I begin writing this entry at 10:47 on a Saturday morning. Just about exactly one week ago to the minute I got a phone call from my friend Susan. She and my wife Betty had taken Susan’s dog Dundee and our dog Spot for a walk. Spot and Dundee tend to cavort with great enthusiasm on such excursions, and so it came to pass, Susan told me, that Spot, in her joyous sport and frolic, had knocked Betty over, and now Betty could not get up. Could I please come help?

So I got to where they were and made my expert analysis of the situation and called for an ambulance forthwith, which promptly arrived, staffed with people I recognized but didn’t really know: when I exercise in the weight room in the loft that overlooks the apparatus bay at the Tisbury Emergency Services building I often see EMTs below, whether going on a call or cross-checking the ambulances during a change of shift, or merely hanging out. I recognize them, we say hello to each other, but I don’t really know them.

Oh yeah, one of the young EMTs said, as she was gathering info and noticed my TFD t-shirt. I knew I recognized you from somewhere. You work out upstairs. You’re a firefighter. Replied I, I used to be — and they rigged Betty up with an IV and gave her some pain medication & drove her to Martha’s Vineyard Hospital where inconclusive X-rays were taken followed by a CT scan which conclusively showed a broken hip, and, long story medium-short, 5 hours after the assault she was on a helicopter to Brigham & Women’s Hospital in Boston, and I was in our car on the ferry, having taken twenty minutes to pack a few things and assemble some cash.

Nor was this Betty’s first flight on a flying ambulance from Martha’s Vineyard to Boston: on the day we learned that Tr**p had been elected President, Betty had suffered a massive pulmonary embolism, and, thank Fred, she had collapsed in a public place where some citizens had seen her, and called 911. On that occasion also I had followed by automobile on ferry and highway, after gathering some necessities, including cash.

Hip replacement surgery occurred on Monday. I spent most of Sunday through Thursday hanging out with Betty in her hospital room or, at night, crashing on a couch at my friend Gary’s house in Arlington. I also squeezed in a quick trip back to the Vineyard to deal with Spot and one or two other things. During this time I tried to work on my John Sundman: Famous Author project, but without much success.

Thursday morning, a few days after her surgery, Betty was cleared to be transferred by ambulance to Spaulding Rehabilitation Hospital on Cape Cod, a place with which I’m well familiar. As Betty headed for Spaulding I headed for home, with a reservation on the 1:15 ferry out of Woods Hole.

I drove onto the boat for the 45 minute ride to the Vineyard, put the seat back, pulled the brim of my cap down over my face & closed my eyes, composing a Sundman figures it out! post in my head. It had been an exhausting and worry-filled few days and I was looking forward to getting back home, being in my own house, sleeping in my own bed instead of on my friend Gary’s couch. I had just dozed off when my cell buzzed.

All of your attention are belong to us

Seems that my 40 year old son Jake had just had a very nasty seizure and was being taken to Martha’s Vineyard Hospital. (I am Jakob’s health care proxy and chief advocate.) I arrived at the hospital only a few minutes after the ambulance did, and when I was allowed to go into the E.R. I found Jake in Room 5, same room in which Betty and I had hung out a few days earlier while waiting for remote radiologists to read the images of her poor hip, after which reading a helicopter was called for. Jakob was in a postictal haze but already coming around.

Over the years I’ve seen Jakob have several dozens of seizures, starting from the very first time when he was about a year and a half old, sitting there in his diaper in the middle of kitchen floor in our house in Gardner, Massachusetts, shaking like a skeleton in a Looney Tune. I am a connoisseur of his post-ictal states. I know the signs that tell whether Jakob is (a) in the clear or (b) in danger and likely to seize again. All the signs looked good, so I wasn’t worried about him slipping back into another seizure. But I had another concern: what had brought this one on?

In general, Jakob’s seizures are caused by one of four things:

medications being out of whack;

emotional stress;

certain noises, including vacuum cleaners;

capricious pranks by one of the lesser gods on Mt. Olympus.

