Preliminary

This essay assumes familiarity with Douglas Hofstadter’s 1979 doorstop Gödel, Escher, Bach: an eternal golden braid (A metaphorical fugue on minds and machines in the spirit of Lewis Carroll) But if you haven’t read that book yet, just follow along. You’re a smart person, you’ll pick up the gist. We will get to Hofstadter, etc, in a minute, but first I’m going to say something about my friend Geoff Arnold.

Geoff Arnold considerations

I first met Geoff in Concord, Massachusetts, sometime in November 1985, at the offices of the new and still quite small East Coast Division of Sun Microsystems — the computer ‘workstation’ company that was rapidly becoming the darling of Silicon Valley in far away California — when I was interviewing for a job as the first and only technical writer for PC-NFS, the implementation of NFS, Sun’s innovative Network File System for personal computers.

Geoff was the chief architect of PC-NFS. Version 1 had not yet been released.

Network File System (NFS) is a distributed file system protocol originally developed by Sun Microsystems (Sun) in 1984, allowing a user on a client computer to access files over a computer network much like local storage is accessed. NFS, like many other protocols, builds on the Open Network Computing Remote Procedure Call (ONC RPC) system. NFS is an open IETF standard defined in a Request for Comments (RFC), allowing anyone to implement the protocol.

If you are not Geoff Arnold you can skip over the next paragraph — although you might not want to, because the name ‘Geoff Arnold’ does come up again in this essay, so reading that paragraph will give you an anchor point for subsequent mentions.

Geoff, because you are so very familiar with most aspects of my long relationship with both the ideas of, and the so-called ‘person’ of, Douglas Hofstadter, you are surely tempted to skip this essay. But now that I have given you such prominent mention you won’t do that, will you?

Rhymes with ‘tedium’

On November 20 of this year I published an essay on the ‘Medium’ website: Gödel Escher Bach, Douglas Hofstadter, and Me. I then made a brief mention of that essay on Facebook, where this exchange with Geoff Arnold subsequently appeared:

Me: My first essay on Medium. Wonder if it'll get any traction. Geoff: Curious why Medium, rather than sticking with Substack? (As for the essay, I'm obviously very familiar with that story.) Me: Simply an experiment to see if I could get any attention — in order to maybe get a few people to check out the substack.

A day or two later I got an email from Medium:

Much of what follows is copy/pasted from that relatively straightforward, and not very attention-getting, Medium essay. As is customary here on Sundman figures it out!, I have souped it up with sundry digressions, allusions, commentary, inquiries, cheap tricks, legerdemain, geegaws, baubles, doo-dads, and ephemeral things.

If you’re one of the 14 people who read that seed essay on Medium, thank you. I won’t be posting there anymore.

GEB, the brain-scrambler

Another recent Medium essay, this one by ‘philosophy geek’ Mark Johnson, Why Gödel, Escher, Bach is the most influential book in my life, caught my attention. That book, commonly referred to as ‘GEB,’ for which Douglas Hofstadter received a Pulitzer Prize in 1980, made a big impression on me too.

I remember the buzz that GEB generated when it came out — glowing reviews in Scientific American and the New York Times Book Review, among others — and I bought a copy as soon as it became available in Von’s Bookstore near the Purdue University campus. I read it with great enthusiasm. I found the ideas in it new and thrilling.

New and thrilling and way over my head. I probably understood about one third of that book my first time through it.

Actually I probably understood less then a third of it on first reading, though in my youthful arrogance I thought I understood it all.

Douglas Hofstadter, human

About a year after leaving Purdue (where, at that vegetarian Thanksgiving pot luck gathering in that loft in Lafayette, I met that molecular biologist with the great figure — as discussed, inter alia, in I Saw a Tangerine Sun Suspended in Haze Over the Cemetery Tonight) I was living in Somerville, MA, near the Tufts campus, with my fiancée, when I saw a notice that Hofstadter was to give a talk called “A Conversation with Einstein’s Brain.” So I went, with a friend of mine, and brought with me a copy of GEB for Hofstadter to sign. The talk, in which Hofstadter imagined Albert Einstein’s brain somehow encoded on a phonographic record, was predictably quirky, thought-provoking, and a bit irreverent. It was fun, as I recall.

During the reception after his talk I told Hofstadter that I intended to give a copy of his book as a wedding present to my wife, and asked him to write something apropos. Which he did.

