getting was science, and that was bad. Now, science is OK, of course, for people who like that kind of thing. But I had come to the O'Reilly conference on a self-financed gambit to elbow my way into the moral-philosophy racket. I figured that if Bill Bennett and similar gasbags could make millions spouting mere platitudes and recycled 15th century theology, then I should be able to make a few large, at any rate, for genuine insight into ethical quandaries occasioned by 21st century breakthroughs in biological science.

Especially in 2003, the golden jubilee of Watson and Crick's seminal eureka. It was the proverbial Klondike opportunity, but in order to cash in I would need to come up with some salable wisdom that was predicated on an actual understanding of current DNA technology. So that's why I was sitting in Dr. Cooper's lecture and waiting for profound insight.

and here's a few more from the conclusion of part two:

Let's stipulate that here in Karl Rove's America, our moral universe is predicated on our economy, that our economy is predicated on consumerism, that consumerism is predicated on narcissism, and that the narcissist, the driver of our economy, is driven by the search for his or her own physical perfection and the derivative perfection of his or her own children, pets and other possessions.

Obviously this perfection obsession at the root of our culture is thoroughly enmeshed with sex, the DNA-driven urge each of us feels to find the perfect vector to propagate our own deoxyribonucleic heritage. We are biologically programmed to procreate, and, at that, to procreate with the best available evolutionary stock. In a capitalist system, that optimal evolutionary stock follows the money. In our world good looks and physical exceptionalism are supremely marketable commodities, as Michael Jordan can explain much better than I. Therefore America (along with its copycats) stands for nothing if not the moral imperative of its wealthiest, best-looking people to do a lot of fucking. I'm sure we can all agree on that.

As consumerism is our official state religion, and insofar as mucking about with DNA is clearly a religious or quasi-religious activity, it follows that the purpose of the billions of public dollars invested by the state in the Human Genome Project is to make perfect people. Or to be precise, the Human Genome Project furthers our demonstrated national values to the extent that it facilitates the creation of physically perfect people who buy lots of stuff.

A lifelong preoccupation with DNA and a myriad of unanswerable questions roiling my brain, all because I happened to go to a vegetarian Thanksgiving potluck hosted by a feminist/lesbian artists’ collective in a loft in Lafayette, Indiana, and meet that one hot chick who happened to be studying bacteriophages, whatever they were.

I think the lesson there is to be very careful about accepting invitations to vegetarian Thanksgiving potlucks.

By the way, my forthcoming novel, Mountain of Devils, is a psychological thriller about {a teenage girl who becomes naively enthralled by DNA}, and {the evil-genius Stanford professor of computer science who wants to recruit her into his technopotheistic cult}. It takes place in the 1970s, when the biodigital convergence was just a faint glimmer in some visonaries’ eyes. You’re going to love it. It’s going to scare you to death.

What It Means to Be On Our Own

In reflecting on the experience of researching that Salon essay —pondering the subject deeply, struggling to put my thoughts into words — what struck me was not so much my own perplexities, but the meta-issue of how just like me, many, perhaps most thinking people — including you? — are trying to decode the human genome; trying to figure out what the Human Genome Project called "ELSI"— the ethical, legal, social implications of all this stuff, trying to figure out what this particular aspect of technopotheosis means to us as individuals, societies, and as a species.

As I noodled around the net I came upon various mystically-themed videos by people who claimed to have figured out the true, deeper meaning of “decoding” the human genome, which usually had to do with things like "the God gene" or messages encoded in our DNA by beings on astral planes, or similar pseudo-scientific gobbledy-gook and New Age mumbo-jumbo.

It’s easy to be disdainful of people who believe that kind of gunk, but the phenomenon does point up the larger issue of how people make up their own reality when 'real' reality is inaccessible to them for whatever reason.

Perhaps it’s an inevitable consequence of the notion, which in Western culture arguably goes back to the Reformation, that we don't need 'experts' to explain complicated things to us, we can figure them out ourselves. We don't need priests or professors or scientists, we'll be our own instructors. Especially in the age of the Internet, this notion can be both seductive and positively intoxicating. Depending on where you go from this premise, you can wind up in a democratic place of curiosity, self-empowerment and serious inquiry, or you can end up down a rabbit hole of antivaxx, QAnon or some other, possibly even more rabid land of self-delusion and make-believe.

But how do we know if we're in the land of serious inquiry or down the rabbit hole of magical thinking? This is a subject that confounds me.

A book promo

Sign up for an author’s email list, get a free ebook. This promo includes my illustrated dystopian phantasmagoria The Pains. If you’re already a subscriber to Sundman figures it out!, use that address to claim your book.

What Betty said and a jump rope song

As you'll see if you read that Salon essay, what Betty said, on the subject of genetic engineering, was 'one cheer for the new eugenics'. One cheer being, that is, less than three cheers, even less than two, but nevertheless more than zero. I thought is was a great quip. I don't know how my editor, otherwise a very astute fellow, missed its meaning.

Miss Mary Mack, Mack Mack all dressed in black, black, black with silver buttons, buttons, buttons all down her back, back, back. She asked her mother, mother mother for fifty cents, cents, cents to watch the elephants, elephants, elephants climb over the fence, fence fence.

I didn’t know the Mary Mack song as a kid, but Betty’s and my older daughter, “Jane,” used to do a hand-jive to it with her friend Danielle, and now Jane’s three children do a similar hand jive with each other while reciting Mary Mack.

As to why I decided to include these songs in this post, why, I don’t rightly remember. But they’re entangled with it now, so I’m going to leave them. Perhaps I’ll revisit them some day.

Wild. So wild. We were in the same place 20 years ago and didn’t know it. I think I missed that essay - my Substack notifications got out of whack while I was trying to tune my email volume yet again, so I will have to go read that story.

I was nearly a year into my first job, working as a software engineer at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital in Memphis. I attended with 3 colleagues (including my boss and his), all decades senior to me, so it was a rather interesting trip for a 22-year old. We came in a day early to get cheaper airfare and spent most of the day in the desert gaping a giant saguaros we’d never encountered beyond photos. Somewhere in a box are some photo prints of me standing next to a cactus easily a dozen of me taller than me. I hope I find them one day.

This is the most bonkers thing I've read on Substack so far, and I totally love it! Keep them coming, Mr. Sundman, please. Your mind is like a crazy diamond, shine on!