The details needn’t concern you, but the point is, the question of what had caused this seizure preoccupied me as I sat in the driver’s seat of my Subaru en route from Woods Hole, America, en route to Martha’s Vineyard.

So anyway that required intellectual and emotional effort, which effort kind of, you know, as Beatrix Potter might have said, disturbed the dignity and repose of the mental tea party I had been envisioning for myself as I pulled the brim of the cap to shut out the harsh fluorescent light on the freight deck of the ferry before that phone call roused me from my slumber.

The Sundman figures it out! post which I had been composing in my head disintegrated.

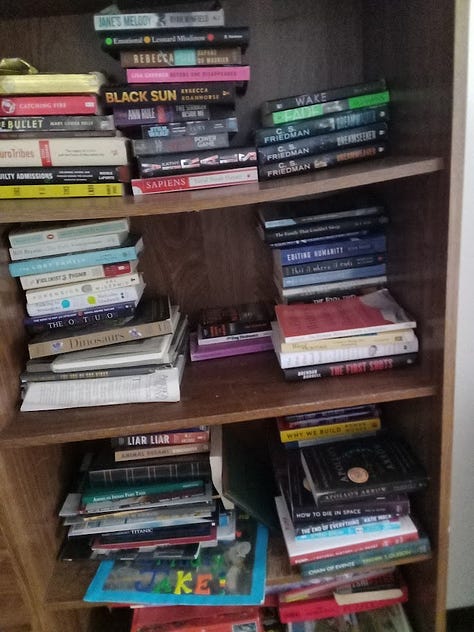

The ferry arrived in Vineyard Haven, I drove off the boat and straight to Martha’s Vineyard hospital, 1 mile away from Steamship Authority terminal. I spoke with the medicos; Jake was out of danger, he was discharged. I helped him gather up the thirty or so pounds of books he had had with him at the time of his seizure, and I got him to his apartment & made sure all was well there.

Then I drove the 1/4 mile from Jakob’s apartment to my house and had a beer and noodled around on Twitter, having abandoned all hope of doing anything productive in a writerly way on that day.

Betty, meanwhile, had arrived at Spaulding after a nearly three hour ambulance ride, half of that time in stop-and-go traffic in Boston. When she called, we of course talked about Jakob’s seizure, a perennial subject of John & Betty conversations these past 38 years.

Sundman figures it out! and the ancient art of weaving

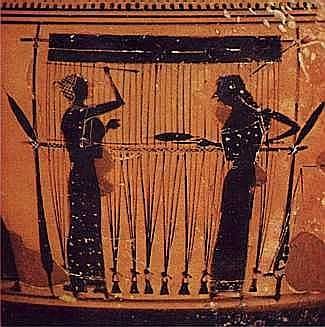

Keith Richards likens the interplay between the various guitar parts on Rolling Stones songs to what he calls ‘the ancient art of weaving’. I suppose that’s an apt description of all kinds of music, but listening to Stones songs in particular I sometimes conjure a mental image of two people working together on an old-fashioned loom, passing the shuttle back and forth.

Think, for example, of the trade-offs between the Mick Taylor and Keith Richards parts in Sympathy for the Devil on the 1970 live album Get Yer Ya-Ya’s Out! While one plays a solo, the other vamps the chords. I think of those chords as the warp of the song, the longitudinal threads of the fabric, and the solos as the weft, the crosswise threads.

In ‘Sympathy,’ on Ya-Yas, Richards’ solo is first. His Telecaster is snarling, insistent, a weapon of blunt force. Richards beats you over the head with it. Then we hear the musical shuttle pass effortlessly from Richard’s Telecaster to Taylor’s lyrical, melodic, almost playful Les Paul. It’s a perfect handoff, like Talitha Diggs passing the baton to Abbey Steiner. (No these analogies are not perfect, and yes, I’m mixing metaphors. Sue me.)