GEB: brainworm hazard

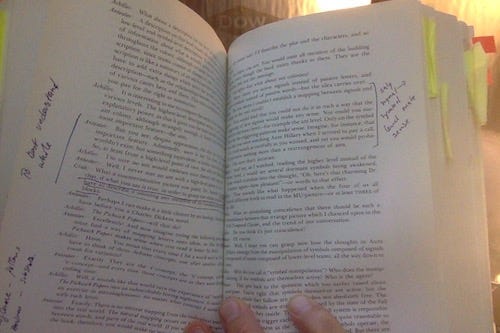

Over the next twenty years I read GEB a couple more times, filling my copy (copies, more correctly) with annotations, placing post-its on seemingly every third page and putting notes on filing cards where they would’t fit on post-its or in margins. Like so many others, I became a GEB obsessive.

The soul of The Soul of a New Machine and me

When I first met Doug Hofstadter at that Tufts lecture in 1980 I was only a few months into my job as a junior technical writer at computer maker Data General, a job I had talked my way into despite having no real qualifications for it. In early 1980 when I got that job my understanding of the principles of computer hardware and software was, to put it mildly, rudimentary.

You of course remember Data General from Tracy Kidder’s epic Pulitzer Prize-winning The Soul of A New Machine, forty-two years old and still the greatest non-fiction book yet written about the thrill of designing a computer’s central processing unit, the CPU. Tom West, the original geek rock star, the Ur-geek rock star, is the central figure in Soul of a New Machine. Tom West, with whom I worked at Data General, is the ‘Tom’ alluded to in my essay What’s the frequency, Tom? which also discusses New Age mystical woo-woo, among other things.

By the year 2002 I had written about twenty hardware and software manuals, had been a manager of a fifty-person information architecture group — half of which was in Silicon Valley, California, with the other half in Massachusetts — and had written and published Acts of the Apostles, a nano-bio-cyberpunk novel about a Silicon Valley evil genius and would-be messiah and the cult of techbros who venerated him.

Which is to say that over the twenty-two years that had passed since my first reading of Gödel, Escher Bach I had acquired a much better foundation for engaging the ideas in it.

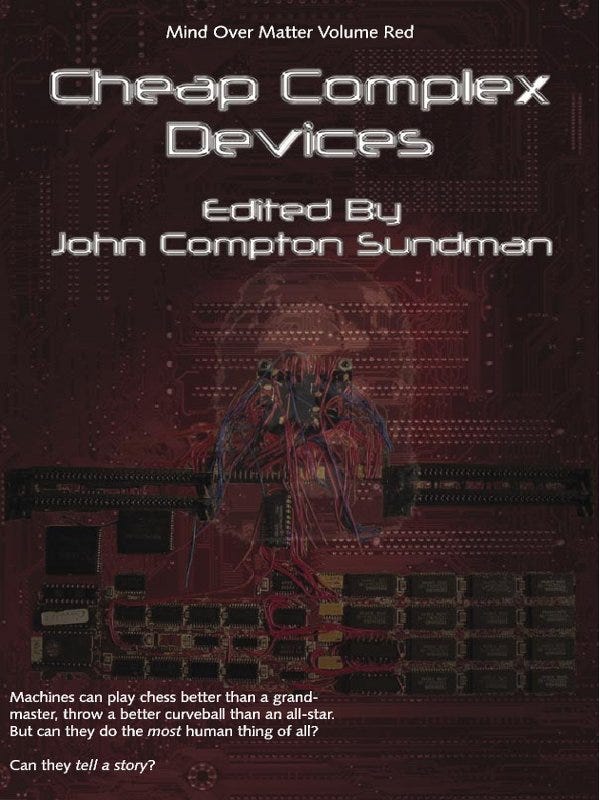

Cheap Complex Devices: an eruption of Hofstadter derangement syndrome

The year 2002 rolled around and I still couldn’t stop thinking about Hofstadter’s book. In particular I kept thinking about the authorship triangle that he had proposed on page 689. In it he imagines three novels such that the author of each one of them only exists in another novel in a series.

The caption reads,

There are three authors — Z, T, and E. Now it so happens that Z exists only in a novel by T. Likewise, T exists only in a novel by E. And strangely, E, too, only exists in a novel — by Z, of course. Now, is such an authorship triangle really possible?

I decided that I would attempt to create just such a triangle. The second book in my series (which I call Mind over Matter (Overmind)) is a novella called Cheap Complex Devices (“CCD”), which purports to be the report of the inaugural Hofstadter Prize for Machine-Written Narrative. In CCD I imagined a novel written by a program like ChatGPT, the subject of which novel is a program like ChatGPT that runs amok as it writes a novel about machine-written narratives.

(This was of course twenty years before LLM/transformative programs like ChatGPT existed.)

Douglas Hofstadter meets Tom West

In writing Cheap Complex Devices I tried, as Hofstadter had done in writing GEB , to be “in the spirit of Lewis Carroll.” I put into my book, in one way or another, everything I knew or sensed or loved or misunderstood about the ideas of Douglass Hofstadter. When I finished writing it, I was happy with what I had written.