Anyway we’re not here to talk about the Rolling Stones or the women’s 4 x 400-meter relay in the 2022 World Athletics Championship in Eugene, Oregon, are we? No, we’re not. We’re here to talk about this here substack, which today is renamed Sundman Figures it out!

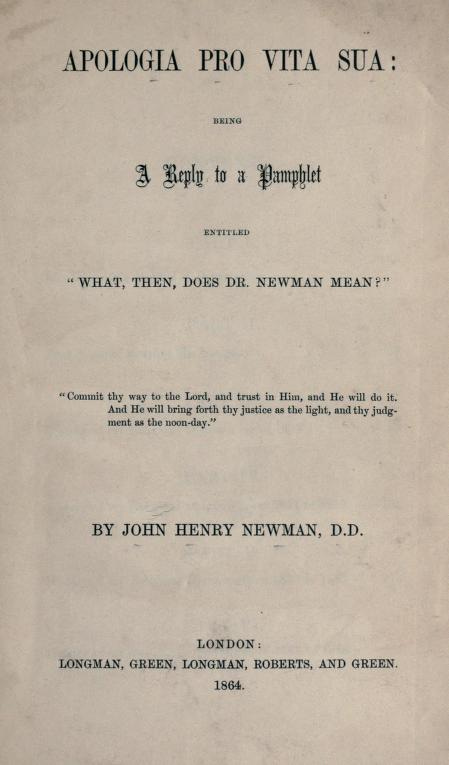

So hold that thought about weaving, we’ll come back to it after a short detour to visit John Henry Newman’s spiritual autobiography, Apologia Pro Vita Sua:

I’m sure you remember from your Jesuitical studies that Newman’s Apologia for his life is not an apology apology, in the sense of I’m so sorry, baby, I’ll never cheat on you again, but a defense — an explanation, a guide to his thinking, a catalogue raisonné of his pensées, a reconstruction of how he became the man he became, and why he felt justified in that becoming.

It occurred to me that Thursday night, thinking about my wife in that ambulance to Cape Cod that day, thinking about Jakob’s seizures, that there are so many things that shape each of us that we hold only unto ourselves (or maybe, if we’re lucky, with one or another intimate friend). And these experiences, and the way we think about them consciously are not are like the warp and weft of who we become.

Yeah, wow, you say, what a profound insight, John, that our experiences shape who we become. I realize that this is not a ground-breaking insight like Hamilton’s quaterions, worthy of being carved into rock with a penknife, but what I’m trying to get at is the rhythmic, periodic, musical aspect to all this. Those episodes in our lives that have a kind of talismanic power that persists, that come back again and again, like theme in a Beethoven quartet or a riff in a Stones song — despite, sometimes, being seemingly unremarkable when they occurred.

So let me tell you what I’m going to attempt to do with this Sundman Figures It Out thing. Like Newman, I’m going to weave a story out of the various threads of my personal history — from the little farm where I grew up to Africa to Silicon Valley and Martha’s Vineyard and all kinds of other places; high tech, lo tech, everything in between; medical emergencies & intellectual adventures, personal relations & responsibilities, preoccupations, coincidences, portents, signs & wonders & so on and so forth, in a way that will reward you for reading every issue. Sundman Figures It Out! is going to be more like a novel or TV serial than a miscellany of “this thing happened” and “that that thing happened:” Like The Mighty Mighty Bosstones, with each post I’ll try to move the song along and tries to find the plot.