So I looked up Hofstadter’s address at Indiana University and mailed him a copy of Cheap Complex Devices, and I sent him an email telling him that I had done so.

A little while later I got a nice reply from him, in which he invited me to call him on the phone to chat. Which I of course did.

(As Acts of the Apostles is the best fictional depiction of the thrill of designing the digital logic of a computer, Cheap Complex Devices, through the character Tom Best —my transparent cipher for Tom West — places you inside such logic. Only, in CCD the logic in which you find yourself is unfortunately full of bugs.)

During that phone call Doug Hofstadter and I talked about all manner of things; I don’t remember the details. But one thing I do recall, clearly, however, is Hofstadter telling me that he was not going to read the little book I had written as a kind of homage to him. He didn’t have the time, he said. Life is short, and there were too many other things he wanted yet to do. My book just wasn’t that important to him.

I replied “Cheap Complex Devices, which I actually wrote for you, Professor Hofstadter, is a very short book! You could have read it in the time you just spent explaining to me that you didn’t have time to read it!”

But he had made up his mind, he was not going to read my book, and that was that.

Hofstadter, Dennett, Salon, AI and a Scared Firefighter up in the Bucket

All of the AI-Hofstadter-related topics discussed above and in the next several paragraphs, and much more, are discussed in my 3-part essay A Scared Firefighter up in the Bucket, which also contains many links. If these topics interest you, you should read it at your earliest convenience.

On the basis of my having written CCD, Salon asked me to write about the history and the then current state of “chatbots,” with a focus on The Loebner Prize, which was to be awarded to the first such bot that could pass a Turing Test. The result was an essay to which my editor gave the unfortunate title ‘Artificial Stupidity’.

During the course of my research for that story I had a few email conversations with Daniel Dennett, a ‘philosopher of consciousness’ based at Tufts who had been an early proponent of the Loebner Contest but later came to repudiate it. He and I talked not just about AI and chatbots, but about the history of the Loebner Contest and how it happened that the academic community that had once embraced Hugh Loebner and his prize later shunned him and denigrated his contest. I found some of Dennett’s arguments unconvincing and even a bit self-serving, and so in my story for Salon I kind of poked fun at him a bit.

I should mention that Dennett was an occasional co-author of Douglas Hofstadter.

A Surprise Mind, Full of Philosophy

Some while after my Salon story came out got a note from Hofstadter inviting me to come to Tufts where he was to give a guest lecture in one of Daniel Dennett’s classes. After the class, Hofstadter wrote, he and Dennett and a few others would be going to dinner, and Hofstadter was inviting me to join them.

Now, although I had chatted with Dennett on the phone and had exchanged a few emails with him I had never actually met him in person. And I had just ridiculed him in an essay that had been read by tens of thousands of people. So I was a bit nervous about meeting him, not to mention that I was nervous enough about going to dinner the legendary Hofstadter. By by ‘a bit nervous,’ I mean so nervous that I had sweated through my shirt by the time I actually walked in to Dennett’s classroom.

But when I walked into that classroom (more than an hour late, just after Hofstadter’s lecture had concluded and the students were filing out; my awkward arrival further adding to my nervous dread), the first person I saw was neither Hofstadter nor Dennett. It was a friend! someone I hadn’t seen in ten years and had no expectation of seeing anywhere — least of all in that classroom, because in my mind he had, like so many of my friends from my years at Sun Micrcosystems, by that time relocated to California or Taiwan or some other exotic locale).

Geoff Arnold, what are you doing here?

Many people find, when they hit the age of fifty-five or so, moving in the direction of finally doing things the’ve been meaning to do for a long time. In my case that that was becoming a firefighter. In Geoff’s case it was pursuing advanced studies in Philosophy of Mind. He jumped out of his seat and came over to greet me as Dennett’s voice boomed out, “Perhaps this is Mr. Sundman now!”

So six or eight of us went to dinner, and it was a blast. When the check came, Dennett said, “I’m paying half of this” and Geoff immediately said “and I’m paying the other half.” Which was a big relief to me since my net worth at that time was about fifteen dollars, and moreover that very afternoon a crown had come off a very prominent front tooth (which of course made me even more self-conscious and nervous) and I knew it was going to cost me more than a thousand bucks to replace it.

Alas I don’t have time or space to write at length here about that epic gathering of mighty minds. Highlights included:

how, at dinner, Hofstadter pulled out a copy of my Salon story, which he had printed out, and read with great glee the portions where I had made fun of Dennett;

how the next day, at MIT, thronged by a gaggle of admirers, Hofstadter spotted me and called out “This is John Sundman. He’s written a great article about AI on Salon. You should go read it;”

and how, when I put another copy of Cheap Complex Devices into Hofstadter’s hands, he said ‘thank you,’ but repeated his intention to not read it.