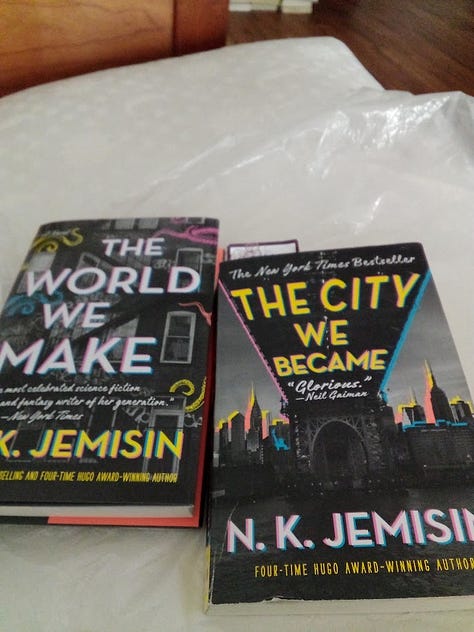

I hope that this will make the reading more interesting for you, and it will certainly make the writing more interesting for me. The whole point of this substack exercise, after all, is to get you hooked on my stories so you’ll buy my damn books. I do love yo and all, but this is a mercenary enterprise. Or if not mercenary at least mercantile. And a bit terrifying, actually.

Because in truth although I have a hundred stories to tell I don’t know how I’m going to weave them all together in a way that will snare you; I don’t know if I’m going to be able to grow this list to thousands of subscribers, I don’t know how I’m going to convince several thousands of people to buy my books, which is something I urgently need to do. I’m just going to have to figure that out. With the words of Bob Seger’s Against the wind, in my head

Well those drifter days are past me now

I've got so much more to think about

Deadlines and commitments

What to leave in, what to leave out

So there you go, now you know

I’m putting down my marker. Every Sundman figures it out! post from now on is going to build on the ones before it. This is going to cohere and reward close reading. I don’t expect writing it to be easy. But as Jimmy Dugan said, if it were easy everyone would do it.

Here’s a photo I found one day in my twitter feed. It was taken by a person with a few hundred followers —I remember their name but not their age or gender or how I came to be following them. They said they had been driving through somewhere in Iowa, as I recall, and saw this building and found it interesting enough to stop their car and snap a picture of it.

Here’s part of the ‘alt’ text I wrote for this picture.

Top 1/2: A small, white, forlorn, symmetrical 1-story building. Two concrete steps lead from sidewalk to front door. On either side of the door, shaded by a dented corrugated awning, are matched picture windows. Centered under each window is a bench. 4 slender poles hold up the awning. Mounted above the building, centered, a white rectangular sign. Faded pink letters form 2 words: EASY WAS. Above & around the building: bright blue sky. Above the word 'WAS,' smaller, in faded blue letters, "Coin operated". Below: "Lau dry". Those words, & a leafless tree leaning from the left, are the only things that break the symmetry.

Feeling: mystery, loneliness, dashed dreams

I am intensely drawn to this photo, and to images like it. I don’t know why that is. I’m not a morose person. I’m not lonely (though I am introverted, happy enough in my own company). Maybe I find things like this compelling because like, I suppose, everybody, I’ve been lonely, I’ve seen some of my dreams go up in smoke, I’ve failed on enterprises as modest as this small coin-operated laundromat.

So what is going on in this photo? What is it trying to tell me? Maybe it’s something about what seemed easy, what was supposed to be easy, wasn’t in fact, easy? That ‘easy’ never was?

These are the kinds of things I’m going to try to figure out.

Here’s what John Henry Newman had to say about his his own figure it out project. It’s 2:24PM on Sunday. I close with them.

For who can know himself, and the multitude of subtle influences which act upon him? And who can recollect, at the distance of twenty-five years, all that he once knew about his thoughts and his deeds, and that, during a portion of his life, when, even at the time his observation, whether of himself or of the external world, was less than before or after, by very reason of the perplexity and dismay which weighed upon him,—when, in spite of the light given to him according to his need amid his darkness, yet a darkness it emphatically was? And who can suddenly gird himself to a new and anxious undertaking, which he might be able indeed to perform well, were full and calm leisure allowed him to look through every thing that he had written, whether in published works or private letters? yet again, granting that calm contemplation of the past, in itself so desirable, who can afford to be leisurely and deliberate, while he practises on himself a cruel operation, the ripping up of old griefs, and the venturing again upon the ‘infandum dolorem’ of years, in which the stars of this lower heaven were one by one going out?