If you want to read all about how I researched and wrote that Salon article on Hugh Loebner and the state of artificial intelligence in the year 2003, or about that dinner with Hofstadter and Dennett et al, or about how I conceptualized my Mind over Matter trilogy as a Hofstadtertarian authorship triangle, I refer you most emphatically to Scared Firefighter up in the Bucket, where all these things, and also my wife’s porch gardens, the somewhat poignant tale of the last days of the Loebner Prize (more than fifteen years after I wrote about it for Salon), a song by Jefferson Airplane, and the varieties of existential dread occasioned by recent developments in AI — as well as, of course, that scary incident battling the heat and flame of a roaring house fire — are discussed.

Speaking of Pulitzer Prizes and the Bucket of Tisbury 651, my alma mater

Below, a photograph by Tim Johnson of the Vineyard Gazette, of two firefighters applying wet stuff to the hot stuff during firefighting operations at the Hackney family residence on Martha’s Vineyard in 2022.

It was in a similar situation, in that very bucket, (with firefighter Murphy, who I believe is the fellow in the right in the photo, though it’s hard to tell) that I had the momentary experience of terror that I wrote about in my Scared Firefighter up in the Bucket essay.

In my ten years as a firefighter I learned that nearly all interesting fires are sad fires, and the Hackney fire was no exception to that rule.

But that fire was deeply moving for me in another way, for it was at a dinner party at that house, in 2005, that I first met Geraldine Brooks (who was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for fiction for her novel March in 2006), and her husband Tony Horwitz, who was cruelly taken from us by cardiac arrest in 2019, three years before the Hackney home burned to the ground. Tony was awarded the 1995 Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting for his stories about working conditions in low-wage America published in The Wall Street Journal.

I wrote about all that in my Sundman figures it out! essay Every Cosmic Vacuum is Filled with Cosmic Energy.

Hofstadter, GEB. And me?

The Wikipedia page for GEB includes these lines:

By exploring common themes in the lives and works of logician Kurt Gödel, artist M. C. Escher, and composer Johann Sebastian Bach, the book expounds concepts fundamental to mathematics, symmetry, and intelligence. Through short stories, illustrations, and analysis, the book discusses how systems can acquire meaningful context despite being made of “meaningless” elements [. . .]

Gödel, Escher, Bach takes the form of interweaving narratives.

Many essays in Sundman figures it out! begin with a variation on this intro:

At Sundman figures it out! we aspire to the intricate art of consecution.

Themes emerge, interleave, dance around, fade away, and sometimes reappear. Incidents ramify, and their import may change upon being revisited. So reading earlier posts, for example this one, will enhance your experience of reading those that come later.

But if this is your first time with us, then, like William Shatner said, you have to start somewhere, so you might as well start here.

Below, one of my favorite shelfies — photos sent by my readers of one or more of my books on their shelves. Note, on the right of the frame, my Acts of the Apostles taking the place of honor next to a rare black-spined edition of Gödel, Escher, Bach. For this and other fun pictures like it, please see my recent post A Quick Visit to Shelfie City.

Sundman figures it out!, which I should probably subtitle “an autobiographical meditation in the spirit of Lewis Carroll and Douglas Hofstadter,” like GEB, takes the form of interweaving narratives.

Come to think of it, “an autobiographical meditation” would be a fine description for Tony Horwitz’s books Confederates in the Attic, A Voyage Long and Strange, Blue Latitudes, Boom, and Spying on the South. In fact I sometimes find myself trying to channel my inner Tony Horwitz a I write these things. But that’s a topic for another day.

I've owned a couple copies of GEB, but still have yet to finish any of them. (I did finish and LOVE "I am a Strange Loop", though.)

About the time I started getting serious about reading it, I had already made the transition over to electronic readers (how I read "Strange Loop"), and unfortunately, GEB never made that transition over. There is nominally an electronic copy floating about, but it's a shoddy PDF that's hardly legible on any of my reading devices.

Wow! That was an intense read! Loved every sentence, felt every word, emotion with you. Thank you so much for sharing, John. Unfortunately, I haven’t read GEB, I’m sorry to say I don’t remember if I’ve heard of it or not. I do have most of the paperbacks in that shelfie, huge fan of Kafka, and philosophy and psychoanalysis too.

I thought of looking for an ebook of GEB, but read above Chris J. Karr’s message how difficult it is to find it. I’ll try though, even get the PDF as a last resort. But first I will read your Act of Disciples, of course! That goes without saying. lol.

Once again, thank you, John. It was a pleasure to read your article.

Have a lovely week.